“I am the ghost of everything we lost. I speak, but no one hears. I close my eyes when I look out windows. The hollow rat-tat of guns echoes between empty buildings, trees grow between the stones, breaking a city already broken. The wild dogs starve.”—Marianna

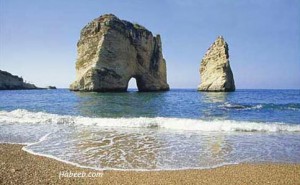

Told by Marianna, a young woman who has lost all sense of “home” as a result of the more than ten years of warfare she lived through in her homeland of Lebanon, this impressionistic psychological novel begins with her dreams of “before the war was real.” Romantic images of her mother “wander[ing] outside, smelling the ghostly jasmine in the dark, and Daddy open[ing] another old book under a lamp” overlap with images of her grandparents lighting the candles on a Christmas tree while sweet wine boils on the stove. Marianna herself often picked thyme with a young friend, visited ancient sites with her family, walked along the seashore in Beirut, and shopped in the souks. Summers were special, as the family vacationed in the countryside, where they harvested lavender, picked figs, and enjoyed the terraces that ran through fields filled with poppies, daisies, and heather.

Told by Marianna, a young woman who has lost all sense of “home” as a result of the more than ten years of warfare she lived through in her homeland of Lebanon, this impressionistic psychological novel begins with her dreams of “before the war was real.” Romantic images of her mother “wander[ing] outside, smelling the ghostly jasmine in the dark, and Daddy open[ing] another old book under a lamp” overlap with images of her grandparents lighting the candles on a Christmas tree while sweet wine boils on the stove. Marianna herself often picked thyme with a young friend, visited ancient sites with her family, walked along the seashore in Beirut, and shopped in the souks. Summers were special, as the family vacationed in the countryside, where they harvested lavender, picked figs, and enjoyed the terraces that ran through fields filled with poppies, daisies, and heather.

Now the war is “real,” however. Years have passed, and the old reality she yearns for remains only in her dreams. Marianna, now eighteen, is in another place, America, her father’s birthplace, where, she believes, “nothing can be beautiful” and where she looks “inward to the night, to my dream self who had promised that this time I really had gone back home to my true life.” The warfare she experienced in Lebanon, which began in 1975-76, when she was seven, is now thousands of miles away, but she has been unable to cope with a new life in the US. A recent hospitalization has made her body stronger, but it has had little effect on her psyche, serving primarily to make her family aware of the fact that she must be watched constantly.

Focusing almost exclusively on the four people in this family, on their friends, on those who died in the war (between 1975 and 1990), and on Lebanon itself, author Patricia Sarrafian Ward recreates the psychological damage which the war in Lebanon has created for this family. Herself an exile who arrived in the US from Lebanon at the age of eighteen, the author provides vivid images of Marianna, the speaker, trying to cope, first, with her older sister Alaine’s dramatic and emotional escapes from the war and then with her own traumas as both Alaine and Marianna lose their way psychologically, the very underpinnings of their lives destroyed. Neither parent seems to know what to do with their troubled daughters, hoping, apparently, that time and family love will effect cures. Their father, an American academic, is somewhat distant, and their ineffective though loving mother, part Armenian (her family having escaped the genocide in their own homeland) has always felt a bit different.

Through flashbacks their lives in Lebanon unfold. Alaine, the older daughter, picks up bullets, shrapnel, and the other detritus of war, including a gas mask and canteen from a dead Syrian soldier, creating a collection of memorabilia in her room. She sneaks out at night, runs away periodically, and becomes sexually precocious. She cuts herself. Marianna, sometimes assigned to watch her older sister so she will not run away, seems to have a greater sense of stability, but she, too, eventually shows some of the same signs, as “the awful weight of everything I do not understand about the world sank into me.” Other friends and members of the family also exhibit signs of trauma, one son determined to avenge the death of his father, an old woman running away from the protection of their house because she fears the family will abandon her, people making up stories to hide real causes of death, Marianna’s family refusing to leave when they have the chance to do so. As Marianna herself says, for her the war was “other people’s business.” Eventually, however, “The world grew smaller, until there was only my room.”

Some of the specifics of the war do intrude briefly into the narrative, though the focus is almost exclusively on this family, and as the time frame moves back and forth, and even slips into dreams and fantasies, it is often difficult to establish a historical chronology of the war. At the outset, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have formed militias, the PLO is established, and guerrillas attack. Eventually, Syria invades, Israel bombs Beirut to combat the Palestinians, a multinational force (of the US, France, Britain, and Italy) tries to establish some sort of order, and a suicide attack against the US and French headquarters leads to the deaths of three hundred US and French soldiers. Sunni Muslims and Shi’ias have their own militias, the Socialist Druze sect allies itself with the Soviet Union, Christian militias try to protect the long Christian traditions of the country (which the Syrians oppose), and the civilian population is squeezed by all.

Patricia Sarrafian Ward writes a dramatic and harrowing story of Marianna and her sister, one of whom (Alaine) acts out her problems primarily while the family is in Lebanon, and one of whom (Marianna) does so primarily after they emigrate to the US. Their destroyed concept of “home” underlies their problems, and it is not, of course, until each is able to see new possibilities for their lives that any reconciliation can take place. The story, though complex in its time frame, is relatively simple in its prose style, with lovely lyrical descriptions of nature and the changing seasons alternating with short, sometimes abrupt, sentences propelling the action along as Marianna tries to process what is happening in her world. The novel is somewhat monochromatic, however, with Alaine and Marianna representing the primary focus, and there were times that I longed for a moment of humor or change in tone. The girls’ lack of overall perspective on the action, due to their youth, may be partly responsible for this, and it may also explain the depiction of their parents as seemingly ineffective and even indifferent as the crises evolve. A few signs of hope arise in the conclusion, leaving the reader to hope that the novel is not as autobiographical as it sometimes feels.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.citypages.com.

At this point, I introduce a photographic website from which I have taken all the remaining photos of Lebanon. It’s an extraordinary website with 86 separate pages and hundreds of photos, both recent and historical, and I encourage everyone who reads this review to take a look at it. It shows more about Lebanon than any other site I have found. I have not been able to find a way to contact the website owner, but I hope he will see this and contact me via my Facebook page as described in the About page (see tab at top of this page), so I can thank him. http://www.habeeb.com

Pigeon Rock along the Beirut waterfront is here: http://www.habeeb.com/lebanon.photos.17.beirut.html

The red-roofed houses in the Lebanon countryside appear here: http://www.habeeb.com/lebanon.photos.01.lebanese.homes.houses.html

A family escaping the bomb damage. The man in front is wearing only flip-flop sandals on his feet. See: http://www.habeeb.com/lebanon.photos.45.html

For me, this iconic photo of an old man with a suitcase sums up this war and all other wars. http://www.habeeb.com/lebanon.photos.44.html

The map is from http://articlesofinterest-kelley.blogspot.com

An interview with the author is here: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/azad-hye/message/437