“Our neighbors collaborated with [the Israelis] when they took our country in 1948. Our stinking feudal system allowed for that. Then our Arab brothers assisted (although they say that they countered, no, worse, that they fought against) in the takeover of our lands in 1967, and since then we have missed opportunity after opportunity. Pusillanimous diplomacy. Corrupt leadership…No ability to work together, to fight together…It [is] one long history of betrayal. They screw us; we betray ourselves.”

In her debut novel, Out of It, British Palestinian author Selma Dabbagh creates a family from Gaza which reflects all the stresses, conflicts, and competing philosophies endemic to that world, a small strip of land along the Mediterranean coast in the westernmost corner of Israel, bordering Egypt. Main character Rashid Mujahed, the second son of his family, lives with his mother, twin sister Iman, and older brother Sabri, and though the family is well enough off to be able to travel abroad, they are firmly linked to Gaza, their home, at least for now. From a satellite Gaza looks like a “bonery…dried out coral, ridged, chambered, and sandy,” Rashid observes, while the other side, the Israeli side, “the place they came from, that had been theirs, the one they weren’t allowed to even visit anymore, it wasn’t bones, but a blanket: an elaborate blanket of modernist design…That side glinted.” Rashid has applied to attend graduate school in England, with the aid of Lisa, his activist girlfriend from London, and despite the frantic activity going on around him in Gaza, with many political movements arising and competing with each other, he despairs of much change.

In her debut novel, Out of It, British Palestinian author Selma Dabbagh creates a family from Gaza which reflects all the stresses, conflicts, and competing philosophies endemic to that world, a small strip of land along the Mediterranean coast in the westernmost corner of Israel, bordering Egypt. Main character Rashid Mujahed, the second son of his family, lives with his mother, twin sister Iman, and older brother Sabri, and though the family is well enough off to be able to travel abroad, they are firmly linked to Gaza, their home, at least for now. From a satellite Gaza looks like a “bonery…dried out coral, ridged, chambered, and sandy,” Rashid observes, while the other side, the Israeli side, “the place they came from, that had been theirs, the one they weren’t allowed to even visit anymore, it wasn’t bones, but a blanket: an elaborate blanket of modernist design…That side glinted.” Rashid has applied to attend graduate school in England, with the aid of Lisa, his activist girlfriend from London, and despite the frantic activity going on around him in Gaza, with many political movements arising and competing with each other, he despairs of much change.

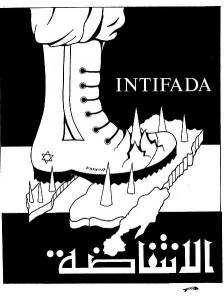

Sabri, Rashid’s older brother, lost both legs fifteen years ago in an explosion which killed his Christian wife and his son during the First Intifadah, and he now spends his time documenting the never-ending attacks on Gaza and chronicling the horrors he observes from his wheelchair at the second floor window of his house – a recent bombing of the hospital in Gaza following the suicide bombing of an Israeli park by the Islamic Justice Party; the killing of children; and all the events of the First and Second Intifadahs. Also living at home is Rashid’s twin sister Iman, a quiet teacher who has studied in Switzerland. While she has no interest in taking dramatic action against Israel, she dislikes the idea of doing nothing, preferring that the country’s leaders take small steps toward solving their problems. Eventually, she falls in with a female friend who offers her an opportunity to do something important politically, only to panic when she finds herself very close to an explosion that kills an important member of the PLO Patriotic Guard.

Their father Jibril, once active in the Palestine Liberation Organization, has escaped to one of the Gulf countries, where he now lives with Suzy, a trophy wife who is the consummate shopper. Back in Gaza, managing the house and family, the mother of the family seems like a fairly “ordinary” housewife, but she has secrets, kept even from her own family, and she does have a strong political point of view, deriding a recent suicide bombing, “To go and bomb a park? What’s the point of that, I ask you? The sympathy our enemy will get for that one…We must stick to military targets…The only person [the bomber] killed was herself…The twit.”

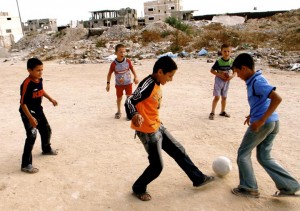

As the well-differentiated family members live their lives and join friends in numerous activities, both political and otherwise, the reader learns about life in Gaza and the various factions complicating any unified action by the Palestinian “government.” As the Israelis seal the borders and begin to demolish houses in the south, demonstrations occur, and some foreigners even arrive to protest, but they accomplish little. The minute the demonstrators leave, additional houses are demolished – a failed attempt to resist, just like their earlier failed boycott of Israeli goods throughout the Occupied Territories. One of Rashid’s friends who runs a refugee Centre, tries to document human rights violations and violations of the  Conventions, but he is foiled on two levels. A close neighbor is arrested for having been a spy for the Israelis for many years, and a friend of Rashid goes missing. As Sabri complains, “My thesis [is] that the Occupation, the closures, the siege have made amputees of all of us, crawling around in the mud. Legless in Gaza. The lot of us.”

Conventions, but he is foiled on two levels. A close neighbor is arrested for having been a spy for the Israelis for many years, and a friend of Rashid goes missing. As Sabri complains, “My thesis [is] that the Occupation, the closures, the siege have made amputees of all of us, crawling around in the mud. Legless in Gaza. The lot of us.”

However interesting and important Part I in Gaza is, the novel seems to be going in many different directions in this section, and it becomes difficult to keep track of who is a member of which party or faction, especially when the characters move in and out of various groups, a confusion which may parallel that of Gaza itself. Part II, set in London, becomes much livelier and even satiric. Rashid is attending university and working with a British researcher who was once a police officer in Palestine during the war. His dinner meeting with girlfriend Lisa’s family and a description of the behavior of a man assigned to the British Foreign Office provide bits of dark humor as they illuminate cultural differences, and this tone continues when, in Part III, Iman arrives in one of the Gulf states to live with her father and the acquisitive Suzy. Additional information on the disasters befalling Gaza comes to them through British newspapers when, in Part IV, Iman arrives in London in Part IV to meet up with Rashid. There they unearth their mother’s secrets and show the cyclical nature of resistance. The novel comes full circle with their return to Gaza months later, and the conclusion forms a well drawn coda to the complicated Gaza setting.

By showing the action through members of a single family with differing points of view, the author makes many issues come alive in new ways and shows how they affect family dynamics. And though the issues and the different political factions attempting to deal with them are sometimes a bit muddled for those of us who are not already familiar with all the various groups in Gaza, Dabbagh’s focus is clearly on those issues. We come to know the characters within the limits of their points of view, and they and their fates become part of the message rather than ends in themselves. The novel is enlightening and often entertaining, descriptive and often memorable, and exciting but often horrific, with few hints that any real solution is forthcoming.

By showing the action through members of a single family with differing points of view, the author makes many issues come alive in new ways and shows how they affect family dynamics. And though the issues and the different political factions attempting to deal with them are sometimes a bit muddled for those of us who are not already familiar with all the various groups in Gaza, Dabbagh’s focus is clearly on those issues. We come to know the characters within the limits of their points of view, and they and their fates become part of the message rather than ends in themselves. The novel is enlightening and often entertaining, descriptive and often memorable, and exciting but often horrific, with few hints that any real solution is forthcoming.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Syed Hamad Ali appears on http://gulfnews.com

The map of Israel, with Gaza and the West Bank, is from http://news.bbc.co.uk

Palestinian children play soccer outside the Rafah Camp in this photo from http://www.rafahtoday.org

The poster of the Intifada of 1990, showing Gaza on the left and the West Bank on the right, was designed by Ayman Bardaweel and appears on http://en.wikipedia.org

ARC: Bloomsbury