“I didn’t want just to translate my family’s experience, a Cambodian experience, to a foreign audience; I wanted to take [my] readers and replant them in the fertile ground I’d sprung from, to let them take root and sprout, and to see my world as their own. I wanted them to see Cambodia before it became synonymous with genocide, before it became the ‘killing fields’… [And] I wanted [also] to articulate something more universal, more indicative of the human experience—our struggle to hang onto life, our desire to live, even in the most awful circumstances.”—from “A Conversation with Vaddey Ratner”

In this autobiographical novel, author Vaddey Ratner has accomplished what every novelist hopes for – she has created a main character and family so vibrant that every reader will truly feel “replanted” and rooted in a different place – Cambodia – where s/he then shares every aspect of the characters’ lives and hopes for the future. Telling the story is Raami, an engaging seven-year-old child of a large and loving Phnom Penh family, which also includes her nanny, cook, and beloved gardener. Together they inhabit a lush, lovely, and endlessly fascinating natural world which offers constant visual surprises and inspires the stories, tales, and poems Raami relates here. Many of these poems and stories have been written by her father, a man she adores, and they infuse her whole life with the magic and beauty of words, offering hope and inspiration even through the atrocities she eventually witnesses.

In this autobiographical novel, author Vaddey Ratner has accomplished what every novelist hopes for – she has created a main character and family so vibrant that every reader will truly feel “replanted” and rooted in a different place – Cambodia – where s/he then shares every aspect of the characters’ lives and hopes for the future. Telling the story is Raami, an engaging seven-year-old child of a large and loving Phnom Penh family, which also includes her nanny, cook, and beloved gardener. Together they inhabit a lush, lovely, and endlessly fascinating natural world which offers constant visual surprises and inspires the stories, tales, and poems Raami relates here. Many of these poems and stories have been written by her father, a man she adores, and they infuse her whole life with the magic and beauty of words, offering hope and inspiration even through the atrocities she eventually witnesses.

Raami’s insights and observations – ingenuous, intelligent, and honest – reflect a kind of reality almost non-existent among other child narrators, and bring the characters within her family to life. Her much younger sister, who enjoys playing with jewelry, is described as “not a child…She was a night bazaar.” Her grandmother (Grandmother Queen) is “blissfully ensconced in old age and dementia.” The hefty family cook, who inexplicably vanishes, eventually “materializes” among a group of butterflies, where she is, to Raami, the “rainbow-colored moth, ” and an elderly couple looks like “old trees that walk and talk.” Her loving father tells her that “In you I see all of my dreams,” and reminds her that “I want you always to believe that the tiniest glimpse of beauty here and there is a reflection of the gods’ abode. It is real, Raami…You have only to envision it, to dare to dream it. It is within you, within all of us.”

Raami’s insights and observations – ingenuous, intelligent, and honest – reflect a kind of reality almost non-existent among other child narrators, and bring the characters within her family to life. Her much younger sister, who enjoys playing with jewelry, is described as “not a child…She was a night bazaar.” Her grandmother (Grandmother Queen) is “blissfully ensconced in old age and dementia.” The hefty family cook, who inexplicably vanishes, eventually “materializes” among a group of butterflies, where she is, to Raami, the “rainbow-colored moth, ” and an elderly couple looks like “old trees that walk and talk.” Her loving father tells her that “In you I see all of my dreams,” and reminds her that “I want you always to believe that the tiniest glimpse of beauty here and there is a reflection of the gods’ abode. It is real, Raami…You have only to envision it, to dare to dream it. It is within you, within all of us.”

Grand Palace, Phnom Penh

Raami’s family, like the author’s, is descended from royalty, and her father is celebrated in the community for his poetry, his devotion to the culture, and his kindness. When the Khmer Rouge take over Phnom Penh, he is, not, at first, very worried. He has always disliked the privileges bestowed upon the royals simply because of their birth, and he hopes that the Khmer will institute democracy. When it becomes obvious that this is not going to happen, her father also realizes that the Khmer will first arrest the country’s wealthy and the educated – diplomats, doctors, police and military officers. Removing this group will remove the challenges they represent to the imposition of Khmer rule, so he gathers the family to flee. He knows he will be a primary target because of his connection to the throne, but he works to protect his family and those who are escaping Phnom Penh with them. Anyone who can read becomes suspect, and people quickly learn to break their eyeglasses and bury them, since they are a signal that their wearers are educated. Her mother pretends to be a servant, and Raami pretends she can neither read nor write.

The family stops at a floating village, built on stilts.

Directed by revolutionary officers and moved from village to village at the whim of the Khmer, the family performs menial labor as they try to hide their background, at one point helping to build an enormous dirt embankment along a river to prevent flooding during monsoons. Food is almost non-existent, and people eat insects and small fish, if they can find them. Babies die because mothers are too emaciated to supply milk, and disease is rampant. Only the revolutionaries have rice, and in their ignorance about farming methods, they demand that their workers, many of whom are farmers who are familiar with the most effective methods of planting and harvesting rice, perform work that is completely contrary to nature, thereby ensuring crop failure and greater starvation. Families are separated as a way to create uncertainty and dependence on the Organization, and Raami sees executions, deaths by illness, and suicides.

Still, even under these circumstances, Raami remembers the stories from her father, looks for signs of new life in nature as he has taught her, and refuses to give in. She knows that as long as she has some kind of hope, it may be possible for her to survive. Working all day long as a human scarecrow, forced to wave her arms constantly to keep crows from eating the rice, she does what she is told, even as her mother is digging rocks to shore up the flood control embankments. It is not until the Vietnamese begin to attack the Khmer, that many revolutionaries in rural areas abandon their positions, and some signs of hope arise for Raami and those in her camp. Eventually, some in the camp take advantage of the lack of organization and head west for Thailand.

Still, even under these circumstances, Raami remembers the stories from her father, looks for signs of new life in nature as he has taught her, and refuses to give in. She knows that as long as she has some kind of hope, it may be possible for her to survive. Working all day long as a human scarecrow, forced to wave her arms constantly to keep crows from eating the rice, she does what she is told, even as her mother is digging rocks to shore up the flood control embankments. It is not until the Vietnamese begin to attack the Khmer, that many revolutionaries in rural areas abandon their positions, and some signs of hope arise for Raami and those in her camp. Eventually, some in the camp take advantage of the lack of organization and head west for Thailand.

Presenting her own autobiography as a novel so that she can compress and condense many of the events that occur between 1975 and 1979, while also combining several real characters into composites, the author says in her “Conversation” at the end of the novel, that Raami’s experience parallels her own. “There’s not an ordeal she faces that I myself didn’t confront in one way or another,” and though there are minor details which differ from reality, Vaddey Ratner, like Raami, “always had faith in people,” a faith which allowed her to survive war-time horrors for four terrifying years and become stronger in the process.

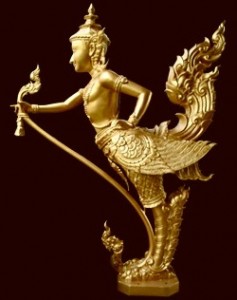

Kinnara

Ultimately, Ratner’s alterego Raami imagines herself flying, her spirit connecting with the past, present, and future. “I could leap into words and stories, cut across time and space. Like Papa, I [became] a kind of Kinnara, that half-bird creature, escaping from this world to another. I could transform myself. I could transcend boundaries.” In this novel Vaddey/Raami does indeed transcend boundaries. “Honor[ing] the lives lost…by transform[ing] suffering into art,” Vaddey Ratner succeeds magnificently, bringing to life those universal qualities that enable strong people to survive even the most horrific circumstances, regardless of time or place.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.simonnovels.com

The National Palace is from http://www.goway.com

The floating village photo was taken on a photo tour: http://mmphototours.wordpress.com

The map of Cambodia and surrounding countries appears on http://blogs.cornell.edu

The Kinnara is seen on http://www.siamtaksin.com

A video interview with the author follows:

ARC: Simon and Schuster