“We’re no longer in a battle with a gang of criminals, this time it’s a government and department.”

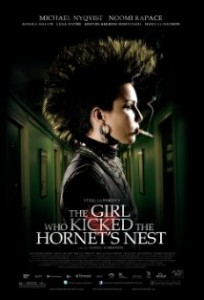

Most peopl e who see this film are probably already well familiar with the story surrounding Lisbeth Salander, the unlikely “heroine” of the trilogy by Swedish author Stieg Larsson. Director Daniel Alfredson, who also directed The Girl Who Played with Fire, apparently also assumes this, as he spends little time giving background, instead showing quick cuts of a few scenes from the two earlier films and allowing Lisbeth’s background to unfurl through her trial for murder. Beginning the film at about the halfway point of the final novel, Alfredson also omits most of the danger represented by her father, Alexander Zalachenko, a Russian defector who is trying to kill her in the hospital where they are both patients recuperating from life-threatening injuries. Zalachenko (Georgi Staykov) has only a cameo role here.

e who see this film are probably already well familiar with the story surrounding Lisbeth Salander, the unlikely “heroine” of the trilogy by Swedish author Stieg Larsson. Director Daniel Alfredson, who also directed The Girl Who Played with Fire, apparently also assumes this, as he spends little time giving background, instead showing quick cuts of a few scenes from the two earlier films and allowing Lisbeth’s background to unfurl through her trial for murder. Beginning the film at about the halfway point of the final novel, Alfredson also omits most of the danger represented by her father, Alexander Zalachenko, a Russian defector who is trying to kill her in the hospital where they are both patients recuperating from life-threatening injuries. Zalachenko (Georgi Staykov) has only a cameo role here.

For much of this film, actress Noomi Rapace, as Lisbeth, does not speak, instead conveying information through her facial expressions, allowing the viewer to see up close just how good an actress she is and how much she can convey with the blink (or lack of a blink) of an eye. Lisbeth is certainly a disturbed individual–angry, unable to trust anyone, reclusive, and no stranger to using violence to solve her problems–but much of this behavior is a result of her institutionalization and the physical and sexual abuse by virtually all the men which whom she came in contact as a child, including the care-givers assigned to her by the state.

When Lisbeth is finally released from the hospital for trial, Rapace plays the role to the hilt, and her close-ups in the courtroom are stunning–her eyes going dead, her slight grimaces, her blank expressions, her palpable vulnerability. Represented in court by Mikael Blomqvist’s sister Annika Giannini (played with wonderful subtlety by Annika Hallin), she appears to be everything that the uncompromising legal system abhors, and she does nothing to help herself. As in the past, Michael Nyqvist plays the role of Mikael Blomqvist, the caring writer/publisher of Millenium Magazine who wants to help her. As he and the staff of Millenium investigate the circumstances surrounding Lisbeth’s assignment to a mental institution at the age of twelve, and the accusations of abuse which she has made, the contrast between their commitment and active involvement in her future and the lack of affect that she shows toward her own future is dramatic and moving.

When Lisbeth is finally released from the hospital for trial, Rapace plays the role to the hilt, and her close-ups in the courtroom are stunning–her eyes going dead, her slight grimaces, her blank expressions, her palpable vulnerability. Represented in court by Mikael Blomqvist’s sister Annika Giannini (played with wonderful subtlety by Annika Hallin), she appears to be everything that the uncompromising legal system abhors, and she does nothing to help herself. As in the past, Michael Nyqvist plays the role of Mikael Blomqvist, the caring writer/publisher of Millenium Magazine who wants to help her. As he and the staff of Millenium investigate the circumstances surrounding Lisbeth’s assignment to a mental institution at the age of twelve, and the accusations of abuse which she has made, the contrast between their commitment and active involvement in her future and the lack of affect that she shows toward her own future is dramatic and moving.

Unlike the previous films, there is very little dramatic violence here, though Lisbeth’s confrontation with her giant brother Ronald Niedermann (Micke Spreitz), who is unable to feel pain, is one of the film’s high points. There are no graphic sex scenes, and the only sexual abuse is done off-camera. The Swedish setting–and the mood–are dark and cold, paralleling the life of Lisbeth Salander. The final scene, subtly different from the novel, consists of Lisbeth uttering one word–a word that had as much long-term dramatic effect for me as the word “Rosebud” does in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Ultimately, the viewer feels a kind of peace at the end of the film, a sensitive and satisfying conclusion to this trilogy.

Unlike the previous films, there is very little dramatic violence here, though Lisbeth’s confrontation with her giant brother Ronald Niedermann (Micke Spreitz), who is unable to feel pain, is one of the film’s high points. There are no graphic sex scenes, and the only sexual abuse is done off-camera. The Swedish setting–and the mood–are dark and cold, paralleling the life of Lisbeth Salander. The final scene, subtly different from the novel, consists of Lisbeth uttering one word–a word that had as much long-term dramatic effect for me as the word “Rosebud” does in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Ultimately, the viewer feels a kind of peace at the end of the film, a sensitive and satisfying conclusion to this trilogy.

The trailer for this film may be viewed here: