Note: Thomas Keneally was WINNER of the Booker Prize for Schindler’s List (Ark) in 1982. He is a two-time WINNER of Australia’s highest award, the Miles Franklin Award in 1967 and 1968, and has been WINNER of the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award in 2007.

“[Boney] turned to me, his eyes playful, and waved his finger in front of my face as if to get my attention, and reached forward and chose an ear that happened to have been pierced the day before. He knew it had been pierced, too… And now he squeezed it…inflicting pain as children do, and with the same fierce intent of children.” –Betsy Balcombe, age thirteen, during an encounter with Napoleon in his exile on St. Helena, 1815.

In 2012 Australian author Thomas Keneally’s prodigious imagination was captured by a special exhibition of “Napoleon’s garments, uniforms, furniture, china, paintings, snuffboxes, military decorations, and memorabilia” on display at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. There he also found two gorgeous women’s dresses, made in France and displayed there on mannequins, furniture commissioned by Jacob Frere “who might have come as close to Heaven in their creation as any furniture maker in history,” porcelain and plate, paintings by Jacques-Louis David, a swatch of Napoleon’s hair, and a death mask. With a smirk in his “voice,” Keneally comments that he was “bowled over” by what he saw, explaining that “we people of the globe’s southernmost regions are used to going to Europe on interminable, brain-numbing flights to gawp at such items, but to do it in Australia was a delight.”

In 2012 Australian author Thomas Keneally’s prodigious imagination was captured by a special exhibition of “Napoleon’s garments, uniforms, furniture, china, paintings, snuffboxes, military decorations, and memorabilia” on display at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. There he also found two gorgeous women’s dresses, made in France and displayed there on mannequins, furniture commissioned by Jacob Frere “who might have come as close to Heaven in their creation as any furniture maker in history,” porcelain and plate, paintings by Jacques-Louis David, a swatch of Napoleon’s hair, and a death mask. With a smirk in his “voice,” Keneally comments that he was “bowled over” by what he saw, explaining that “we people of the globe’s southernmost regions are used to going to Europe on interminable, brain-numbing flights to gawp at such items, but to do it in Australia was a delight.”

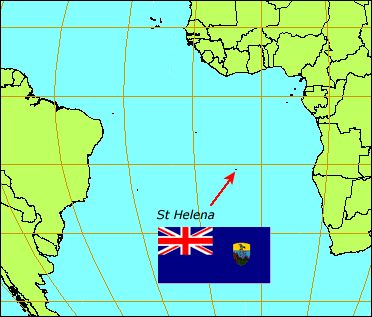

The exhibition catalogue featured the name of Betsy Balcombe and information about her and her family, people Napoleon knew during his exile on the tiny island of St. Helena, halfway between South America and Africa. Betsy was thirteen when Napoleon arrived there, and, author Keneally discovered, she and her family themselves were eventually exiled to Australia, bringing their mementoes of Napoleon with them. The exhibition, Betsy’s own journal, two volumes by Barry O’Meara (Napoleon’s physician on St. Helena), and journals by other friends of Napoleon on the island inspired Keneally to write this novel, which he describes as fiction “purporting to be a secret journal, the one hidden behind the real one” by Betsy Balcombe, published in 1844.

The exhibition catalogue featured the name of Betsy Balcombe and information about her and her family, people Napoleon knew during his exile on the tiny island of St. Helena, halfway between South America and Africa. Betsy was thirteen when Napoleon arrived there, and, author Keneally discovered, she and her family themselves were eventually exiled to Australia, bringing their mementoes of Napoleon with them. The exhibition, Betsy’s own journal, two volumes by Barry O’Meara (Napoleon’s physician on St. Helena), and journals by other friends of Napoleon on the island inspired Keneally to write this novel, which he describes as fiction “purporting to be a secret journal, the one hidden behind the real one” by Betsy Balcombe, published in 1844.

The novel’s beginning suggests Betsy’s own journal, being told in the first person by a young woman in England who has met her husband-to-be and who has just received word of Napoleon’s death, the details of which she and her parents learn from Barry O’Meara. Napoleon’s death in 1821, just six years after his arrival on the island, and only a few years after the Balcombes have been forced to leave the island for England, occur in the first twenty pages of the novel, which then flashes back. Part II, “Before OGF” (Our Good Friend) describes the Balcombes’ early lives on St. Helena, with intriguing descriptions of the island, the people there, their livelihoods, and their families. Betsy’s father William has become successful by maintaining a supply depot there for the East India Company. The arrival of Napoleon and his small entourage, and the lack of a ready place for him to stay, leads to his staying in the guest “pavilion” of the Briars, the home of the Balcombes, until his own house, Longwood, can be made ready.

The Pavilion at the Briars on St. Helena. Napoleon stayed here while construction was ongoing at Longwood, which would become his later home.

Thirteen-year-old Betsy, as she emerges in Keneally’s captivating novel, is a perfect foil for Napoleon Bonaparte, then in his mid-forties. Exiled to this remote island with no possibility of reprieve, he has brought with him all his war-time memories, a few furnishings, some assistants, two French ladies (the owners of the clothes on display in the Melbourne museum), and a strong need to adapt to a new life. A soldier from his late teens, he has had almost no childhood, and he is enchanted by the imaginative outdoor games played by Betsy and her friends, who help fill the emptiness left by the absence of his wife and son. When Betsy Balcombe gets pinched on the ear by Napoleon (in the opening quotation), she and other children have been playing after a day of studying and translating French into their native English. Betsy, energetic and uninhibited, has no awe of Napoleon, a characteristic which charms him – she talks back, argues with him, and acts without fear. The opening quotation takes place, in fact, after she has grabbed his sword and pretended to attack him, almost drawing blood.

Through all this lively description, Keneally keeps the spirit high, conveying more than physical appearances. When meeting Napoleon, Betsy’s little brothers “had had some solemnity threatened into them by our parents.” Napoleon, at dinner, quizzes them in French on country capitals, and asks Betsy who burned Moscow. As she tries to avoid accusing him of doing it, she finally responds, “What I’ve been told was that it was the Russians who burned it down to get rid of you, sir.” Napoleon’s delight in her answer sets the tone for the rest of their relationship: “I resolved,” Betsy later declares, “not to be treated with the kind of sport he clearly saw me as good for.” She later convinces her little brother to put a nasty substitute into a box of bonbons for Napoleon.

This tiny dot is St. Helena, between Africa and South America – and a very long way from Europe. Click to enlarge.

In later sections, Keneally uses the passage of time to develop new relationships and complications. The English governors of the island change, and with the arrival of Sir Hudson Lowe, an uncompromising man more anxious to mete out punishment than maintain peace, the Balcombe family is drawn into trying to help Napoleon in the “competition between the imperial bee [of Napoleon] and the Crown of Great Britain.” Budgets are cut back, food is more limited, and tensions rise on the island, both among the adults and among Betsy, her sister Jane, and some of the young men who may be courting them. One man is described by Betsy as “a vileness unsullied by mania and thus to be deplored.” Another is a “pink-eyed mouse.” The intense and surprising conclusion occurs after Betsy creates a social disaster which permanently affects the lives of everyone she knows. “Dry lids were my religion and indeed I would not cry now,” she declares. The island serves as a microcosm of the world in which themes of alienation and exile inform the lives of families and friends, in which life is often short and not always sweet, and in which revenge can be a potent weapon.

In an afterword, Keneally moves the Balcombes’ lives forward several generations to the time of the exhibition at the museum in Melbourne and the Balcombes’ eventual history there. He never says whether the dramas of the conclusion are real or fiction, but by the time the novel ends, the reader may be so charmed that he does not have to. Elegantly written in nineteenth century style, and old-fashioned in the best possible ways, this novel completely captivated me.

ALSO by Thomas Keneally: CONFEDERATES, DAUGHTERS OF MARS, SCHINDLER’S LIST, THE TYRANT’S NOVEL, VICTIM OF THE AURORA

Photos, in order: The author photo appears on https://www.theguardian.com/books Photo by International/REX Shutterstock

The photograph of Betsy Balcombe’s portrait appears on http://www.mrodenberg.com/ Ms. Rodenberg says of this portrait on her website: “Although the Balcombes’ main house at the Briars was destroyed long ago, Napoleon’s summer pavilion has survived, with additions built on over the years. The center room where Napoleon stayed is open to the public and contains memorabilia from his time there, including this oil painting of Betsy.”

The Pavilion, a guest house at The Briars, where the Balcombes lived, is shown on https://whatthesaintsdidnext.com/

Longwood House, which became Napoleon’s home on St. Helena is appears on https://commons.wikimedia.org Photo by Michel Dancoisne-Martin

The map of St. Helena is from https://www.pinterest.com/

The painting of “Napoléon à Sainte-Hélène” by Francois-Joseph Sandmann is from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Helena#/media/File:Napoleon_sainthelene.jpg

ARC: Atria Books