Note: This novel was WINNER of the National Book Award in 1975.

“[Author Aaron Benham] has always thought of a novel, before it has taken on its first, tentative structure, as a scene on a dark plain, the characters standing around a small fire which warmly etches the edges of their faces…It is that small fire he must constantly re-create or these last warm lives will cease to live, will never have lived even to fear the immensities…around them.”

In this supremely literary and exciting prize-winner from 1975, newly reprinted by Bloomsbury, Thomas Williams, an almost forgotten author, creates a novel about fiction writing and its relationship to the “immensities” with which every human being must contend, for better or worse, during his lifetime. Telling the story of a novelist who is writing a novel in which a character is also writing a novel, Williams creates, first, Aaron Benham, a professor at a small New England college in the 1970s. Benham is writing a novel entitled The Hair of Harold Roux, in which the “thinly disguised” hero is twenty-one year-old Allard Benson, who is a college student on the G. I. Bill just after the close of World War II. Allard Benson does not believe in violence, but he would “kill the world for girls like Mary Tolliver,” an especially innocent, eighteen-year-old freshman who has had a very protected and very Catholic upbringing, and whom he is trying to seduce.

In this supremely literary and exciting prize-winner from 1975, newly reprinted by Bloomsbury, Thomas Williams, an almost forgotten author, creates a novel about fiction writing and its relationship to the “immensities” with which every human being must contend, for better or worse, during his lifetime. Telling the story of a novelist who is writing a novel in which a character is also writing a novel, Williams creates, first, Aaron Benham, a professor at a small New England college in the 1970s. Benham is writing a novel entitled The Hair of Harold Roux, in which the “thinly disguised” hero is twenty-one year-old Allard Benson, who is a college student on the G. I. Bill just after the close of World War II. Allard Benson does not believe in violence, but he would “kill the world for girls like Mary Tolliver,” an especially innocent, eighteen-year-old freshman who has had a very protected and very Catholic upbringing, and whom he is trying to seduce.

Harold Roux, also a veteran studying on the G. I. Bill, is, like Mary, an extremely sensitive and devout Catholic, a young man who is happy that he will no longer have to experience “the crudity, the vulgarity, and sheer horror of barracks life.” Harold, who lost his hair during the war, made a “Midas choice” the day after his discharge, purchasing a terrible toupee which he believes makes him more attractive to women. A true romantic despite the mockery and bullying he faces from the cruder, crueler students, Harold is writing a love story called Glitter and Gold, for which he and Mary are the models for Francis Ravendon and Allyson Turnbridge. Within this story Francis has also written a novel which Allyson has read, adding yet another level of fiction here, with Harold Roux, the “real” author of this story within the story within the story, justifying the novel’s romanticism by asking “Isn’t it the truth if you believe it? Fiction is the truth, isn’t it?”–a question which gets at the heart of writing and its purpose.

Williams tells the reader at the outset that the story Aaron Benham is creating is “a simple story of seduction, rape, madness and murder—the usual human preoccupations,” but that is a misleading summary. Aaron’s novel, set in the 1940s, is actually a well drawn character study of people dealing with their lives, their expectations, and the world as they see it within the microcosm of a small college. Here bullies collect weaker supporters around them, “nice” people are sometimes victimized, and the issues of sex are complicated by the new social milieu of the post-war campus. Soldiers returning from overseas have seen the worst life has to offer in warfare, while the co-eds have often been brought up in virtual seclusion, with most of the boys their own age off fighting. New political ideas celebrated by the more intellectually adventurous women have also helped promote greater sexual liberation among some women. Life on campus is a churning milieu in which many unprepared people are trying to cope with change.

While writing this novel set in the 1940s, Prof. Aaron Benson is also living his own life in the 1970s, five years before the end of the Vietnam War. Many of his students are active in the culture of “turn on, tune in, drop out” and in radical politics. The competitive, internecine maneuvering within college departments dealing with tenure and the “publish or perish” requirement have made the life of at least one of Aaron’s friends a misery, while exerting pressure on Aaron himself. His need to write his novel has created some problems in his marriage, and he is feeling “itchy,” often inventing fantasies about what he has missed with regard to other women. When he goes deep sea fishing with a group of drunks one weekend, he discovers life at one of its lowest levels, “poor, deformed organisms” whose casual cruelty reveals Aaron’s own “fascination with the abomination.” But it is the sometimes frightening stories he creates for his children, ages six and eight, that reveal his preoccupation with the dramatic effects of fiction. Cuddling with them on the couch as he spins his stories, he literally “feels the story with their reality,” an event so full of emotion that “he loses his voice.”

While writing this novel set in the 1940s, Prof. Aaron Benson is also living his own life in the 1970s, five years before the end of the Vietnam War. Many of his students are active in the culture of “turn on, tune in, drop out” and in radical politics. The competitive, internecine maneuvering within college departments dealing with tenure and the “publish or perish” requirement have made the life of at least one of Aaron’s friends a misery, while exerting pressure on Aaron himself. His need to write his novel has created some problems in his marriage, and he is feeling “itchy,” often inventing fantasies about what he has missed with regard to other women. When he goes deep sea fishing with a group of drunks one weekend, he discovers life at one of its lowest levels, “poor, deformed organisms” whose casual cruelty reveals Aaron’s own “fascination with the abomination.” But it is the sometimes frightening stories he creates for his children, ages six and eight, that reveal his preoccupation with the dramatic effects of fiction. Cuddling with them on the couch as he spins his stories, he literally “feels the story with their reality,” an event so full of emotion that “he loses his voice.”

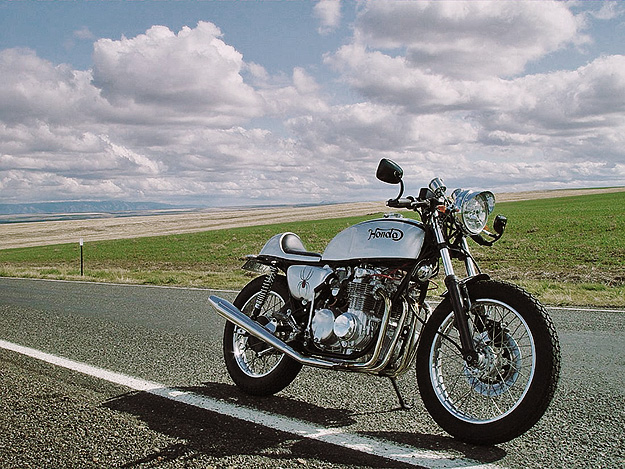

Within this rough outline of the novel, Williams writes some of the best and most excitingly sensuous descriptions ever. Both Aaron Benham and his creation, Allard Benson, love motorcycles, and both have scenes here in which they express the feeling of freedom they achieve as they fly down the road, Aaron indicating that he “feels the symmetry of having made something out of chaos” simply by arriving home safely. When Allard meets Mary Tolliver’s father, he notes that “Mr. Tolliver’s skin was yellow-brown, his glasses tinted sepia like an old rotogravure. The skin of his face and neck hung as though draped over his head and tacked here and there, at the corners of his eyes and where his ears were attached to his head.” When Allard visits the home of Col. Immingham, inside a miniature village which the Colonel has made to honor his wife, he rides on a hand-crafted railway with a 1/6 scale locomotive from the Prussian State Railways of 1880. Sporting “three brass lanterns on its front end…the engine seemed to peer straight ahead with the powerful

Within this rough outline of the novel, Williams writes some of the best and most excitingly sensuous descriptions ever. Both Aaron Benham and his creation, Allard Benson, love motorcycles, and both have scenes here in which they express the feeling of freedom they achieve as they fly down the road, Aaron indicating that he “feels the symmetry of having made something out of chaos” simply by arriving home safely. When Allard meets Mary Tolliver’s father, he notes that “Mr. Tolliver’s skin was yellow-brown, his glasses tinted sepia like an old rotogravure. The skin of his face and neck hung as though draped over his head and tacked here and there, at the corners of his eyes and where his ears were attached to his head.” When Allard visits the home of Col. Immingham, inside a miniature village which the Colonel has made to honor his wife, he rides on a hand-crafted railway with a 1/6 scale locomotive from the Prussian State Railways of 1880. Sporting “three brass lanterns on its front end…the engine seemed to peer straight ahead with the powerful  yet slightly moronic, clownish intensity of a cyclops.” He believes that the little village is obviously “someone’s ideal place, [and] that a segment of another world had been created here,” a fiction made from wood and metal rather than words.

yet slightly moronic, clownish intensity of a cyclops.” He believes that the little village is obviously “someone’s ideal place, [and] that a segment of another world had been created here,” a fiction made from wood and metal rather than words.

Constantly playing with fiction vs. reality, fiction as part of reality, fiction as an alternative to reality, and the special fictions one creates for love, the author writes a powerful and dramatic novel, filled with events which keep the reader constantly involved with his characters, even when they are behaving badly. It is only when sordid reality destroys all the fictions someone has created in order to cope with everyday life, that one recognizes just how important it is to keep going by creating newer but more realistic fictions. (This novel is at the top of my Favorites List for the year right now.)

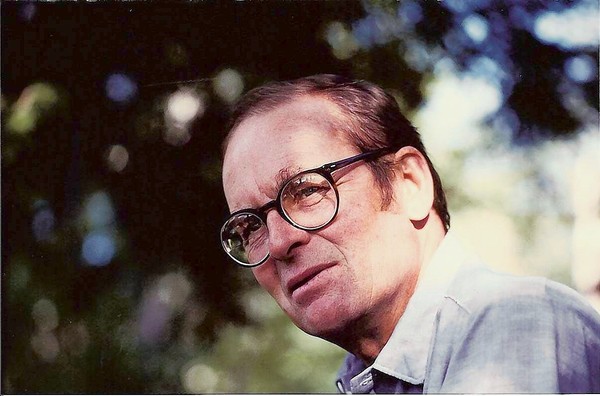

Photos related to the action, in order: The author’s photo, by Peter Williams/Bloomsbury, is from http://articles.latimes.com

The Honda CB550, from 1975, ridden regularly by Aaron Benham is from http://www.bikeexif.com

Allard Benson’s Indian Pony motorcycle, from the late 1930s, appears on http://motorbike-search-engine.co.uk

The child at a miniature village, and the photo of the train at the same village are http://www.bekonscot.co.uk. Colonel Immerson built a similar village for his wife, Morgana, and it features in several important scenes in this novel. His locomotive was a model based on the Prussian Railway locomotive from the 1880s.