“Despite everything, I want to live! And that requires all the wits I have, but they aren’t enough, because the same reasoning is pitting me against myself. It negates my existence. So where does that leave me? It’s because I understand…that I despair. If only I could misunderstand. But that’s something I’m no longer able to do. [All] I have left in life is the list of all my losses.”

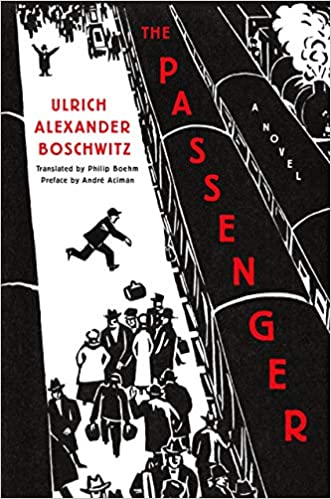

Like The Diary of Ann Frank, Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s The Passenger is also written by someone who began to write about the horrors of the Holocaust while they were actually happening, and while the author was living through its personal tragedies. Boschwitz’s novel, however, offers a significantly different focus from Anne Frank’s diary, providing additional dimensions of reality while sacrificing some of its intimacy. Whereas Anne Frank is a young girl living in hiding with her family in Amsterdam and telling their story, Boschwitz, author of The Passenger, is twenty-three, a recent college graduate who wrote this book as fiction over the course of one frantic month in Berlin in the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht. Creating the fictional story of Otto Silbermann, a married businessman/owner of a successful scrap and salvage company in Berlin, Boschwitz gives realistic details about life in the city, describing a man who has always been dedicated to his business and fair to his employees, who loves his family, and who has a long history of hard work, even serving in the German military during World War I. After Kristallnacht, however, as life for Jews throughout Germany becomes ever more difficult, Silbermann finds all escapes from Nazi control closed, and takes what he regards as the only way out. He becomes a “passenger,” a man who travels from city to city by train almost non-stop, sometimes not getting out when he arrives at his “destination” in order to avoid being being identified and possibly arrested for being a Jew. It is a hopeless existence.

Early in the novel, after Silbermann negotiates the sale of his business and his apartment house to an Aryan who had worked for him and who now exploits his sad reality, Silbermann is anxious to escape the city. Having sold for cash, however, he now must carry the entire sale proceeds packed into a briefcase as he travels through Germany. Unable to reconnect with his wife, and with the security forces actively looking for him, he decides to take the train from Berlin to Aachen, a city at the junction of Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The attitudes of those on the train, mostly in agreement with the government, make the trip more difficult, and one man in his compartment, a Jew, is trying to figure out how to bribe an official at the border so he can escape into Belgium or the Netherlands.

Eventually he is able to hire a driver to take him to the border of Belgium, from which he plans to walk to safety, but he has no luck with that plan and must return to Aachen, and, later, head back to Berlin. Ursula Angelhof, an attractive woman from the train whom he regards as a possible helper – and not incidentally, someone who can help make him feel less lonely – is also going to Berlin, and she agrees to meet him at the Gedachtniskirche, the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, later that day. He is happily married, but he feels he needs someone to share what he has been going through, and his wife is with her Aryan family, which is not anxious to see him at this point. Circumstances intervene, and he is left with the advice of Ursula, his friend, to “start living as though each day were [his] last.” He believes that if he can do this, and get to know the places he visits, at least a little bit, that his constant movement might seem “a little less grindingly senseless.” He continues his train travel.

The funicular in Dresden which goes up the mountain to a spectacular view.

Ultimately, Silbermann travels to Dresden, trying to decide whether to return eventually to Berlin. His panic is driving him to make irrational decisions, and even leads to a brief medical intervention, but at last he decides to take the funicular from Dresden up to the Weisser Hirsch to see the spectacular view, which he hopes will affect his will and his confidence. On finally deciding to return to Berlin, he falls asleep, exhausted, on the train. When he awakens, he realizes that his briefcase, carrying every cent he has left in the world, has been stolen. The constable on the train cannot help him. As the train starts up again, Silbermann reveals the depth of his depression and loss of motivation.

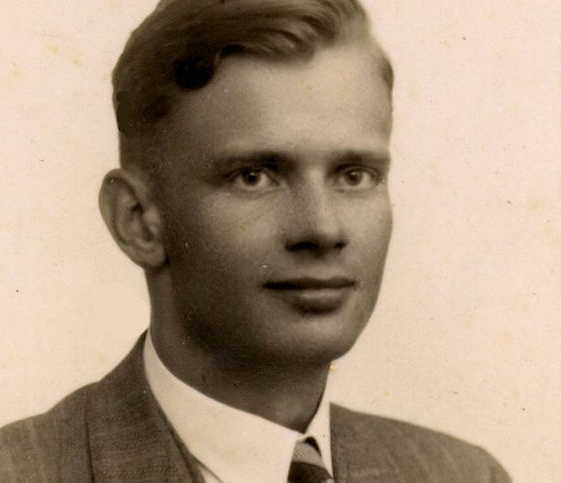

Hiding within this “fictional” story are aspects similar to what author Boschwitz himself experienced during this same period. In the Afterword by Peter Graf, the real life of Boschwitz himself is shown to resemble that of the fictional Silbermann in some key aspects. Eventually, the author was able to escape Germany and become a young exile in England, where he became part of the internment system, which declared him an “enemy alien.” Isolated, alone, and unwanted, he was out of Germany, but not free in England. The Afterword provides additional details of Boschwitz’s real, post-Kristallnacht life, made even more affecting to the reader because s/he has already shared the life and thoughts of his main character Silberman whose experiences were similar and equally grim.

Author Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, who wrote The Passenger when he was in his early twenties. Photo courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

Reading and responding to a book like this, which was written by a very young author trying to cope with the very real horrors of Nazi rule requires some special considerations, I believe. It is possible to criticize the wandering nature of Silvermann, his unplanned train trips, and the lack of coherence in the novel as he tells his seemingly unplanned story. On the other hand, that very lack of coherence and the frantic movement of the story itself is certainly characteristic of the main character acting out his panic attacks and fears of the future. Author Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz has something to say, and real life and its emergencies are not necessarily as “neat” and carefully ordered as literary fiction. This book rings true. It is powerful and intense as a vision of life, and I cannot imagine any reader who will not be strongly affected by this “novel” of life in Berlin as the Nazis get ready for their world war.

Translation: Philip Boehm. Preface: Andre Aciman. Afterword: Peter Graf.

Photos. The photo of the border of Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands appears on https://www.tripadvisor.com

The Gedachtniskirche, the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, where Silbermann had hoped to meet Ursula, was destroyed during World War II. https://en.wikipedia.org

Silbermann takes the funicular in Dresden to Weisser Hirsch, a beautiful ride, hoping to lift his depression a bit. https://en.wikipedia.org Photo by Chris J Wood

Silbermann keeps all of the money he has in a briefcase, perhaps similar to this one from World War II. https://www.antiquesnavigator.com

The author photo may be found on https://insidestory.org.au/hell-or-high-waters Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York