“There has been lots of talk about women driving cars. It is well-known that this will lead to immoral and licentious acts, of which those who call for it are not unaware, among them the possibility of a woman going out on her own, which is forbidden by the Faith. Such situations lead to the public display of women’s faces, and mixing with men without restriction or limitation, and the committing of unlawful acts, for which reason these matters are haram.”

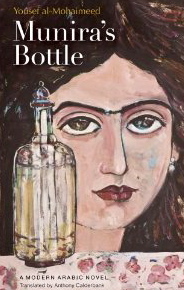

Saudi a uthor Yousef al-Mohaimeed, whose book, according to Scott Wilson of the Washington Post, sold five hundred copies in just three days at one bookshop in Riyadh, is certain to gain western readers with his intense and often moving story of a love gone wrong. Munira al-Sahi, a beautiful thirty-year-old woman, has been studying for her graduate degree and working at a counseling center for abused girls and women in Riyadh. She also writes a once-a-week column for a local newspaper. Though she has heard all manner of terrible life stories from the women she counsels, she never suspects she herself will become another sad statistic: the man who has been courting her is an impostor, someone who is using her to gain revenge on one of her brothers by ruining her life and making her his legal and emotional prisoner forever.

uthor Yousef al-Mohaimeed, whose book, according to Scott Wilson of the Washington Post, sold five hundred copies in just three days at one bookshop in Riyadh, is certain to gain western readers with his intense and often moving story of a love gone wrong. Munira al-Sahi, a beautiful thirty-year-old woman, has been studying for her graduate degree and working at a counseling center for abused girls and women in Riyadh. She also writes a once-a-week column for a local newspaper. Though she has heard all manner of terrible life stories from the women she counsels, she never suspects she herself will become another sad statistic: the man who has been courting her is an impostor, someone who is using her to gain revenge on one of her brothers by ruining her life and making her his legal and emotional prisoner forever.

Through his focus on Munira, Yousef al-Mohaimeed reveals a much larger purpose than just a sad love story. Here he recreates the lives of many seemingly typical Saudi women in 1990, a time in which American Patriot missiles and Russian Scuds are streaking through the sky in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. The country is also beginning to feel the first effects of the growing jihadist movement even as some women have been pushing fo r more freedom. Though Munira has been attending graduate school and has many women friends who are much more rebellious than she is, she remains true to the cultural traditions of her family and religion, rejecting the plea that she join thirteen women who plan to demonstrate by driving cars in Riyadh. She describes her life this way: “I am a female. Just a female with clipped wings. That’s how people see me in this country. A female with no power and no strength. My sole purpose is to receive, like the earth receives the rain and the sunlight and the plough.”

r more freedom. Though Munira has been attending graduate school and has many women friends who are much more rebellious than she is, she remains true to the cultural traditions of her family and religion, rejecting the plea that she join thirteen women who plan to demonstrate by driving cars in Riyadh. She describes her life this way: “I am a female. Just a female with clipped wings. That’s how people see me in this country. A female with no power and no strength. My sole purpose is to receive, like the earth receives the rain and the sunlight and the plough.”

Evocative descriptions of the natural world create moods, atmosphere, and the kind of detail which will be new and perhaps spell-binding to most western readers. (A vibrant picture of a quiet afternoon in this “desert city,” and the description of an abaya-clad seller at the souk finding a way to accept the phone number of an interested man, surreptitiously, are particularly memorable scenes.) Moving back and forth chronologically, al-Mohaimeed tells stories within stories, enlivening the jottings about life  which Munira pens and places in a painted bottle given to her by her grandmother. Through changing points of view, the reader is taken on a journey through the lives of Saudi women of all classes, even as Munira’s own disastrous engagement to Ali al-Dahhal is rocketing back and forth between the catastrophe at the end of the relationship and the passionate lead-up to it. These personal stories assume additional power through the author’s creation of parallels to aspects of the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein and Kuwait. Though Munira has adhered to religious and cultural strictures regarding her virginity, she feels, understandably, that she has been assaulted, her hopes and anticipation of marriage sabotaged. Honor and the perception of honor are everything in her world.

which Munira pens and places in a painted bottle given to her by her grandmother. Through changing points of view, the reader is taken on a journey through the lives of Saudi women of all classes, even as Munira’s own disastrous engagement to Ali al-Dahhal is rocketing back and forth between the catastrophe at the end of the relationship and the passionate lead-up to it. These personal stories assume additional power through the author’s creation of parallels to aspects of the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein and Kuwait. Though Munira has adhered to religious and cultural strictures regarding her virginity, she feels, understandably, that she has been assaulted, her hopes and anticipation of marriage sabotaged. Honor and the perception of honor are everything in her world.

Munira’s world becomes infinitely more complex and more restricted when one of her brothers, who also lives at home, returns from helping the Afghans fight the Russians and commits himself to a fundamentalist view of Islam and the establishment of an Islamic state. His reading aloud of fatwas by the mufti reveal just how much more restricted the lives of women will become if the strictest interpretations of the Koran become law. And when Munira goes to court to resolve her difficulties with Ali al-Dahhal, her true position in society, relative to that of Ali, will stun western readers. With a strong story involving Munira and her duplicitous suitor and revelations galore regarding issues that western women take for granted, this novel excites even as it teaches. Readers interested in other cultures will find this book one of the most specific and least sugar-coated novels about the Middle East they have read, and if even a few book clubs discover it, their discussions should lead to big word-of-mouth sales.

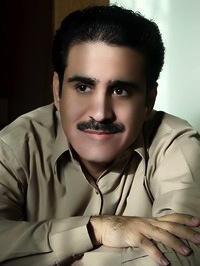

Notes: The author’s photo by Huda Saleh appears on his website: www.al-mohaimeed.net

Also on that site, is Scott Wilson’s Washington Post story which reveals that after selling five hundred copies in three days in Riyadh in 2005, a group of religious and political conservatives invaded the bookstore and removed all the remaining copies of the book. See www.al-mohaimeed.net

The photo of Riyadh is from www.toursaudiarabia.com. The subsequent photo of the camels in the truck on a main highway (by David Malloch) shows the contrasts one will find in this lively city. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/951330/Big-Picture-shortlist-round-four.html?image=3