“If the revolution is over, and in a sense it is, it’s because the dead of Africa, their mouths full of earth, cannot protest…and we, the survivors, are still so doubtful of our own existence that, given our inability to move, we fear that our gestures lack flesh and our words sound, that we are as dead as they are.”

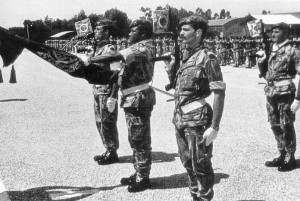

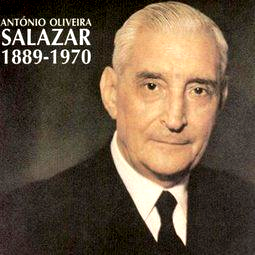

In this high-tempe rature fever dream of a novel, written originally in 1979 and newly translated, the images often seize and explode with powerful emotion. Author Antonio Lobo Antunes describes the life of a newly graduated Lisbon physician who has been sent to Angola from 1971 – 1973, during Portugal’s war to preserve its colonies, along with its traumatic aftermath. As the novel begins, six years have passed since the speaker has returned to Lisbon from Angola, but the young physician still cannot come to grips with all he saw and felt there. Furious by the betrayal of the Portuguese government, consisting of the ultra-right wing Estado Novo led for many years by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (or “the Castrato, as the speaker calls him), the speaker accuses that government of responsibility for all the Angolan and Portuguese dead and for the living, but lost, souls who had to fight a war which they, as soldiers on the ground, could see made no sense at all. At one point he explodes in rage: “Standing at the door of the operating room, with the barracks dogs sniffing at my clothes, greedy for the blood of my wounded comrades,” he cries, “I hated the people who were lying to us and oppressing us and humiliating and killing us in Angola, [those] serious, dignified gentlemen in Lisbon stabbing those of us in Angola in the back, the politicians, magistrates, policemen, informers, and bishops…”

rature fever dream of a novel, written originally in 1979 and newly translated, the images often seize and explode with powerful emotion. Author Antonio Lobo Antunes describes the life of a newly graduated Lisbon physician who has been sent to Angola from 1971 – 1973, during Portugal’s war to preserve its colonies, along with its traumatic aftermath. As the novel begins, six years have passed since the speaker has returned to Lisbon from Angola, but the young physician still cannot come to grips with all he saw and felt there. Furious by the betrayal of the Portuguese government, consisting of the ultra-right wing Estado Novo led for many years by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (or “the Castrato, as the speaker calls him), the speaker accuses that government of responsibility for all the Angolan and Portuguese dead and for the living, but lost, souls who had to fight a war which they, as soldiers on the ground, could see made no sense at all. At one point he explodes in rage: “Standing at the door of the operating room, with the barracks dogs sniffing at my clothes, greedy for the blood of my wounded comrades,” he cries, “I hated the people who were lying to us and oppressing us and humiliating and killing us in Angola, [those] serious, dignified gentlemen in Lisbon stabbing those of us in Angola in the back, the politicians, magistrates, policemen, informers, and bishops…”

After bedding a woman he has just met, he is suddenly impelled to tell her about his experiences in Angola, and, once started, he cannot stop. “I am a tender soul,” he says, “very tender, even before I’ve had my sixth neat Jim Beam or my eighth Drambuie.” As his life in Angola unfolds in this long monologue, he is constantly aware of how much he has changed and how much he has lost. “Perhaps,” he says, “the war has helped to make me the person I am today whom I deep down reject: a melancholic bachelor whom no one phones and from whom no one expects a call, who coughs occasionally just to feel as if he has company.”

After bedding a woman he has just met, he is suddenly impelled to tell her about his experiences in Angola, and, once started, he cannot stop. “I am a tender soul,” he says, “very tender, even before I’ve had my sixth neat Jim Beam or my eighth Drambuie.” As his life in Angola unfolds in this long monologue, he is constantly aware of how much he has changed and how much he has lost. “Perhaps,” he says, “the war has helped to make me the person I am today whom I deep down reject: a melancholic bachelor whom no one phones and from whom no one expects a call, who coughs occasionally just to feel as if he has company.”

The intensity of the feelings and images throughout this book belie the usual objectivity of a novelist. Like his speaker, the author, too, was a young physician when he was sent to perform military service in Angola from 1971 – 1973, and though this is considered a novel, it is obviously extremely autobiographical. At one point the speaker even calls the lover to whom he is telling his story, six years later, “Maria Jose,” the name of the author’s former wife, by whom he had two daughters.

The rich , thick descriptions of the countryside and its activity are so life-like that the reader sometimes feels like squinting—images almost too intense to process. In one fairly typical paragraph, in which he describes his arrival in Luanda, the speaker notes that “the water resembled murky sun lotion smeared onto old, grubby skin veined with rotting cables.” Thick with vegetation and insects, the harbor also features “whores, worn out by heartless men from Lisbon…like dying whales stranded on a final beach.” The paragraph continues: Black men sitting along the pier are “watching with timeless absorption, simultaneously acute and blind, [as] you see in photographs showing the closed, inward-turned eyes of John Coltrane as he played his bittersweet, drunken-angel music on the saxophone.” And, he concludes, “I’ve always been in favor of erecting in some suitable square in Portugal a monument to spit, a spitting bust, a spitting marshal…a spitting equestrian statue…something that would provide, in the future, a perfect definition of the perfect Portuguese male; someone who spits and boasts about his sexual prowess.”

, thick descriptions of the countryside and its activity are so life-like that the reader sometimes feels like squinting—images almost too intense to process. In one fairly typical paragraph, in which he describes his arrival in Luanda, the speaker notes that “the water resembled murky sun lotion smeared onto old, grubby skin veined with rotting cables.” Thick with vegetation and insects, the harbor also features “whores, worn out by heartless men from Lisbon…like dying whales stranded on a final beach.” The paragraph continues: Black men sitting along the pier are “watching with timeless absorption, simultaneously acute and blind, [as] you see in photographs showing the closed, inward-turned eyes of John Coltrane as he played his bittersweet, drunken-angel music on the saxophone.” And, he concludes, “I’ve always been in favor of erecting in some suitable square in Portugal a monument to spit, a spitting bust, a spitting marshal…a spitting equestrian statue…something that would provide, in the future, a perfect definition of the perfect Portuguese male; someone who spits and boasts about his sexual prowess.”

The speaker’s personal, emotional reactions are even more vivid. Receiving the news that his wife has given birth to a daughter, he cynically imagines that back in Lisbon, “the patriots of the National Union Party are thinking of us as they buy black, see-through underwear for their secretaries …businessmen are thinking of us as they manufacture modestly priced armaments, the Government is thinking of us as it awards miserable little pensions to the widows of soldiers, and we, wretched ingrates, the target of so much love, either leave our barbed-wire compounds to be killed, out of sheer perversity, by a mine or in an ambush or we negligently leave behind us fatherless children who will be taught to point at our photo next to the television, in family rooms we have never known…”

Then, in an anguished cry, he asks, “What have they done to my people, what have they done to us, sitting here waiting in this landlocked place, imprisoned by three rows of barbed wire in a land that doesn’t belong to us, dying of malaria and bullets…fighting an invisible enemy, fighting the endless days that never pass..fighting the dark nights as thick and opaque as a mourning veil that I draw over my head in order to sleep, just as when I was a child, I used the edge of my sheet to protect myself from the phosphorous blue eyes of my ghosts.”

Then, in an anguished cry, he asks, “What have they done to my people, what have they done to us, sitting here waiting in this landlocked place, imprisoned by three rows of barbed wire in a land that doesn’t belong to us, dying of malaria and bullets…fighting an invisible enemy, fighting the endless days that never pass..fighting the dark nights as thick and opaque as a mourning veil that I draw over my head in order to sleep, just as when I was a child, I used the edge of my sheet to protect myself from the phosphorous blue eyes of my ghosts.”

The novel contains remarkably little battle action, stressing instead the effects of war and setting on one sensitive young physician who is still traumatized six years after he has returned home. The density of these descriptions becomes so overwhelming, at times, that the reader becomes almost immune to them—and that is the supremely ironic parallel to the speaker’s discoveries on his return. The reader becomes the equivalent of the speaker’s friends, family, and countrymen who simply cannot process all that the speaker has to say or the misery that so affects his life. A mere six years after his return, he sees that for everyone around him, “Everything is real apart from the war, which never existed: there were never any colonies, no Fascism, no Salazar, no Tarrafal prison camp…the calendars of this country stopped moving so long ago that we’ve forgotten all about them…”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.tintafresca.net

The map of Angola is from http://www.swimmikeswim.com

The army uniform of Portugal during the war in Angola is seen on http://www.scribd.com

The photo of Antonio Oliveira Salazar, who founded and led Estado Novo for many years, is found here: http://guinevereuniversidade.blogspot.com