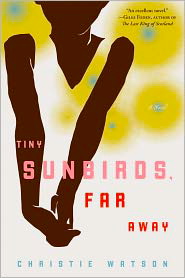

Note: This novel is WINNER of the Costa Award for First Novel for 2011.

“We are sick of the failed promises. Sick of sickness. Sick of our environment filled with pollution and our rivers filled with oil spills. Sick of guns. Sick of no electricity. Sick of our government putting billions of pounds in their own pockets. We are sick of the oil companies giving these men money, knowing it will not go to the people.”

Twelve-year-old Blessing and her fourteen-year-old brother Ezekiel find their comfortable lives in suburban Lagos dramatically changed when their parents suddenly separate and they must follow their mother to her native village, a tiny community near Warri in the Niger Delta. There they find life completely different—no electricity, no generator, no air conditioning, no refrigerator, no running water or flush toilets, no separate bedrooms, and a school system that uses harsh corporal punishment for the most minor of infractions. Living in a small house with their grandparents, while their mother takes the only job she can get at a bar at the nearby oil company compound, Blessing and Ezekiel quickly learn what it is like having almost no money while living in an area with some of the richest oil deposits in the world. The profits from this incredible resource are unavailable to ordinary Nigerians who live on top of these deposits, yet it is these local residents who must cope with the fatal pollution of the Niger Delta–the largest wetland area in the world.

Twelve-year-old Blessing and her fourteen-year-old brother Ezekiel find their comfortable lives in suburban Lagos dramatically changed when their parents suddenly separate and they must follow their mother to her native village, a tiny community near Warri in the Niger Delta. There they find life completely different—no electricity, no generator, no air conditioning, no refrigerator, no running water or flush toilets, no separate bedrooms, and a school system that uses harsh corporal punishment for the most minor of infractions. Living in a small house with their grandparents, while their mother takes the only job she can get at a bar at the nearby oil company compound, Blessing and Ezekiel quickly learn what it is like having almost no money while living in an area with some of the richest oil deposits in the world. The profits from this incredible resource are unavailable to ordinary Nigerians who live on top of these deposits, yet it is these local residents who must cope with the fatal pollution of the Niger Delta–the largest wetland area in the world.

A close-up view of the lives of an Ijaw family in a small village, which peacefully supports both Christian and Muslim religions, the novel is more personal and descriptive than it is plot-based. Very little actually “happens” during the first hundred pages, as author Christie Watson, who lived in Nigeria for several years, creates a family which is remarkably real, living a life which rings true in the smallest of details. Ezekiel becomes very close to his grandfather, a Muslim preacher (newly converted from Christianity) who has created an outdoor mosque behind their house, and they are observant (except for Grandfather’s alcohol consumption). The children’s grandmother and mother both turn over their earnings to the grandfather, who is always on the verge of “getting a job as a petroleum engineer” at the oil company, though never succeeding, spending his time at The Executive Club instead, drinking brandy and talking about all his big plans. When they repeatedly run out of money for the barest necessities and Blessing and Ezekiel have to drop out of school, they wonder where the money comes from that grandfather Alhaji uses to buy brandy. The fact that all the women in the family have full-time jobs, none of them high-paying, while Alhaji apparently does not work at all, makes the issues that much more emotional. The women who are employed are already trying to support themselves and the family, plus a chauffeur, his four wives, and his seventeen children, all of whom live with them.

Blessing, who never is able to return to school after her initial experience there, becomes her grandmother’s assistant, delivering babies—and she and Grandmother, both together and separately, handle even the most complex obstetrical emergencies with confidence—and no anesthetics. This work allows the author to integrate an important subplot about the mutilation of young girls, often when they are infants, a problem which affects to up to eighty percent of the girls in very rural, very closed tribal communities. (The percentage in the larger, more open communities has been dropping steadily but is still an issue.) These young girls, who may be only thirteen or fourteen when they have their first babies, have a very high rate of complications as a result of their mutilations, with deaths to the mothers and babies not uncommon. Blessing is horrified by this discovery.

Blessing, who never is able to return to school after her initial experience there, becomes her grandmother’s assistant, delivering babies—and she and Grandmother, both together and separately, handle even the most complex obstetrical emergencies with confidence—and no anesthetics. This work allows the author to integrate an important subplot about the mutilation of young girls, often when they are infants, a problem which affects to up to eighty percent of the girls in very rural, very closed tribal communities. (The percentage in the larger, more open communities has been dropping steadily but is still an issue.) These young girls, who may be only thirteen or fourteen when they have their first babies, have a very high rate of complications as a result of their mutilations, with deaths to the mothers and babies not uncommon. Blessing is horrified by this discovery.

As Ezekiel, an asthmatic who also has peanut allergies, becomes thinner and thinner, unable to eat meat, which is always fried in peanut oil to counteract the spoilage due to lack of refrigeration, the characters in the family become more and more sympathetic. Olive oil or vegetable oil is extremely expensive, and their mother, on probation in her new job, has no way to “borrow” it from the bar. Blessing saves her vegetables for him so he won’t starve. The air pollution makes Ezekiel’s breathing problems even worse. These are exacerbated further by Alhaji who believes that Marmite is a cure-all, even when Ezekiel has run out of emergency injections for his allergic reactions and inhalers for his asthma. Timi, the mother, is helpless to change this.

As the lives of the Kentabe family unfold, the reader observes how they try to cope with rivers so polluted they cannot use the water, air that no one should have to breathe, trees and crops that will no longer grow in the soil, jobs that are given to foreigners and those with close ties to the government, poverty due to corruption of government officials, and the greed of the oil companies, most of them run by Americans. This pollution of the land, rivers, and air has continued unabated for over fifty years. As it continues to get worse, we see here, young Nigerians are organizing to seize “their heritage”–the oil under their land. Violence has become endemic. Blessing and Ezekiel are warned not to go near the river when the Sibeye Boys (young thugs), with their guns, are out on patrol, or beyond certain areas of the forest, where heavily armed rebels may be hanging out, planning attacks on pipelines and on those who work for oil companies. Explosions, deaths, and kidnappings for ransom have become common.

As the lives of the Kentabe family unfold, the reader observes how they try to cope with rivers so polluted they cannot use the water, air that no one should have to breathe, trees and crops that will no longer grow in the soil, jobs that are given to foreigners and those with close ties to the government, poverty due to corruption of government officials, and the greed of the oil companies, most of them run by Americans. This pollution of the land, rivers, and air has continued unabated for over fifty years. As it continues to get worse, we see here, young Nigerians are organizing to seize “their heritage”–the oil under their land. Violence has become endemic. Blessing and Ezekiel are warned not to go near the river when the Sibeye Boys (young thugs), with their guns, are out on patrol, or beyond certain areas of the forest, where heavily armed rebels may be hanging out, planning attacks on pipelines and on those who work for oil companies. Explosions, deaths, and kidnappings for ransom have become common.

Though the novel starts slowly, with its emphasis on developing character and setting, it becomes, eventually, a series of interconnected episodes which illustrate the problems of the country, as Blessing, Ezekiel, and their mother Timi try to find happiness in their new life. When Timi, the mother, finds a new suitor, Ezekiel becomes an angry teenager and acts out in ways that no one has ever seen before, precipitating a crisis.

Though the novel starts slowly, with its emphasis on developing character and setting, it becomes, eventually, a series of interconnected episodes which illustrate the problems of the country, as Blessing, Ezekiel, and their mother Timi try to find happiness in their new life. When Timi, the mother, finds a new suitor, Ezekiel becomes an angry teenager and acts out in ways that no one has ever seen before, precipitating a crisis.

The author’s style is simple, straightforward, and easy to digest, with much of the action being conveyed through dialogue. The author gives the reader everything s/he needs in order to imagine what is happening, rather than requiring a reader to “stretch” or fill in blanks. While this may sacrifice suspense and make the novel unusually episodic, the totally engaging characters are well drawn and keep the interest high. A book that deserves its place on CNN’s list of “Twelve Novels to Keep You Entertained All Summer.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.otherpress.com

Like Blessing and her family, two boys are drawing water from the polluted river:

Armed young men, some still boys, in a gunboat along the river: http://www.thedailymaverick.co.za

An oil fire threatens a small village nearby: http://sherpas2.blogs.sapo.pt

The Tiny Sunbird, similar to a hummingbird, was photographed by Nik Borrow: http://www.birdquest-tours.com