“Don’t be expecting any big flowery longwinded poetic picturesque horseshit passages in this book explaining the look of something. If I have to go into that much detail I’ll take a photograph or draw a picture. This is for people like myself who hate reading.”

Charlie McCarthy, who is twenty-five as the book begins, is writing about events which occurred five years ago in Ballyronan, outside of Cork, events so traumatic for him that he is still suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. And that’s on top of his problems as a “Gamal,” short for Gamallogue, an Irish word for someone who is “different” – not someone who is developmentally limited in the usual sense but someone, like Charlie, who seems to do everything wrong – unintentionally wearing his shirt back to front, forgetting to wear his socks, spilling his Lucozade on his shirt in the pub, and saying the wrong things at funerals. For two years “after the things that happened,” he says, he was unable to do anything at all. “I just was.” The reader knows from the opening paragraph that Charlie’s trauma involved two lovers, his friends Sinead and James, and his early descriptions of Sinead in the past tense lets us know from the outset that she has died. We know nothing else, however, nor do we know much about James, at that point, except that he and Sinead were Charlie’s only friends in a school atmosphere in which bullying was common.

Charlie McCarthy, who is twenty-five as the book begins, is writing about events which occurred five years ago in Ballyronan, outside of Cork, events so traumatic for him that he is still suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. And that’s on top of his problems as a “Gamal,” short for Gamallogue, an Irish word for someone who is “different” – not someone who is developmentally limited in the usual sense but someone, like Charlie, who seems to do everything wrong – unintentionally wearing his shirt back to front, forgetting to wear his socks, spilling his Lucozade on his shirt in the pub, and saying the wrong things at funerals. For two years “after the things that happened,” he says, he was unable to do anything at all. “I just was.” The reader knows from the opening paragraph that Charlie’s trauma involved two lovers, his friends Sinead and James, and his early descriptions of Sinead in the past tense lets us know from the outset that she has died. We know nothing else, however, nor do we know much about James, at that point, except that he and Sinead were Charlie’s only friends in a school atmosphere in which bullying was common.

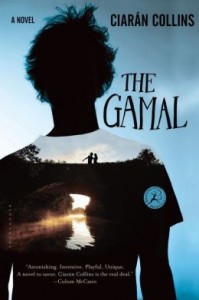

Charlie’s “main shrink” has persuaded him to write a thousand words a day about his life, and he has agreed, reluctantly, telling his reader that “You won’t like me. Mainly because you know I don’t care whether you like me or not, and people don’t like that, do they? They might say they do but they don’t. Saying means nothing cos it could just as well be lies.” Inserting drawings instead of bothering to describe people and places, Charlie begins his book – this book – also including passages from psychology textbooks, dictionaries, and eventually court transcripts. Since he loves music, and Sinead and James were teenage folk musicians, he had hoped to include the words to particular songs, but he does not want to pay royalties, so he names the songs and the singers and leaves spaces for the reader to insert the lyrics. When he updates the reader on how many words he has written, Dr. Quinn demands he pay attention to his task and stop delaying, and he finally writes that five years ago he was a witness in a court case in criminal court and that it went on for four weeks. He can remember virtually every word that took place, with a kind of audio memory that he says is akin to the photographic memory associated with sight. The case involved Sinead and her death.

Carrigadrohid, a castle near Cork, similar to the one that the Kent family restored. Photo by Mike Searle

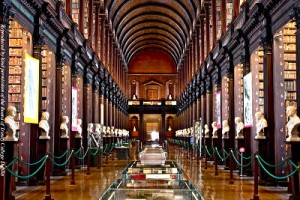

Slowly, through flashbacks, Charlie reveals information about his life, Sinead’s, and James’s, though Dr. Quinn also requires him to include other characters who are “secondary” characters, especially Dinky, Teesh, Snoozie, and Racey, all of whom he refuses to discuss for much of the book. The reader learns that Sinead, in addition to having a beautiful voice, is also an artist, and Charlie reveals that she is planning to go to an art college in Dublin after graduation from secondary school. Her family has very little money, lives in a council house, and her father is “the meanest alcoholic in Europe.” James is planning to attend Trinity in Dublin. The son of a wealthy Protestant who has moved with his family to Ballyronan after purchasing and restoring an old castle, James is not only intelligent but is also an outstanding athlete, able to play any sport, something that does not endear him to the locals when he becomes the best player on their Gaelic football team. Charlie lives with his hard-working parents who are often harsh with him, and he is often bullied at school, even by his primary school teachers. He first became friends with Sinead, in fact, when she stood up for him against a teacher who was insulting him. As soon as Sinead meets James, however, the two become inseparable, though they continue to include Charlie in their lives and activities.

Library at Trinity College, where the Book of Kells is one of more than five million volumes. This is where James started college.

Gradually, all the characterizations develop with substantial detail, and Charlie’s attitudes toward various people add color to the action. His special vernacular makes the prose fun to read, and when Dr. Quinn suggests that Charlie’s story might be better if he included similes, his response – five pages of similes – is hilarious, including the unique observation that “similes are like empty retches between vomits.”

For the first hundred pages, however, the reader knows almost nothing about the mysterious tragedy of Sinead and James, even as Charlie makes remarks like “Sometimes I think I’m like the cameraman who let it happen. Other times I know I’m not. I didn’t let nothing happen. And I did nothing. I know it.” The reader still has little idea what the “it” is, other than the one or more deaths which have been known since the opening page, nor does s/he know how “it” happened, a long time for a reader to wait for crucial details, especially with all the foreshadowing beginning on page one. Through transcripts of testimony given by secondary characters, the reader very gradually learns more about Sinead’s death and its all-encompassing aftermath, but it is impossible to know whether the testimony is the truth and what these characters might gain if they lied. Snippets of the story are revealed, initially, with little context, creating still more foreshadowing but little sense of the overriding tragedy until well past the halfway mark of this nearly five-hundred-page book. At that point, however, the novel makes up for lost time. The characterizations, especially those of the secondary characters, make the nastiness which occurs among these school “friends,” and which leads to a terrible death, that much more dramatic and affecting.

Debut novelist Ciaran Collins, a teacher living in Kinsale, has a fine sense of the dynamics of a small town and of the long-term effects of trauma on a character like Charlie. His characters, some of them loathsome, never veer far from the meanness everyone has seen among young, small-town bullies, and his sense of a grand, horrific climax is daunting. What takes this novel beyond narrative gamesmanship is the pervading sense that no one can be trusted, and at the conclusion, still more revelations gradually dawn on the reader. Though the novel does have some problems with pacing at the beginning, Collins’s control of his story is absolute, and readers are in for a treat with his characterizations.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.smh.com.au

Carrigadrohid, the small castle pictured here, similar, perhaps, to the one that the Kent family restored, is by Mike Searle and is seen on http://www.geograph.org.uk/ , reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Licence.

The Library at Trinity College, Dublin, which James attended, contains over five million volumes, including the Book of Kells.

The Copper Beech tree, is one of the world’s most beautiful and symmetrical trees. It plays a role in the concluding section of the novel: photoadayfor2010.wordpress.com

ARC: Bloomsbury