“We women worry, all of us, about everything – especially marriage. After all, what was there more important than that? She could have looked back – from a nursery filled by their own, dear children – and seen that moment [of ancient doubt] as a nothing. As one small, private stumble on the rosy path to conjugal felicity. But life had not done that. It had robbed her and, in so doing, snatched away any presumption of innocence.” – Cassandra Austen, 1840.

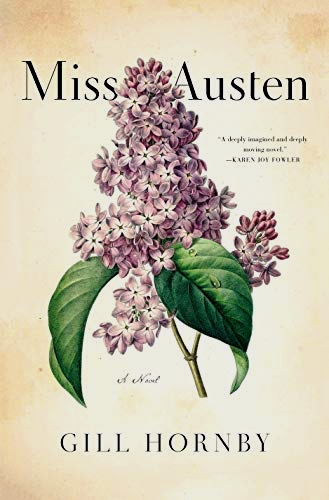

Although much-loved author Jane Austen is a dominating force throughout this biographical novel by Gill Hornby, most of the action here revolves around Jane’s older sister Cassandra.

Although much-loved author Jane Austen is a dominating force throughout this biographical novel by Gill Hornby, most of the action here revolves around Jane’s older sister Cassandra.

Closer to Jane than any other family member or friend, Cassandra is privy to every aspect of Jane’s life, living with her and sharing most of her life, including Jane’s final illness when Jane is forty-one. Part of a large family of eight children, born to the Rector of Steventon, Rev. George Austen and his wife, the Austen sisters, who are three years apart, have six brothers, their closest friends being the children of other nearby clergy, including the family of the Vicar of Kintbury, Thomas Fowle. Miss Austen author Gill Hornby, herself, also lives in Kintbury, and she has clearly absorbed the chronicles of Jane Austen and her family as part of her daily life.

Having previously written The Story of Jane Austen, a biography for young readers, Hornby has obviously “lived with” Jane Austen so intimately, over the years, that readers of this novel may be surprised to learn that the revelatory letters here, purportedly written by Jane Austen or her family, were, in fact, written by author Gill Hornby herself. Through them, she provides insights into the lives of both Cassandra and Jane, and her vibrant details of everyday life bring the society of the era to life. More importantly, however, the author recreates some of the psychological issues with which these women had to contend whenever fate unexpectedly changed their social positions through death, loss of home, or loss of income. By highlighting these issues within fictional letters, Gill Hornby offers insights into social conflicts faced by women and makes them understandable to modern readers – no matter how much the reader might regret some of the actions these characters take to resolve their problems.

The novel opens with the marriage proposal of Thomas Fowle, a young parson who is the son of the Vicar of Kintbury, to Cassandra Austen in 1795, a proposal that “had been settled as a public fact long before it was decided by the couple in private.” For Cassandra, “This was her destiny. Her life was in place,” but she and Tom both know that the engagement will be a long one, as Tom cannot afford a bride right now. The next chapter takes place at Kintbury in 1840, half a century later, as Cassandra joins Tom’s three sisters to clear out the rectory for a new vicar. “For the family – and most especially for its single women – to leave a vicarage was to be cast out of Eden. There were only trial and privation ahead.” As she helps with the clearing out, Cassandra has only one purpose: She intends to find all of her deceased sister Jane’s extant correspondence and discard anything that is extremely personal or reflects badly on Jane or her legacy. Some letters are found – and hidden under the mattress by Cassandra – till she can get them back home. Again, time and place shift back to Steventon, the rectory where the Austens lived in 1795, allowing the social complications of the love story between Cass and Tom to develop a bit as Cass is invited to spend Christmas with the Fowle family, her future in-laws. Tom, however, has just been invited to spend a year accompanying Lord Craven as his private pastor on a trip to the Windward Isles in the West Indies. He has accepted because the fee is high enough to speed up his marriage to Cass, but he must leave in two weeks.

In another shift back to Kintbury in 1840, revelatory documents found by Cass include more letters from Jane, letters about the death of Cass’s fiancé, information about at least one serious suitor for Jane, and a potential new courtship for Cass. As the time frame continues to move back and forth between the late 1790s and the mid-1800s, the reader sees how fragile, but stubborn, Jane Austen is, especially when their father’s death decimates the finances of Jane, Cass, and their mother. More personal, enlightening letters continue up through 1807, illustrating Jane’s depression and the family’s worries about where the unmarried Jane and Cass, along with their mother, will reside. After living with a variety of family and friends for various lengths of time over several years, they eventually get their own residence at Chawton. “Adopted by wealthy relations in his youth,” and now “living the life of a landed gentleman,” Edward, brother of Jane and Cass, suggests that they move to one of the cottages on his inherited estate, and, in 1809, they do. From 1810 – 1817, the year of Jane’s death, Jane Austen writes and publishes six novels to growing popular acclaim, though they are published only by “A Lady,” and bring in no income: Sense and Sensibility (1810), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1815), Northanger Abbey (1817), and Persuasion (1817), the latter two published posthumously.*

Author Gill Hornby, whose concern with sociological issues is immense, is also a consummate novelist, alternating her time frames to show how issues are resolved or not, developing a consistent set of characters from just three interconnected and often intermarried families, and showing that the Austen women are not unique in the problems they face. She is also aware of the need for human “villains,” or in this case, villainesses, to provide variety in the narrative’s action. The first such character is Dinah, a maid who lives by her own rules and who does not hesitate to interfere, if she thinks she will not be caught. The second, more fully developed villainess, is Mary Lloyd, a woman of limited attractiveness but enormous ambition, who marries James Austen, the rector of Steventon, the brother of Cass and Jane. Mary sees herself as the grande dame of the family, the one who rules – and believes that she deserves to rule – in her own favor throughout her marriage. It is not until Cass finds the last batch of letters that the true horrors of Mary’s interference become known. By this time, the reader is so involved in the story that it is easy to forget the actual source of all these letters. Filled with information that reflects the lengthy research the author has done into the lives of Jane and Cass Austen, beautifully constructed, and lively to read, Miss Austen is a significant addition to the world of Jane and Cass Austen and all the mysteries still associated with them.

*Note: LADY SUSAN, written when Jane Austen was a teenager and not included among her Big Six novels, was not published until 1871, but it is widely regarded as her wittiest and most playful novel.

Click to enlarge. This elaborate plaque in Winchester Cathedral, where Jane was buried, celebrates her life. Photo by Ian G Dagnall.PHOTOSPhotos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.edbookfest.co.uk

PHOTOS: Steventon, the Vicarage of Rev. George Austen, Jane and Cass’s father, is shown in this drawing. https://www.janeausten.co.uk

A cottage at Chawton House, owned by Cass and Jane’s brother, is where Jane lived with Cass for the last nine years of her life: https://www.viator.com/tours

Cass is the artist responsible for this drawing of Jane, the one portrait which is the basis of all known portraits of Jane Austen. http://elizabethberkeleycraven.blogspot.com

Jane was buried in the nave of Winchester Cathedral, with this plaque on the wall to celebrate her life. As she was almost unknown at the time of her death, only a small reference is made to her writing. Photo by Ian G. Dagnall. https://www.alamy.com