Note: This book was WINNER of the prestigious M-Net Book Prize and WINNER of the Old Mutual Literary Prize in South Africa.

“As she entered [the snooker room], Karolina felt the hair along her spine and the back of her neck stand on end. A room filled with strange vibrations, a place where one could go mad and commit a crime, where one could lose one’s head and one’s good judgement, and be at the mercy of the collusions of one’s neighbour as well as one’s own unfathomable drives. A place that might unexpectedly activate the links in a chain of old memories. A congenial place, cosy.”

The sardonic comment at the end of this quotation says all that needs to be said in establishing the tone of Voorspoed, a small rural “dorp” in the center of South Africa in 1994, which is the setting of this novel. A whole new way of life has just begun for the residents, both black and white, since white rule has just been abolished with the election of Nelson Mandela as the new President of the country. The long conflict between the British and the Boers, both of which sought dominion over the blacks generations ago, has been officially resolved for years, but eighty percent of the country’s residents, its blacks, are still poor and still have little to say as far as the government is concerned. In this novel from 1994, the tensions and the uncertainty are palpable, but they remain constantly in the background of the novel and only rarely intrude on the action surrounding the main character. Newly translated into English by Iris Gouws and author Ingrid Winterbach, The Elusive Moth captures a unique period in a small rural community in which no one can be quite sure who is really in charge. Whoever thought he was in charge, especially among the police, made sure that everyone else knew it, whether or not it was true.

The sardonic comment at the end of this quotation says all that needs to be said in establishing the tone of Voorspoed, a small rural “dorp” in the center of South Africa in 1994, which is the setting of this novel. A whole new way of life has just begun for the residents, both black and white, since white rule has just been abolished with the election of Nelson Mandela as the new President of the country. The long conflict between the British and the Boers, both of which sought dominion over the blacks generations ago, has been officially resolved for years, but eighty percent of the country’s residents, its blacks, are still poor and still have little to say as far as the government is concerned. In this novel from 1994, the tensions and the uncertainty are palpable, but they remain constantly in the background of the novel and only rarely intrude on the action surrounding the main character. Newly translated into English by Iris Gouws and author Ingrid Winterbach, The Elusive Moth captures a unique period in a small rural community in which no one can be quite sure who is really in charge. Whoever thought he was in charge, especially among the police, made sure that everyone else knew it, whether or not it was true.

Karolina Ferreira, an entomologist who is searching for a rare moth, arrives in Voorspoed, where she summered twenty five years ago with her family, and it is her current experiences in 1994 that drive this character-based novel. Her father, from whom she became alienated before his death, was also an entomologist. With her parents dead and her sister far away studying geology in the Arctic, Karolina is alone. She hikes through the veld each day with Basil September, a botanist, also new to town, who is seeking unusual plants for possible use as new cures for diseases, but Karolina herself, like the country, is at loose ends. “She had long withdrawn from this place, there was nothing here to which she might attach herself now.” She no longer knew anyone, and many of the familiar buildings were gone. “There was a different feel to it now.”

Hebdomophruda complicatrix, one of a dozen similar moths of this genus. The Hebdomophruda crenilinea, Karolina's goal, is not shown anywhere on the internet.

Gradually, she comes to know some of the town’s characters, depending on Basil for insights into some of them – and Basil doesn’t hold back, appearing to have an almost extrasensory perception of who they “really” are. Regarding the magistrate, he tells Karolina that “he pisses a forked green stream…probably rejected by his mother at an early age, unquenchable thirst…Malicious. Manipulative.” He describes Captain Gert Els, who frightens Karolina when he makes overtures to her as she heads for the ladies’ room, as “a man who finds it hard to restrain himself.” Lt. Kieliemann, who also tries to intercept her in the hallway, is “of schizoid disposition [with] a tendency towards fetishism…Cool exterior, burning interior, excessive sexual fantasies.” As for his evaluations of character, Basil believes that anyone can do it. The ironies of all these absolute statements seem to escape both Basil and Karolina.

Karolina is fascinated by the paintings in the dining room at the hotel where she lives, one of which is of the Battle of Ladysmith, in which the British liberated the besieged town of Ladysmith after almost four months.

Using the hotel bar and snooker room as the town’s central gathering place, Karolina meets many men (like moths to a flame?) but few women. She does observe lovers having illicit affairs, and she enjoys dancing every Saturday night with one man with whom she rarely even talks. Over time, their dancing gradually becomes more and more frantic, until eventually she experiences a kind of dance-induced euphoria. “She no longer expected immediate gratification. The study of moths and the refinement of her dance technique, these were the objects of her passion. She expected nothing at all from any man, woman, or lover.” In the meantime, she still has nightly dreams of the past, many of them sexual, and it is not until later in the novel that she begins to feel signs of real love.

Karolina's lover has a Tibetan tanka on the wall of his room, celebrating the eastern view of death and reconciliation.

Karolina’s search for her moth is focused on what for hundreds of years was its natural habitat but which is now a dry, dusty plain with almost no vegetation left, the result of the wars between Boers and British, a hundred years ago, and the burnings that took place on the veld. Though the reader recognizes the symbolism of Karolina’s search, she herself seems not to notice. “The moths are elusive. That’s why they’re so good at surviving in extreme conditions,” she remarks, seeing no parallels to her own life. She continues to experience nightmares and dreams of death, some of them undoubtedly induced by violent events in Voorspoed, and related to the changing political scene. Accidents which may not be accidents, murder, suicide, and racial crimes all appear as the novel develops, and while the reader may be horrified, as the author undoubtedly intended, Karolina remains relatively insulated from the horrors. The town breathed “not a word to give any indication that things were constantly brewing underneath the surface,” as Karolina slowly develops her own sense of self.

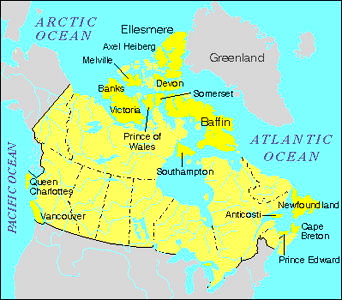

Late in the novel, Karolina has contact with her sister, whose research is on Victoria Island, near Banks Island, in the Beaufort Sea. Double click to enlarge.

As in her two later novels available in English, To Hell with Cronje, and The Book of Happenstance, Winterbach deals with clear themes of life, love, and death, analyzed on a grand scale and shown in an equally grand evolutionary context. Her concern with her characters’ places in the world is not frivolous, not simply a literary conceit chosen to allow her to give “significance” to her story. In all her novels, she shows a total commitment to big ideas on a big scale and organizes them in such a way as to enhance the story, not overpower it. Powerful and dramatic, her novels may deal with major events, such as the Boer War in To Hell with Cronje (which I regard as one of the best war novels ever written), or with smaller events, such as we see here, in which the focus is on the inner life of a main character at a crossroads in his/her life. Though there are times in this novel in which the philosophizing and the allegorical connotations may begin to overpower the story, Winterbach aims high, a goal to be celebrated even if it occasionally overshoots its mark. An unusual novel set during a unique time in the history of South Africa.

Also by Ingrid Winterbach: TO HELL WITH CRONJE and THE BOOK OF HAPPENSTANCE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://nb.bookslive.co.za

Karolina’s moth, Hebdomophruda crenilinea, is not pictured anywhere on-line, that I could find, though a dozen other genus Hemophruda are. All resemble this Hebdomophruda complicatrix in the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology. http://www.boldsystems.org

G. W. Bacon’s print of the British liberating Ladysmith after four months of siege is found on http://angloboerwarmuseum.com

The Tibetan tanka about death, which Karolina’s lover has on his wall, may be found on http://wallpaperpanda.com/

Karolina’s sister does research on stones on Victoria Island, in the Beaufort Sea, Arctic Circle. Double click on the map to enlarge it. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

ARC: Open Letter Books