Note: Published as L’Ogre in France and newly republished in the US by Bitter Lemon Press, this novel was WINNER of the Prix Goncourt in 1973.

“My God, what have I done that You take everything from me? I’m wrapped up in myself, separated from the others, deprived, guilty, because of Your Law, which I submit to like a humiliated child. Will the barrier fall? Will sweetness be given to me, rendered up to me…?”

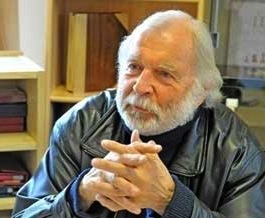

An author revered as much for the controlled lyricism of his prose as for his uncompromising characterizations, Swiss author Jacques Chessex (1934 – 2009) was the first foreign citizen to win the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary award. In this dramatic novel from 1973, he tells the story of Jean Calmet, a thirty-eight-year-old schoolteacher, whose physician father has just died and with whom he has had a fraught relationship. The youngest of five children, Jean both loved and feared his father, with good reason, and he is glad that his father has been cremated, rather than buried. “The doctor would be reduced to ashes. He could not be allowed any chance of keeping his exasperating, scandalous vigour in the fertile earth,” Jean thinks. “Make a little heap of ashes of him, ashes at the bottom of an urn. Like sand. Anonymous, mute dust.”

An author revered as much for the controlled lyricism of his prose as for his uncompromising characterizations, Swiss author Jacques Chessex (1934 – 2009) was the first foreign citizen to win the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary award. In this dramatic novel from 1973, he tells the story of Jean Calmet, a thirty-eight-year-old schoolteacher, whose physician father has just died and with whom he has had a fraught relationship. The youngest of five children, Jean both loved and feared his father, with good reason, and he is glad that his father has been cremated, rather than buried. “The doctor would be reduced to ashes. He could not be allowed any chance of keeping his exasperating, scandalous vigour in the fertile earth,” Jean thinks. “Make a little heap of ashes of him, ashes at the bottom of an urn. Like sand. Anonymous, mute dust.”

As the family gathers to choose an urn, Jean meditates on his father’s relationships with the whole family. His meek mother has lived for fifty years “under the weight of the doctor’s shouts, orders….bent under the tyrant, broken, destroyed.” His brothers and sisters have gone on to lives of their own and do not return home often, while he, “the Benjamin,” the Biblical youngest and best-loved son, is unmarried and lonely, though no longer living at home. His job as a teacher provides him with a “refuge from the authority of that father who is bearing down with all his weight on the rest of the world,” but he has few friends, and though he mentors his students, he is emotionally much like them, still in the thrall of a domineering parent. He recognizes that “At all costs he must avoid having his father’s urn remain at Les Peuples (at the family home). It had to be locked up far from here, imprisoned behind a solid iron gate, one that was permanent.”

The Morbier Clock in the dining room is seen as a “tall coffin”

Death soon becomes Jean’s constant companion. One of his students, Isabelle, is dying of cancer but refuses to give in, insisting on living every minute of her remaining life, sketching, writing poems, and visiting with friends. By contrast, Jean is obsessing about death, seeing ghosts of his father, and even seeing a porcupine as a symbol of a “wild, happy freedom” which he cannot feel. He thinks about the fire in the crematorium as a “beautiful purifier,” even as he is dwelling on moments in which his father has yelled at him for being a “cringing, muddleheaded weakling.” He thinks of the monument to Sire Francois at the Jacquemart Chapel, 1362, one that is covered with snakes and toads. Thoughts of sex get confused with death, as he remembers seeing his father in a relationship which he should never have seen, and he is unsuccessful in his own relationships. With no emotional resources to sustain him, even by the age of thirty-eight, he is a completely lost soul, someone ready to become a victim of others, if not himself.

Jacquemart Chapel, 1362, with statue covered with snakes and toads.

When student demonstrations take place at Jean’s school, there is an element of excitement and camaraderie, a shared commitment which gives purpose to the lives of some of his students in ways that Jean himself has never known, and when he takes a group of them on a school trip to Bern, his observations are quite different from theirs. The “Ogre Fountain” and the Bear Pits, regarded as sightseeing destinations for the students, take on ominous symbolic meanings for Jean. The symbols of a cat, a rat, and a coin add to the heavy sense of his own oppression.

In an age in which TV, the internet, and social networking are ubiquitous, it is difficult to identify fully with someone who feels as isolated – and, more importantly, as helpless – as Jean Calmet. I found myself becoming a bit impatient with this thirty-eight-year-old man who has more in common with his students than with the adult world, and as he becomes more and more obsessed with his own problems and less connected with the outside world (if that is possible, considering his record of inaction), I had a hard time identifying with him in the way that his readers from 1973 must have done. And when he makes the statement with which I begin this review, “My God, what have I done that You take everything from me? I’m wrapped up in myself, separated from the others, deprived, guilty, because of Your Law,” it is easy to see that whether he is blaming God or his father, whom he often sees as the same, he is accepting no responsibility for choices he has made on his own. Though his father is clumsy and crude, he has tried to reach out in his own way to the son he cannot begin to understand, and Jean’s four siblings have managed to escape his father’s complete domination. One has to wonder how much the author expects us to identify with Jean, who rationalizes that “he had remained in his father’s power, and he had been murdered.”

Bear Pit, Bern, with bears begging for their food, another symbol for Jacques

The glories of nature, lyrically described, add to the depth of this novel, and one would think they would be comforting to Jean, whose aesthetic sensibilities are finely honed. Unfortunately, any beauty Jean sees seems to vanish as he contemplates death as a destroyer. His personal neediness overwhelms any sense of perspective that he may have, as his meeting with George Mollendruz shows near the end of the book. When, late in the novel, he sees a dead animal, he observes that “One is not safe being independent in our part of the world. Not safe staying wild and uncompromising in the city,” offering yet another observation about his own inaction (though he himself could hardly be considered “wild and uncompromising”). Ultimately, I found this novel a fascinating set piece about life in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Now, forty years after this novel was written, it would be much more difficult to feel as isolated, lonely, and hopeless as Jean Calmet does, and readers now may have more trouble identifying with the main character of this intense psychological novel.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.espaceculturel.ch

One image with which Jean always identifies his father and his home is the Morbier clock, “tall as a coffin,” that dominates the dining room. From http://duetime.wordpress.com

When Jean has a loss of control, at one point, he imagines the Jacquemart Chapel, 1362, in which the statue of the deceased is covered in snakes and toads. (That is difficult to see here, but one snake is on the upper arm, and more are on the legs, obvious symbols.) http://www.lake-geneva-region.ch

The school trip to Bern features a visit to the “Ogre Fountain.” See http://www.dicconbewes.com

The Bear Pits of Bern, a tourist attraction, feature bears begging for their food from deep inside their prison. http://www.gourmantic.com – yet another symbol for Jacques’s life.