Note: Jane Gardam is WINNER of the Heywood Hill Literary Prize for a lifetime’s contribution to the enjoyment of literature. She is also the only author to have been a two-time WINNER of the Whitbread Award.

“Suppose I had stayed [in rural northeast England]—like my mother. [Imagine] a sort of castaway girl who lived there all her life like Robinson Crusoe. I’d give her a library—her dead grandfather’s vicarage books…I’d give her knowledge of the heart’s affections. And I’d show the power of her childhood landscape, the enfolding murmuring magical marsh so flooded with light sunshine, silvery rain and mist, and the running sea.” – Jane Gardam, Preface, 2011.

In the introduction to this re-publication of Crusoe’s Daughter (1986), author Jane Gardam admits that “This [is] by far the favourite of all my books.” Brought up in near isolation in the rural north of England, like the main character of this novel, Gardam herself eventually escaped to college in London, but though she joined London’s academic world and had great success as a novelist, she admits “It was the elf-light of childhood that still hung about, the wonder of the marsh…the people still more real to me in the vanished place than most of the people I’ve met since.” Her mother remained in the rural north for her whole life, and Gardam uses her mother’s life as the starting point of this novel, setting it at the turn of the twentieth century on the northeast coast (in or near North Yorkshire and Northumberland, judging from her geographical clues). Though Polly Flint differs in significant ways from her mother, as Gardam explains in the Preface, she admits that when she finished the novel, “I felt I needn’t write any more books. Take it or leave it, Crusoe’s Daughter says everything I have to say.” Fortunately for us, she did write additional highly successful novels, but this one, her favorite, is the most poignant, told with an honesty and affection for her setting that her dryly humorous, more satiric novels lack, however wonderful they are in their own right.

In the introduction to this re-publication of Crusoe’s Daughter (1986), author Jane Gardam admits that “This [is] by far the favourite of all my books.” Brought up in near isolation in the rural north of England, like the main character of this novel, Gardam herself eventually escaped to college in London, but though she joined London’s academic world and had great success as a novelist, she admits “It was the elf-light of childhood that still hung about, the wonder of the marsh…the people still more real to me in the vanished place than most of the people I’ve met since.” Her mother remained in the rural north for her whole life, and Gardam uses her mother’s life as the starting point of this novel, setting it at the turn of the twentieth century on the northeast coast (in or near North Yorkshire and Northumberland, judging from her geographical clues). Though Polly Flint differs in significant ways from her mother, as Gardam explains in the Preface, she admits that when she finished the novel, “I felt I needn’t write any more books. Take it or leave it, Crusoe’s Daughter says everything I have to say.” Fortunately for us, she did write additional highly successful novels, but this one, her favorite, is the most poignant, told with an honesty and affection for her setting that her dryly humorous, more satiric novels lack, however wonderful they are in their own right.

As the novel opens at the beginning of the twentieth century, five-year-old Polly Flint and her father arrive at Oversands, a big yellow house on England’s wild northeast coast, by the river Tyne. Her father, a sailor whose wife died when Polly was an infant, had left her with a series of foster mothers in Wales during her first five years, and his visit with Polly to the home of his wife’s older, unmarried sisters is completely unexpected by those quiet ladies. Shortly after arriving at Oversands, Polly’s father dies, leaving her to be brought up by her Aunts Mary and Frances in a place so isolated that there are virtually no other children. Though she likes her aunts and is particularly fond of her Aunt Frances, she admits that “I would not have known what to do with love if it had been offered.” There is no school she can attend, but she is bright and curious, and she quickly learns to read from her aunts. Through the unpleasant Mrs. Woods, who also lives at Oversands, she also learns French and German. Every day is predictable, however, and the same people come to the house for the same purposes every week.

As the novel opens at the beginning of the twentieth century, five-year-old Polly Flint and her father arrive at Oversands, a big yellow house on England’s wild northeast coast, by the river Tyne. Her father, a sailor whose wife died when Polly was an infant, had left her with a series of foster mothers in Wales during her first five years, and his visit with Polly to the home of his wife’s older, unmarried sisters is completely unexpected by those quiet ladies. Shortly after arriving at Oversands, Polly’s father dies, leaving her to be brought up by her Aunts Mary and Frances in a place so isolated that there are virtually no other children. Though she likes her aunts and is particularly fond of her Aunt Frances, she admits that “I would not have known what to do with love if it had been offered.” There is no school she can attend, but she is bright and curious, and she quickly learns to read from her aunts. Through the unpleasant Mrs. Woods, who also lives at Oversands, she also learns French and German. Every day is predictable, however, and the same people come to the house for the same purposes every week.

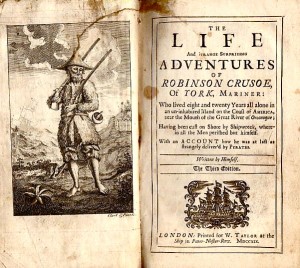

In her loneliness Polly finds her greatest solace from the books in the library of the house, especially when she discovers Robinson Crusoe, whose twenty-eight-year isolation on an island offers her a way of dealing with her own isolation. Crusoe, an obviously pragmatic man who must deal with each day as it comes, relies on his own ingenuity to solve his problems, just as Polly knows she will have to do. Her first real conflict with the aunts comes when she is twelve, as she firmly rejects being Confirmed in the church, refuses the idea of communion, and criticizes the church’s large wooden crucifix with carved blood dripping from it. Her aunts’ religiosity cannot stand up to Robinson Crusoe’s realism for Polly. “I’m young and I’m empty of life. I just am,” she cries. “I can’t ever forget myself and how I have to be. All the hymn-words spring up and the Collects, Creeds, and Epistles. There doesn’t seem to be anything else.”

In her loneliness Polly finds her greatest solace from the books in the library of the house, especially when she discovers Robinson Crusoe, whose twenty-eight-year isolation on an island offers her a way of dealing with her own isolation. Crusoe, an obviously pragmatic man who must deal with each day as it comes, relies on his own ingenuity to solve his problems, just as Polly knows she will have to do. Her first real conflict with the aunts comes when she is twelve, as she firmly rejects being Confirmed in the church, refuses the idea of communion, and criticizes the church’s large wooden crucifix with carved blood dripping from it. Her aunts’ religiosity cannot stand up to Robinson Crusoe’s realism for Polly. “I’m young and I’m empty of life. I just am,” she cries. “I can’t ever forget myself and how I have to be. All the hymn-words spring up and the Collects, Creeds, and Epistles. There doesn’t seem to be anything else.”

Love and death eventually complicate life at Oversands, and in her teens Polly goes to stay with elderly family members, Arthur Thwaite and his sister Celia, who live on the Yorkshire moors, some distance away. Their house, an artists’ retreat, expands her vision of life dramatically, though she is not sure if it is a madhouse, a hospital, or a private asylum. Poets, writers, and musicians, some of them failed, provide a totally different kind of life for Polly, the other extreme from what she has known, leading Polly to tell her Aunt Frances in a letter that “I don’t believe I shall ever fit in anywhere.” A few friendships and one or two romantic crushes give Polly’s life a semblance of normalcy as she matures to her twenties, but as the novel continues to progress up to the 1980s, two world wars, industrialization, and population growth create chaos even in the rural countryside.

Gardam creates real atmosphere here in both time and place, and rural northeast England becomes almost a character of its own, a place filled with wild beauty, harsh weather, and untamed landscapes. The novel’s realism keeps Polly’s story from becoming a romance, however much the reader may empathize with her, and the author’s honest feelings for her characters, many of them based, in part, on her own family members, endow the novel with a poignancy that one does not often find elsewhere in Gardam’s novels. The Robinson Crusoe leitmotif is well integrated, running throughout the novel over the course of more than eighty years, and it firmly connects all aspects of the novel’s long chronology. A delightful “conversation” between Polly and Crusoe on the nature of fiction, late in the novel, is one of Gardam’s classics. “[Fiction] will have to change,” Polly tells Crusoe. “It’s become quite boring – all about politics or marital discord. The minutiae. You should see the fiction they have thought up about you and Friday.” To which Crusoe replies, “Yes, well, he could be very trying.” The novel’s final pages, as close to a grand finale as Gardam will probably ever get, will leave a smile on the face of every reader – filled as it is with the dry wit and sense of dramatic irony for which Gardam is so famous, a perfect ending to one of her warmest and most enjoyable novels.

Gardam creates real atmosphere here in both time and place, and rural northeast England becomes almost a character of its own, a place filled with wild beauty, harsh weather, and untamed landscapes. The novel’s realism keeps Polly’s story from becoming a romance, however much the reader may empathize with her, and the author’s honest feelings for her characters, many of them based, in part, on her own family members, endow the novel with a poignancy that one does not often find elsewhere in Gardam’s novels. The Robinson Crusoe leitmotif is well integrated, running throughout the novel over the course of more than eighty years, and it firmly connects all aspects of the novel’s long chronology. A delightful “conversation” between Polly and Crusoe on the nature of fiction, late in the novel, is one of Gardam’s classics. “[Fiction] will have to change,” Polly tells Crusoe. “It’s become quite boring – all about politics or marital discord. The minutiae. You should see the fiction they have thought up about you and Friday.” To which Crusoe replies, “Yes, well, he could be very trying.” The novel’s final pages, as close to a grand finale as Gardam will probably ever get, will leave a smile on the face of every reader – filled as it is with the dry wit and sense of dramatic irony for which Gardam is so famous, a perfect ending to one of her warmest and most enjoyable novels.

ALSO by Gardam: GOD ON THE ROCKS, QUEEN OF THE TAMBOURINE, THE PEOPLE ON PRIVILEGE HILL, A LONG WAY FROM VERONA OLD FILTH, THE MAN WITH THE WOODEN HAT, LAST FRIENDS, THE FLIGHTS OF THE MAIDENS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Eamonn McCabe appears on http://www.guardian.co.uk

The photo of a yellow house in South Shields, on the Northumberland coast by the river Tyne, is by demonsub and appears on http://www.flickr.com

The untamed moors leading to the ocean are shown on http://www.enjoyengland.com

An old edition of Robinson Crusoe appears on http://imaginactory.com

ARC: Europa