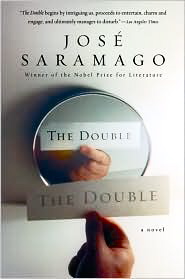

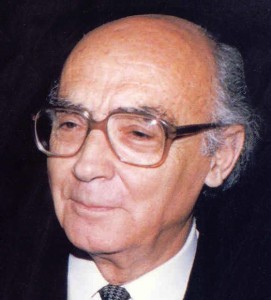

Note: Portuguese author Jose Saramago was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998.

“It was really incredible how, in such a short space of time, his life had been transformed, at that moment, he felt as if he were floating in a kind of limbo, in a corridor joining heaven and hell, which made him wonder, with some amazement, where he had come from and where he would go next, because, judging by current ideas on the subject, it cannot be the same thing for a soul to be transported from hell to heaven as to be pushed out of heaven into hell.”

In wh at may be Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago’s most playful—and, perhaps, popular—novel, Tertuliano Maximo Afonso, a secondary school history teacher, views a film given to him by a colleague and discovers in the film an actor who looks exactly like him in every respect. Though the film was made five years before and the actor was wearing a mustache, the two men are identical otherwise. Tertuliano, a somewhat gloomy, divorced man, has always liked the routine of his solitary life, and though he is a daydreamer, he has never before acted on those dreams. When he sees his double, he is stunned. “One of us is a mistake,” he declares, and as he begins, typically, to overanalyze the situation and chat with himself about the fact that “never before in the history of humanity have two identical people existed in the same place and time,” he finds himself wondering what it would be like to find and meet this double.

at may be Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago’s most playful—and, perhaps, popular—novel, Tertuliano Maximo Afonso, a secondary school history teacher, views a film given to him by a colleague and discovers in the film an actor who looks exactly like him in every respect. Though the film was made five years before and the actor was wearing a mustache, the two men are identical otherwise. Tertuliano, a somewhat gloomy, divorced man, has always liked the routine of his solitary life, and though he is a daydreamer, he has never before acted on those dreams. When he sees his double, he is stunned. “One of us is a mistake,” he declares, and as he begins, typically, to overanalyze the situation and chat with himself about the fact that “never before in the history of humanity have two identical people existed in the same place and time,” he finds himself wondering what it would be like to find and meet this double.

Telling Tertuliano’s story is a narrator who injects himself into the story. Self-conscious about his writing, he digresses, acts patronizing toward Tertuliano Maximo Afonso, and often makes arch comments about him to the reader. He plays with the reader as he constructs Tertuliano’s story, commenting at one point that Tertuliano’s thoughts “bore so little relevance” to his discovery of his double that if he were to include them in the novel, “the story we had decided to tell would inevitably have to be replaced by another.” He does not want to do this, of course, because “all our hard work” in constructing the first forty pages of the book would then be null and void. The narrator decides to “remain therefore with this bird in the hand (Tertuliano), rather than suffer the disappointment of seeing two fly away. Besides, we haven’t got time for anything else.”

As this narrator plays with logic and language, creates conversations and debates between Tertuliano and Common Sense, reflects on the origins and destinies of words, jokes with the reader, and generally shows off, he becomes a foil for Tertuliano Maximo Afonso, whose own “emotions have never been strong or enduring.” When Tertuliano rents dozens of videos in an effort to identify the look-alike actor he saw in the film, he finds his life transformed, however—”as if he were floating in a kind of limbo, in a corridor joining heaven and hell, which made him wonder, with some amazement, where he had come from and where he would go to next.” He views himself “as a chrysalis in a state of profound withdrawal and undergoing a secret process of transformation.” Even the math teacher, who recommended the film to him, notices his change. Eventually, he learns that the actor’s real name is Antonio Claro, he obtains his address and soon contacts Claro by telephone, arranging to meet him at a remote place, where their identical appearances will not be noticed.

Through a series of profound, dramatic ironies which unfold as Tertuliano and Antonio Claro meet, Saramago raises questions about identity and destiny, presenting Tertuliano Maximo Afonso and Antonio Claro (Daniel Santa Clara) as they compare their lives, note their different approaches to life , and then find their natural curiosity becoming transformed into resentment. “There is one too many of us in the world,” Tertuliano declares. The climax is shocking—quite different from what the reader expects—and just when you think that the surprises have ended, a final surprise awaits.

, and then find their natural curiosity becoming transformed into resentment. “There is one too many of us in the world,” Tertuliano declares. The climax is shocking—quite different from what the reader expects—and just when you think that the surprises have ended, a final surprise awaits.

Readers new to Saramago should be forewarned that his style can be off-putting. The quotation which opens this review is representative of the entire book—page after page of run-on sentences, few paragraphs indentations, and a lack of quotation marks. The reader must read dialogue carefully, since there is no punctuation to set off which remarks are made by which character. Despite this flouting of convention, however, the novel reads quickly, and Saramago achieves a remarkably conversational tone within this complex style. The novel is often humorous, and the author clearly is enjoying himself as he plays with the subject of identity. Lively and clever, The Double gives us the game of life, played with a whole new set of rules.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://acariciando.blogspot.com

Seeing double: http://www.between-the-lines.co.uk