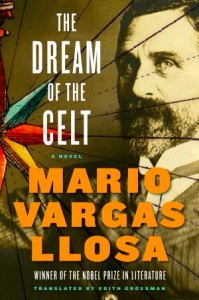

Note: Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010.

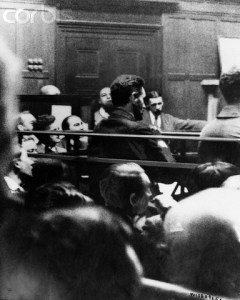

“My good man, how could you be so stupid?…How could you put such things on paper? And if you did, how could you not take the basic precaution of destroying those diaries before embarking on a conspiracy against the British Empire?…Portions of those diaries…are all over London. In Parliament, the House of Lords, Liberal and Conservative clubs, editorial offices, churches. It’s the only topic of conversation in the city.”– Mr. Gavan Duffy, solicitor for Roger Casement, as he appeals Casement’s death sentence.

In jail awaiting the results of his appeal of the death sentence for his attempt to help Irish rebels by bringing guns and ammunition into Ireland from Germany, Roger Casement, age fifty-one in 1916, is ill, friendless, and suffering emotionally. Casement has been jailed following his capture on Banna Strand, where he was expecting to be met by the rebels he planned to help with twenty thousand rifles, ten machine guns, and five million rounds of ammunition. He had secured these munitions in Germany, along with the promise of help, and had traveled to Ireland in a German submarine, trailed by a ship loaded with the armaments. The uprising was scheduled to occur on April 23, 1916, and Casement, who was opposed to the uprising without more involvement of the populace, had planned his own arrival with weapons to coincide with the April 23 date. Upon his scheduled arrival at Banna Strand, no one is there to meet him – the date was changed after he departed from Germany. The ship with all the guns and ammunition was sunk, and Casement was captured.

In jail awaiting the results of his appeal of the death sentence for his attempt to help Irish rebels by bringing guns and ammunition into Ireland from Germany, Roger Casement, age fifty-one in 1916, is ill, friendless, and suffering emotionally. Casement has been jailed following his capture on Banna Strand, where he was expecting to be met by the rebels he planned to help with twenty thousand rifles, ten machine guns, and five million rounds of ammunition. He had secured these munitions in Germany, along with the promise of help, and had traveled to Ireland in a German submarine, trailed by a ship loaded with the armaments. The uprising was scheduled to occur on April 23, 1916, and Casement, who was opposed to the uprising without more involvement of the populace, had planned his own arrival with weapons to coincide with the April 23 date. Upon his scheduled arrival at Banna Strand, no one is there to meet him – the date was changed after he departed from Germany. The ship with all the guns and ammunition was sunk, and Casement was captured.

Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa opens this fictionalized biography of Roger Casement with Casement’s wait for clemency, and as he reconstructs Casement’s life as a reformer and advocate for benighted native populations being exploited by various countries and corporations, he returns again and again to Casement as he rethinks every aspect of his life. Casement concludes, in most cases, that he acted honorably – or tried to.

From his first job with a company which shipped cargo and passengers between Great Britain and West Africa, Casement is fascinated by Africa, wanting to be an explorer like Dr. David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley. He gives up his job and makes his first trip to Africa at age twenty, working for four years with Stanley, and he believes that they are going to improve living conditions, rid the country of plagues, and educate and Christianize the local population. He quickly discovers that Stanley has had the tribal chiefs sign contracts to provide manual labor, lodgings, guides, and food, though they cannot read or write and have no idea what they have “signed.” As the years pass, he comes to the conclusion that Stanley, his former hero, is the “most unscrupulous villain the West had excreted onto the continent of Africa.” The author details horrific abuses committed against humanity in the name of “civilization” under the aegis of King Leopold II, but Stanley and others have known of these abuses, allowed them to continue, and have been a party to similar abuses by entrepreneurs from their own country.

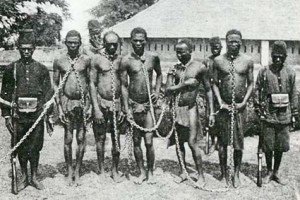

The devastating results on the local population have been almost incalculable. In 1884, for example, Lukolela had more than five thousand inhabitants. Twenty years later, its population is just three hundred fifty-two, most of them old or ill, with only eighty-two able to work. All the rest have died or been enslaved by “greedy, brutal, insatiable” soldiers or overseers. Eventually, back in England, Casement, who has become friends with Joseph Conrad during his time in the Congo, founds the Congo Reform Association (with Edmund D. Morel) and comes to know William Butler Yeats, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw, G. K. Chesterton, and John Galsworthy, who support it. In 1903, he becomes a British consul and returns to the Congo “to verify the truth regarding the accusations of abuses against the indigenous population in the rubber zones.” His report to the government overwhelms those who read it.

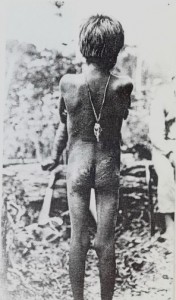

In 1910, he accepts another assignment – to travel to the Peruvian Amazon to Iquitos and Putumayo, investigating the Peruvian Amazon Company, owned by Julio C. Arana, who has many British investors in London. The abuses there are at least as bad as they have been in the Congo, with Senor Arana controlling enormous amounts of land over which he has total control. “The system of exploitation was so extreme, it destroyed spirits even before bodies. The violence that victimized them annihilated the will to resist, the instinct to survive, and transformed the indigenous people into automatons paralyzed by confusion and terror.” Again, Casement reports publicly on the abuses, and, because the abuses are so horrific that the many British investors cannot believe them, he actually has to return to Peru for even more documentation (with a camera) before people can absorb the horrors.

While investigating all these horrors, he also becomes convinced that the British rule in Ireland, though less bloody, is as much of a crime against the Irish population as the exploitation of indigenous people has been in the Congo and Amazonia. Eventually, he spends eighteen months in Germany negotiating for arms and aid, believing that if the Germans will use their enmity against the British to help the Irish, the chances of a successful Irish rebellion will be increased. Casement’s role in the rebellion might not have been a death penalty issue if Casement had not also written diaries in which he describes his sexual behavior, regarded as deviant, in detail. Whether or not these events are real, part fantasy (as the author believes), or pure fantasy are unknown – the original diaries are only now becoming public.

Vargas Llosa’s clear and unambiguous descriptions, including those of atrocities and torture, ensure that the reader will not ignore the totality of the horror or the unusual settings, and the author’s impression of Casement is clearly one of admiration for his humanitarian impulses. The biggest

difficulty with this book is that it feels like three not-quite-complete books, instead of one unified book about one man, fully revealed. The sexual issues mentioned throughout the diaries, which may affect Casement’s reputation to the present day, are issues which the author clearly wants to keep separate from Casement’s efforts on behalf of indigenous peoples in the Congo and Peru. In an interview he indicates he thinks Casement’s private diaries are part fantasy, but unless more information is discovered, no one can ever be sure. In the meantime, Casement’s contribution to history regarding human rights abuses is undeniable, and his courage in reporting them is unquestionable.

ALSO by Mario Vargas Llosa: THE BAD GIRL, THE FEAST OF THE GOAT, DEATH IN THE ANDES, THE DISCREET HERO

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.shelf-awareness.com

The portrait of Casement, by Sara Purser, may be found in the National Gallery in Dublin: http://peri-dublin.blogspot.com

The slaves on a Congo rubber plantation are seen on http://lupusuva1phototherapy.com/

A child, whipped with a chicotte, a fearsome hippopotamus hide whip, shows the scars: http://www.survivalinternational.org

Roger Casement in the courtroom during his trial: http://pcolman.wordpress.com