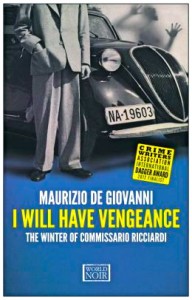

Note: This novel, originally published in 2013, has been re-released in July, 2018, in the wake of the enormous popularity of the series which resulted. This review from 2013 is for the first novel featuring Commissario Ricciardi and was written at that time of its release. Since then, eight more Ricciardi novels have been published, all of which are reviewed on this site, with links provided at the end of this review. A ninth novel is expected in August, 2018. Four additional novels featuring Inspector Lojacono in contemporary Naples have also been published and reviewed here. –Mary Whipple, July, 2018.

“[Ricciardi] saw the dead. Not all of them, and not for long: only those who had died violently, and only for a period of time that revealed extreme emotion, the sudden energy of their final thoughts…as if to conclude something the soul had begun before being torn away. It came upon him like the ghost of a galloping horse, leaving him no time to avoid it…Yet another scar on his soul.”

Those who have been fans of Stieg Larsson’s Mikael Blomqvist and Jo Nesbo’s Harry Hole will find Maurizio De Giovanni’s Baron Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi, the Neapolitan police hero of the first of a projected tetralogy of mysteries, a completely different kind of character. Commissario Ricciardi is neither as hard-boiled as Blomqvist nor as damaged by alcohol and its side effects as Hole. In this novel, which is far more operatic in its structure than the Nordic novels, Maurizio De Giovanni creates a main character who feels far more sympathetic than those other two heroes. Now thirty and orphaned, Ricciari has no woman and no family life, though he enjoys the undying support of his tata, Rosa Vaglio, a seventy-year-old woman who has been a family employee since she was fourteen. He works at least twelve hours a day investigating the most challenging murders in Naples, and he is obviously still suffering from a trauma which occurred when he was a child and led to the first of his “Incidents.”

Those who have been fans of Stieg Larsson’s Mikael Blomqvist and Jo Nesbo’s Harry Hole will find Maurizio De Giovanni’s Baron Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi, the Neapolitan police hero of the first of a projected tetralogy of mysteries, a completely different kind of character. Commissario Ricciardi is neither as hard-boiled as Blomqvist nor as damaged by alcohol and its side effects as Hole. In this novel, which is far more operatic in its structure than the Nordic novels, Maurizio De Giovanni creates a main character who feels far more sympathetic than those other two heroes. Now thirty and orphaned, Ricciari has no woman and no family life, though he enjoys the undying support of his tata, Rosa Vaglio, a seventy-year-old woman who has been a family employee since she was fourteen. He works at least twelve hours a day investigating the most challenging murders in Naples, and he is obviously still suffering from a trauma which occurred when he was a child and led to the first of his “Incidents.”

A man of deep feelings, Ricciardi is supernaturally sensitive, attuned to the inner natures of those who die violently. He actually sees these victims in their last moments and suffers intensely from the occult experiences he “shares” with them, overhearing their final words or thoughts at the time of their deaths. He often sees ghosts, sometimes the ghosts of those he could not help, and each time they repeat the same last words – among them a man killed by a pickpocket to whom the victim would not give up his possessions, and a farmworker, sitting under a vine, stabbed to death, who insists “By God I didn’t touch your wife.” These incidents “had taught him that hunger and love are the source of all atrocities, whatever forms they may take: pride, power, envy, jealousy. In all cases, hunger and love. They were present in every crime.” Especially hunger, both real and emotional.

The turmoil of Via Toledo, Naples

Set in Naples in 1931, the novel takes place during the early rule of Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, at a time in which the gap between the wealthy and poor is enormous. Angelo Garzo, the Vice Questore in charge of Ricciardi’s department, “whose life was dedicated to providing absolute satisfaction to those in power,” warns the department, however, that “There are no suicides, no homicides, no robberies or assaults, unless it is inevitable or essential…A fascist city is clean and wholesome, there are no eyesores.” Ricciardi himself notes, however, that Via Toledo clearly divides Naples into two areas, the wealthy areas at the bottom of the hill, and those of the working class and poor near the top: “the city of feasting and that of despair, the sated city and the hungry one.”

The Royal Theatre of San Carlo, Naples

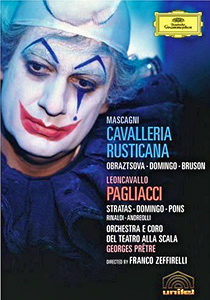

When Ricciardi and his only friend, Brigadier Raffaele Maione, age fifty, are called to the Royal Theatre of San Carlo to investigate the murder of the world’s greatest tenor, Ricciardi notes that each time the elegant theatre opens at night, the cafes are “teeming with life and pleasure…music and laughter,” but that upon his arrival, “children in tatters stood on tiptoe [in the winter cold], their bare feet suffering from chilblains, to catch a glimpse of something.” For them, police investigations are the equivalent of the operas the aristocracy so enjoys. In this case, Arnaldo Vezzi, the tenor scheduled to sing the role of Canio, the clown, in Pagliacci, the second opera on a double bill with Cavalleria Rusticana, has been murdered with a shard of mirror in his dressing room. When Ricciardi enters to find the body, it softly sings an aria, which, translated, reads: “I will have vengeance, My rage shall know no bounds, And all my love. Shall end in hate.” Vengeance, rage, love, and hate – all emotions Ricciardi believes are behind all murders. Ironically, this aria is from Cavalleria Rusticana, the first opera on the bill, not Pagliacci, which Vezzi himself was scheduled to sing.

Poster for the 1982 film of Pagliacci, starring tenor Placido Domingo

Ricciardi hates opera, being “contemptuous of those colorful costumes, those modulated voices, those archaic, cultured words in the mouths of poor devils who were actually starving to death,” and he “didn’t like the theatrical representation of emotions…[which] never came in just one flavor…there were a thousand facets to [them].” Accordingly, he becomes friendly with a priest, Don Pierino Fava, whose passion for opera is fulfilled each month when, with help from the staff, he hides in a niche backstage so he can see the opera privately (and free). The priest was present when Vezzi was killed and may have seen the victim immediately before his death. Polar opposites in their views of life, the priest and Ricciardi converse about opera and about this crime, sharing their philosophical beliefs and enjoying some good-natured arguments. At one point, however, Ricciardi horrifies the priest, bursting out that “For you damnation is only a word. Believe me when I tell you that damnation is the relentless perception of sorrow…other people’s sorrow that becomes your own, that stings like a whip… that infects your blood.”

Consummately romantic at heart, with exaggerated but likable characters and heart-breaking situations more akin to opera than to real life, Maurizio De Giovanni’s surprising mystery is both dramatic and compassionate, filled with a kind of resonance rare among dark mysteries. Lovers of opera, and I am one, will be intrigued with all the references to love, vengeance, murder, sorrow, pride, envy, and jealousy which seem to motivate most operas, and, Ricciardi would have us believe, most murders. As is also the case with opera, the characters are sometimes stereotyped, their actions pre-ordained by the traditions of operatic plot. Having established Ricciardi’s occult talents in the opening pages, the reader understands that a significant amount of “willing suspension of disbelief” is necessary here, and as Ricciardi’s own life, like those of the other main characters, is also its own romantic opera, there is no pretense of realism. I will be interested to see how the romanticism holds up in Blood Curse: The Springtime of Commissario Ricciardi, the second in the series, scheduled for release on May 7, 2013 (Europa). I thoroughly enjoyed the over-the-top style of this one.

Consummately romantic at heart, with exaggerated but likable characters and heart-breaking situations more akin to opera than to real life, Maurizio De Giovanni’s surprising mystery is both dramatic and compassionate, filled with a kind of resonance rare among dark mysteries. Lovers of opera, and I am one, will be intrigued with all the references to love, vengeance, murder, sorrow, pride, envy, and jealousy which seem to motivate most operas, and, Ricciardi would have us believe, most murders. As is also the case with opera, the characters are sometimes stereotyped, their actions pre-ordained by the traditions of operatic plot. Having established Ricciardi’s occult talents in the opening pages, the reader understands that a significant amount of “willing suspension of disbelief” is necessary here, and as Ricciardi’s own life, like those of the other main characters, is also its own romantic opera, there is no pretense of realism. I will be interested to see how the romanticism holds up in Blood Curse: The Springtime of Commissario Ricciardi, the second in the series, scheduled for release on May 7, 2013 (Europa). I thoroughly enjoyed the over-the-top style of this one.

Note: This novel was a FINALIST for the Crime Writers Association International Dagger Award in 2012.

ALSO by de Giovanni (Inspector Ricciardi series): BLOOD CURSE: The Springtime of Commissario Ricciardi (#2), EVERYONE IN THEIR PLACE (#3), THE DAY OF THE DEAD (#4) BY MY HAND (#5) VIPER (#6), THE BOTTOM OF YOUR HEART (#7), GLASS SOULS: MOTHS FOR COMMISSARIO RICCIARDI (8) NAMELESS SERENADE (#9)

Inspector Lojacono series: THE CROCODILE (#1) , THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#2), DARKNESS FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#3), COLD FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#4), PUPPIES (#5)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.massimo.delmese.net

Via Toledo may be seen here: http://goldringtravel.blogspot.com

The beautiful San Carlo Opera is found on http://www.neac2.eu

The poster from the Franco Zeffirelli film of Pagliacci (1982) appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/

The Questura, in 2012: http://www.vesuvius.it