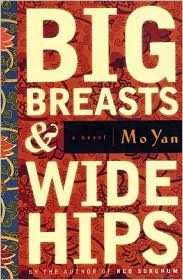

Note: Mo Yan has been named WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature for 2012.

“It didn’t take Mother long to realize the cruel reality that for a woman, not getting married was not an option, not having children was not acceptable, and having only daughters was nothing to be proud of. The only road to status in a family was to produce sons.”

Setting this monumental family saga in Gaomi, in northeast China, where he grew up, Mo Yan, a member of the People’s Liberation Army who studied writing at their art academy, presents a realistic, rather than glorified, picture of life in China. Vividly portraying political and historical events—most of them bloody—over the course of the twentieth century, he portrays family life in rural China from the Boxer Rebellion to the Communist Revolution, the Japanese invasion, the Cultural Revolution, and the death of Mao. Jintong, the only son of Shangguan Lu, tells the story of his mother, his sisters, and their families as they live through these seminal events.

Setting this monumental family saga in Gaomi, in northeast China, where he grew up, Mo Yan, a member of the People’s Liberation Army who studied writing at their art academy, presents a realistic, rather than glorified, picture of life in China. Vividly portraying political and historical events—most of them bloody—over the course of the twentieth century, he portrays family life in rural China from the Boxer Rebellion to the Communist Revolution, the Japanese invasion, the Cultural Revolution, and the death of Mao. Jintong, the only son of Shangguan Lu, tells the story of his mother, his sisters, and their families as they live through these seminal events.

Shangguan Lu’s early marriage and domestic life unfolds through flashbacks. With an infertile husband whose family beats and abuses her for failing to produce a son, she resorts to extreme measures, becoming pregnant by several different men and giving birth to eight daughters before finally producing a male heir. Showing direct, ironic parallels between the life of Shangguan Lu and the life of her farm animals, Mo Yan describes nature without lyricism or sentimentality. Nature and life, as we see them here, are cruel and uncertain.

Through the developing stories of the eight daughters, their marriages, and their careers, the history of China from 1939 to the 1990s unfolds. Laidi, Eldest Sister, marries the leader of the Black Donkey Musket Band, which fights the Japanese during World War II, but Laidi’s husband later becomes a turncoat, joining the Japanese and fighting against the husband of another sister, who commands the anti-Japanese forces. The story of the Nationalists during the War of Resistance (1937 – 1945) is matched with the story of another sister, who is a fervent member of the People’s Liberation Army, fighting them.

No political movement in China escapes blame for the unconscionable atrocities, graphically described, which are inflicted both on their enemies and on the local population. Facing imminent starvation and death from exposure, rural workers are forced to make long marches, deprived of their land, and punished for being human. Every political movement regards them as mere ciphers, without individuality, to be moved around or eliminated, as necessary, in the drive for power.

Though political movements do not respect individuals, the author obviously admires the resilient spirit of women such as Shangguan Lu and her daughters, forced to run the farms and feed their families, virtually without resources, since their husbands are either dead or off fighting for causes. Often desperate, parents, such as Shangguan Lu, are sometimes forced to sell children, either for adoption or prostitution, in order that the others may survive.

do not respect individuals, the author obviously admires the resilient spirit of women such as Shangguan Lu and her daughters, forced to run the farms and feed their families, virtually without resources, since their husbands are either dead or off fighting for causes. Often desperate, parents, such as Shangguan Lu, are sometimes forced to sell children, either for adoption or prostitution, in order that the others may survive.

Mo Yan’s novel is big, and it is important, the first really thorough portrait of rural life in China during the major historical movements of the twentieth century. His style, while often exciting is also brutally realistic and graphic in its violence. Though the author includes legends and cultural traditions as part of his picture of family life, the Shangguan family comes alive primarily through minute details. Physical detail, such as the kind of clothing which nursing mothers wear so that they can feed their children in very cold weather, descriptions of the silent “snow market,” pictures of school life, and even facts and figures about the minimum amount of grain needed per person to keep farm workers alive for the harvest season help bring this culture and these people to life. But the author also uses satire, wry comments, and black humor, to criticize totalitarian governments and closed societies.

Providing a helpful cast of characters at the beginning of this episodic novel, Mo Yan shows us a society in which individualism has little meaning. The narrator and only son, Jintong, is neither a hero nor a fully realized character in the western sense, and though much detail is given about what characters do and how they behave, less consideration is given to how they think and why they behave as they do.

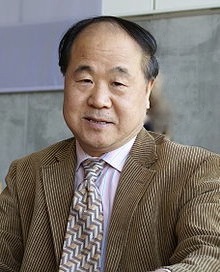

Author of nine novels, Mo Yan, whose pen name, ironically, means “Don’t Speak,” has sometimes been mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature. The vibrancy and accuracy of his portraits of Chinese life, his steadfast insistence on showing life as it is, rather than life as it ought to be, and his willingness to take risks for his art make him one of the most influential writers in the People’s Republic, despite the fact that many of his books are banned there.

ALSO by Mo Yan: SHIFU, YOU’LL DO ANYTHING FOR A LAUGH and FROG

Notes: The author’s photo appears on his Wiki page. http://en.wikipedia.org

The photo of Gaomi is from http://www.tripadvisor.com

The picture of the women in the People’s Liberation Army comes from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn