If I still say ‘we’ when I talk about that day [of my mother’s burial], it’s out of habit, for the years welded us together like two parts of a sword we could use to defend each other. Writing out the inscription for her headstone, I understood that death takes place in language first, in that act of wrenching subjects from the present and planting them in the past. Completed actions. Things had a beginning and an end, in a time that’s gone forever.” – Adelaida Falcon

Though there are, at present, over a thousand reviews on this website, this is the first, of all the international fiction I have read and reviewed over the past ten years, that is written by a Venezuelan author about everyday life in this country where turmoil and bloodshed often dominate daily life. Author Karina Sainz Borgo, born and raised in Caracas, worked as a journalist there before emigrating to Spain a few years ago. Her experience in Caracas holds her in good stead here as she gets the novel off to a quick, almost journalistic, start, setting the scene and developing her main character, Adelaida Falcon, an editor in Caracas. Adelaida’s mother, a teacher who has just died, was the first of her family to graduate from college, and she went on to encourage her daughter to pursue her own writing. Her father, referred to as the Dead One, has never been part of her life. Sainz Borgo continues by establishing the fraught life Adelaida and her neighbors are forced to endure, with shortages of everything needed for a healthy life, including food and medicine. “We could only watch as everything we needed vanished: people, places, friends, recollections, food, serenity, peace, sanity. ‘Lose’ became a leveling verb, and the Sons of the Revolution wielded it against us,” Adelaida comments. The student brother of her next door neighbor, has been arrested, along with others, by these same Sons of Revolution, and he has spent more than a month inside a prison, – “beaten, bludgeoned in a corner, or raped with the barrel of a gun.” Now they do not know if he is alive or dead.

Though there are, at present, over a thousand reviews on this website, this is the first, of all the international fiction I have read and reviewed over the past ten years, that is written by a Venezuelan author about everyday life in this country where turmoil and bloodshed often dominate daily life. Author Karina Sainz Borgo, born and raised in Caracas, worked as a journalist there before emigrating to Spain a few years ago. Her experience in Caracas holds her in good stead here as she gets the novel off to a quick, almost journalistic, start, setting the scene and developing her main character, Adelaida Falcon, an editor in Caracas. Adelaida’s mother, a teacher who has just died, was the first of her family to graduate from college, and she went on to encourage her daughter to pursue her own writing. Her father, referred to as the Dead One, has never been part of her life. Sainz Borgo continues by establishing the fraught life Adelaida and her neighbors are forced to endure, with shortages of everything needed for a healthy life, including food and medicine. “We could only watch as everything we needed vanished: people, places, friends, recollections, food, serenity, peace, sanity. ‘Lose’ became a leveling verb, and the Sons of the Revolution wielded it against us,” Adelaida comments. The student brother of her next door neighbor, has been arrested, along with others, by these same Sons of Revolution, and he has spent more than a month inside a prison, – “beaten, bludgeoned in a corner, or raped with the barrel of a gun.” Now they do not know if he is alive or dead.

Despite additional horrors which are hinted at, Adelaida maintains a remarkably conversational tone throughout her story. She refuses to waste time whining and develops a kind of intimacy of style which draws in the reader. As she describes her mother’s burial and the financial difficulties involved, she also worries that someone may dig up her mother’s body in order to take her glasses and the other personal items buried with her. A group of twenty to thirty thugs is having a bizarre funeral nearby, and as she and the driver escape, she concludes that “I died once more. I was never able to rise again from all the deaths that accumulated in my life story that afternoon. That day I became my only family.” Returning home, as she packs up her mother’s possessions, she muses about some old Cartuja plates from Seville, which had been left to her grandmother, and which she and her mother had used in their everyday life, and she thinks about her mother’s older relatives who live along the north coast, about a hundred miles west of Caracas. Again, she is reminded that she and her mother have lived alone in the city for nearly their whole lives. Unlike other families, “we came from nobody and belonged to nothing.”

Despite additional horrors which are hinted at, Adelaida maintains a remarkably conversational tone throughout her story. She refuses to waste time whining and develops a kind of intimacy of style which draws in the reader. As she describes her mother’s burial and the financial difficulties involved, she also worries that someone may dig up her mother’s body in order to take her glasses and the other personal items buried with her. A group of twenty to thirty thugs is having a bizarre funeral nearby, and as she and the driver escape, she concludes that “I died once more. I was never able to rise again from all the deaths that accumulated in my life story that afternoon. That day I became my only family.” Returning home, as she packs up her mother’s possessions, she muses about some old Cartuja plates from Seville, which had been left to her grandmother, and which she and her mother had used in their everyday life, and she thinks about her mother’s older relatives who live along the north coast, about a hundred miles west of Caracas. Again, she is reminded that she and her mother have lived alone in the city for nearly their whole lives. Unlike other families, “we came from nobody and belonged to nothing.”

The real action begins when Adelaida hears what sounds like a robbery upstairs, then sees five men in military intelligence uniforms exiting her building carrying long guns, a microwave oven, and a computer – while also dragging suitcases. Soon she realizes that she has not seen Aurora Peralta, her neighbor, in weeks. She has been so busy with her mother’s palliative care and trying to save money and store food for the future that she has not realized how much time has passed since she last saw Aurora. When she goes out for food, and stands in the bread line – and fails to get it – she returns home to find the locks changed to her own apartment. Then she discovers that her home is occupied by a group of five women in the civil militia. When she accosts them, wanting, at least, to reclaim her books, they assert themselves, tearing apart a book, spitting at her, breaking her mother’s Cartuja plates, and pistol-whipping her. She has now lost her apartment, has nowhere to go, and is hurting.

All this detail is part of the author’s clever lead-in to the events upon which the rest of the novel turns. Though she includes flashbacks which allow the reader to fill in some blanks, Sainz Borgo selectively withholds information, as Adelaida would have done, allowing the past to unfold slowly and add to the suspense. A few new characters appear, as does a love story, and Adelaida is forced to take the kind of action that no human being should ever be forced to take, even in defense of life. Her only chance at survival is to find a place in her apartment building where she can stay, at least temporarily, without being seen by the militia. Eventually, she decides she must leave Caracas, but she has no way of knowing how she will do that. Flashbacks to her life with her mother include another shift of focus and memory in which she and her mother go to the National Gallery. There they see a painting called “Young Mother” by Arturo Michelena, from 1889, which makes her aware of the “strange tidal pull of beauty that mothers emit, beings of faint perfume, women who hide beneath the morning sun,” a scene indicating she has become totally aware of herself as a female. In direct contrast, the next scene from the present is one which no one who reads it is likely to forget, and which, because of the degree to which a reader will have identified with Adelaida, will make her situation in Caracas more desperate than anything seen in the novel so far.

The last half of the novel concentrates on Adelaida’s plan of escape from Caracas and its difficulty. Other aspects of her life, not even hinted at previously, suddenly give some new insights into her past through flashbacks – and into the horrors of her present. Her discovery of a cache of papers, some of which belonged to a chef, helps her to get organized, even as other aspects of her life and the lives of those around her become more fraught with danger. Because Adelaida has come to feel so “normal” and sympathetic to the reader, her difficulties take on added impact as she tries to escape, especially when she must behave in unfamiliar ways under new circumstances. As the final scenes play out, a reader would have to have a heart of stone not to wish her well, despite the sometimes excessive emotionalism and occasional sentimental interludes in which she remembers the past. Author Karina Sainz Borgo has done what no other writer has managed to do in the past ten years – she has told an exciting and involving story of Venezuela to a whole new audience and helped readers to understand some of what is happening in a country which has been shrouded in secrecy for many years.

Romulo Betancourt (1908-1981) was considered the “father of Venezuelan democracy.” He was president from 1945-1948 and from 1959-1964, well before the time of this novel.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.harpercollins.com/

The cartuja plate from Seville, Spain, is found on https://www.ebay.com

Arturo Michelena’s “Young Mother” leads Adelaida into a new understanding of women and child-bearing. https://eclecticlight.co/

Paella, one of the most famous dishes of Spain, would have been prepared often by the chef whose files are discovered by Adelaida. https://spainwineguide.com/

Romulo Betancourt (1908-1981) was considered the “father of Venezuela democracy.” He was president from 1945-1948 and from 1959-1964, before the time of this novel.

Author Deborah Levy’s unique and hypnotic character study opens with Saul Adler, a twenty-eight-year-old British historian writing a lecture on “the psychology of male tyrants,” in which he describes the way Stalin flirted with women by flicking bread at them across the dinner table.

Author Deborah Levy’s unique and hypnotic character study opens with Saul Adler, a twenty-eight-year-old British historian writing a lecture on “the psychology of male tyrants,” in which he describes the way Stalin flirted with women by flicking bread at them across the dinner table.

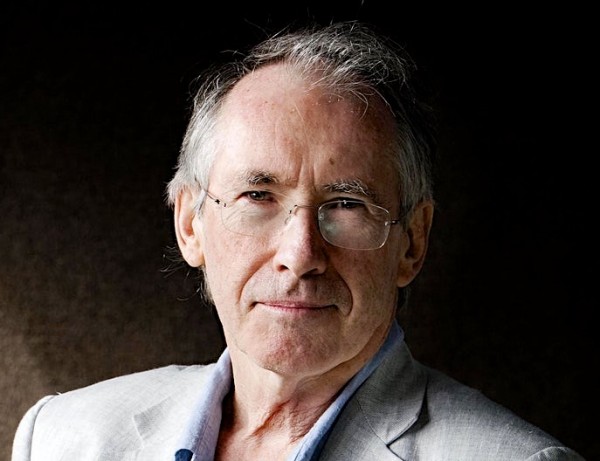

Before one reads even the first sentence of Chapter One, author Ian McEwan uses the introductory epigraph to clearly establish the satirical nature of this work. Inspired by Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, an existential novel in which the main character, Gregor Samsa, finds himself gradually transformed from a human being into a cockroach, McEwan gives that concept a twist. Here main character Jim Sams has experienced the reverse, starting out as a cockroach and becoming human. This change has come suddenly. After waking up in bed one morning, he sees that he now has fewer legs and, most “revolting,” he now feels a “slab of slippery meat…squat and wet in his mouth…[which] moved of its own accord to explore the vast cavern of his mouth.” His color has changed, as has his vision, and his “vulnerable” flesh now lies outside his skeleton. Just last night this new human had made a difficult trip in his previous body from the Palace of Westminster through the underground garage, the gutters, and across Parliament Square. A political demonstration had been going on, complete with horse guards and police, but somehow he had avoided them, making his way from there to the bedroom of a residence for the rest of the night. Now, however, he remembers he is on an important, solitary mission. When the phone beside the bed rings, he is barely able to move in his new body, and he misses the call, only to be greeted by a young woman at his door who says, “Prime Minister, it’s almost seven thirty.” There is a Cabinet meeting scheduled for nine o’clock.

Before one reads even the first sentence of Chapter One, author Ian McEwan uses the introductory epigraph to clearly establish the satirical nature of this work. Inspired by Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, an existential novel in which the main character, Gregor Samsa, finds himself gradually transformed from a human being into a cockroach, McEwan gives that concept a twist. Here main character Jim Sams has experienced the reverse, starting out as a cockroach and becoming human. This change has come suddenly. After waking up in bed one morning, he sees that he now has fewer legs and, most “revolting,” he now feels a “slab of slippery meat…squat and wet in his mouth…[which] moved of its own accord to explore the vast cavern of his mouth.” His color has changed, as has his vision, and his “vulnerable” flesh now lies outside his skeleton. Just last night this new human had made a difficult trip in his previous body from the Palace of Westminster through the underground garage, the gutters, and across Parliament Square. A political demonstration had been going on, complete with horse guards and police, but somehow he had avoided them, making his way from there to the bedroom of a residence for the rest of the night. Now, however, he remembers he is on an important, solitary mission. When the phone beside the bed rings, he is barely able to move in his new body, and he misses the call, only to be greeted by a young woman at his door who says, “Prime Minister, it’s almost seven thirty.” There is a Cabinet meeting scheduled for nine o’clock.

A novel written by James Sallis is always a cause for celebration, if you enjoy high-powered surprises and compressed and insightful writing representing several different genres of crime narrative.

A novel written by James Sallis is always a cause for celebration, if you enjoy high-powered surprises and compressed and insightful writing representing several different genres of crime narrative.

Three strikingly similar murders have taken place in Glasgow during 1969, and police have made no progress apprehending the killer, nicknamed The Quaker.

Three strikingly similar murders have taken place in Glasgow during 1969, and police have made no progress apprehending the killer, nicknamed The Quaker.