“Deep in Honduras in a region called La Mosquitia, lie some of the last unexplored places on earth. Mosquitia is a vast, lawless area…of rainforests, swamps, lagoons, mountains…and the thickest jungle in the world….For centuries, [it] has been home to one of the world’s most persistent and tantalizing legends. Somewhere in this impassable wilderness, it is said, lies a “lost city” built of white stone. It is called Ciudad Blanca, the “White City,” also referred to as the “Lost City of the Monkey God.”

No one knows whether the “Lost City” actually exists and, if it does, whether it was built by the Mayas or some other, unknown indigenous group, but Mosquitia’s thirty-two thousand square miles, filled with rainforests, swamps, lagoons, rivers, mountains, ravines, waterfalls and roaring torrents have been virtually impassable throughout modern history, and early maps have labeled this place “Portal del Infierno,” or “Gates of Hell.” Any adventurer willing to test himself against these natural barriers would also have to be willing to deal with deadly snakes, jaguars, catclaw vines, with their hooked thorns, and hordes of insects and flies carrying unknown, possibly virulent diseases. And if someone were still determined to look for this lost city, s/he would also have to deal with equally dangerous human problems: Much of the area surrounding Mosquitia is ruled by drug cartels.

In February, 2015, an expedition of researchers decides to investigate this area, fearing that the on-going clear-cutting of the land could lead to the inadvertent discovery and destruction of ancient ruins and artifacts from the “lost cities” in Mosquitia. Author Douglas Preston joins a small group of researchers headed into a part of the jungle which “had not seen human beings in living memory.” Scientists, archaeologists, photographers, film producers, a British veteran skilled in jungle warfare and survival, and an expert in “lidar,” a form of radar involving Light Detection and Ranging, have been granted ten days to set up camp, do their research, and then leave the area, empty-handed. The President of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernandez, has provided army rangers, many of them members of indigenous Indian groups, for the protection of the researchers, and everyone involved in the project is to operate under the greatest of secrecy, revealing nothing about the location, keeping all notes, maps, and photographs under guard, and protecting the isolation of this area from those who might want to profit from the illegal sale of its artifacts.

Douglas Preston, well known co-author with Lincoln Child of a thriller series, has also worked as a writer and editor for the American Museum of Natural History, doing additional writing for National Geographic, Natural History magazine, Smithsonian, and the New Yorker, and this trip would be part of a story for National Geographic, its photographs supplied by David Yoder, also on the trip. Preston’s unique talents here – both his fiction writing experience and his scientific work – would allow him to recreate the historical background of the trip and the real events during the trip in ways at least as exciting as the fictional events of his thrillers. While other members of the research group would be taking notes and writing about their scientific and historical discoveries and their technical research, Preston would be able to provide a more general, less esoteric, presentation to the general public through his National Geographic story and through this book.

A fer-de-lance, one of the most poisonous snakes in the world, appears at camp the first night Preston is there. This one is being “milked” of its venom. Note the length of its fangs.

On his first night, after hacking his way into the jungle to make a place for his hammock, Preston discovers the howler monkeys, and later has an encounter with a fer-de-lance, one of the deadliest snakes in the world. “In a strange way the encounter sharpened the experience of being here,” he says. “It amazed me that a valley so primeval and unspoiled could still exist in the twenty-first century. It was truly a lost world, a place that did not want us and where we did not belong.” The next day the group slashes its way to the top of a hill and plaza, where they find geometric mounds and terraces and a large stone, probably an altar stone, hidden among the heavy vegetation, then more and more mounds and plazas. One scientist concludes that “all this terrain, everything you see here, has been entirely modified by human hands.” The lidar survey had been proved correct.

The were-jaguar effigy was found poking up from the ground on the first day of exploration of the site.

After a delay for torrential rains, they later return to the base of the pyramid they have been investigating, and discover some “weird stones.” Dozens of carved stone sculptures are poking out of the ground. The first thing Preston sees is “the snarling head of a jaguar sticking out of the forest floor, then the rim of a vessel decorated with a vulture’s head and more stone jars carved with snakes.” These were “lying here undisturbed since they had been left centuries ago – until we stumbled upon them…proof, if we needed it, that this valley had not been explored in modern times.” To protect the site containing the “were-jaguar” and the vessel, the archaeologist tapes it off, allowing only the three archaeologists from among the ten people in the group to go inside the lines, that “jewel of a place, as pure as you could find, untouched for centuries.” Much more lay below the surface, but it would take excavation a year later to see how much more.

Harrison Ford, active in Conservation International for fifteen years, is currently Vice Chairman of the group which financed the second trip to the “Lost City” in 2015. Here he consoles a baby orangutan at a sanctuary in Borneo.

Eventually coming out of the expedition with only their photos, and leaving every artifact behind, marked with tape, the group returns, and Preston writes a brief announcement about the discovery of a lost city in the Honduran rain forest, a story that goes viral and becomes front-page news. Academic controversy immediately results, some academics claiming that the expedition has made false claims and exaggerated the importance of the finds. The academic jealousies do not abate. In the meantime, most of the participants in the expedition have had to be hospitalized, and treated, some for many months, for leishmaniasis, an often fatal parasitic disease with “a long and terrible history,” almost unheard of in modern times. Soldiers guarding the site have also been diagnosed with this disease, which has no known cure, raising questions about pandemics and the possible reasons for the total abandonment of the “lost city,” seemingly overnight. A second trip in 2015, in which Preston also participated, has led to further discoveries, this expedition having been financed by Conservation International, of which actor Harrison Ford is currently the Vice Chairman. The first artifacts removed from the site in 2015, the “were-jaguar” metate and the vulture jar, have been presented to the President of Honduras, and the country is now gearing up to protect and promote its own heritage. The rest of the story will continue, and I suspect that National Geographic will keep us all up to date.

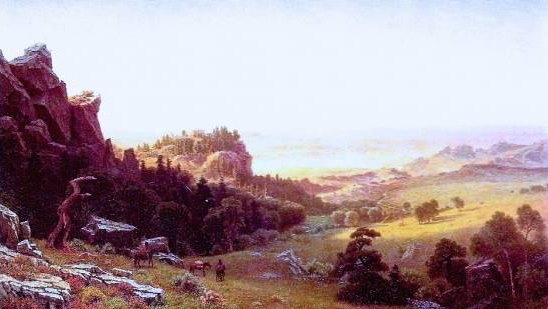

Somewhere in Honduras is a river like this, and somewhere along this river is the site of the Lost City. Photo by Dave Yoder, photographer for the expedition.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.nctv17.com/

The howler monkeys, which kept the author up all night on the night he arrived to make his camp for the expedition, are shown here: https://www.newscientist.com/

The dangerous fer-de-lance almost bites the author on the first night he is in camp in the jungle. Note the length of its fangs. http://www.capefearserpentarium.com/photos-23.html

The were-jaguar, found at the site of the Lost City, was partially buried among other effigies which were discovered at the Lost City. A year later, it was presented to the President Hernandez of Honduras. https://rperon1017blog.wordpress.com

Harrison Ford, shown here with a baby orangutan at a sanctuary in Borneo, has been involved with Conservation International for fifteen years and is now Vice Chairman of the organization. This organization financed the second expedition to the site in later 2015. http://yearsoflivingdangerously.com/

The photo of the winding river in Honduras, which may or may not be the river near which the Lost City was found, is by Dave Yoder, the photographer for the expedition. http://www.mirror.co.uk

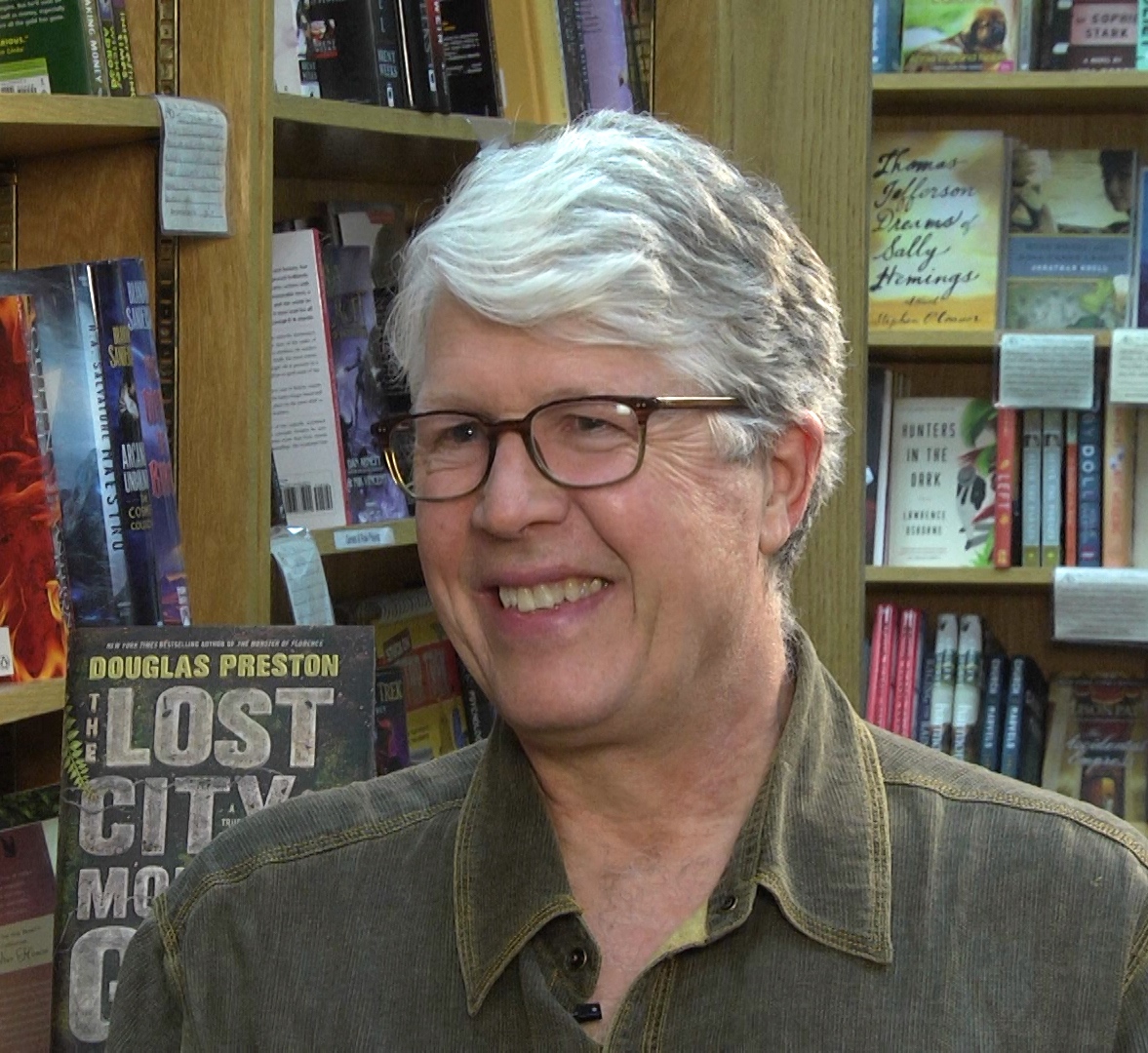

In 1874, the island of Tasmania, one hundred fifty miles off the southeast coast of Australia, is boiling with rage. Once a penal colony filled with the hardest criminals, and the site of almost total genocide of the original aboriginal inhabitants by the British, Tasmania, in 1874, is a seething cauldron of hungry men and the toughest of women, many of them homeless, trying to survive the only way they know – by using whatever weapons they have at hand to gain what they need to stay alive. Adding to the problems of the poor, the Launceston and Western Railway Company, run by the colonizers, has recently accumulated large debts at the hands of speculators, and the Tasmanian government has just decided to make its citizens pay for those losses. Learning that the legislature has “voted to confiscate our property, steal our money, and make ruins of our lives,” large crowds gather to take matters into their own hands. “It is because they believe us weak,” they decide. “Because they believe the undue exercise of power over the supine and the insipid is their prerogative.” Resentment against the police is high, and the tempers of the poor and hungry are shorter than short.

In 1874, the island of Tasmania, one hundred fifty miles off the southeast coast of Australia, is boiling with rage. Once a penal colony filled with the hardest criminals, and the site of almost total genocide of the original aboriginal inhabitants by the British, Tasmania, in 1874, is a seething cauldron of hungry men and the toughest of women, many of them homeless, trying to survive the only way they know – by using whatever weapons they have at hand to gain what they need to stay alive. Adding to the problems of the poor, the Launceston and Western Railway Company, run by the colonizers, has recently accumulated large debts at the hands of speculators, and the Tasmanian government has just decided to make its citizens pay for those losses. Learning that the legislature has “voted to confiscate our property, steal our money, and make ruins of our lives,” large crowds gather to take matters into their own hands. “It is because they believe us weak,” they decide. “Because they believe the undue exercise of power over the supine and the insipid is their prerogative.” Resentment against the police is high, and the tempers of the poor and hungry are shorter than short.

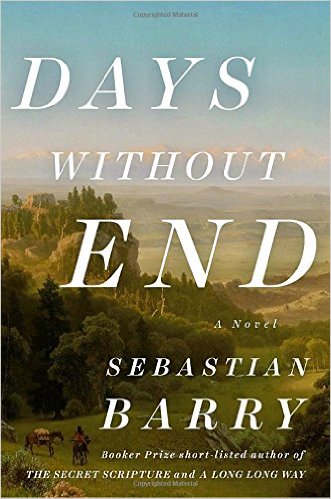

Escaping the Great Famine in Ireland, Thomas McNulty, a boy in his mid-teens and the only survivor of his family, hopes for a new start in a new world. Sneaking onto a boat for Canada with other starving Irish, many of whom die on board, he discovers, upon his arrival, that “Canada was a-feared of us…We were only rats of people. Hunger takes away what you are.” Seeing no future there, he travels, eventually, to the US, working his way to Missouri, where he then meets John Cole, another orphan boy of his own age, whose great-grandmother was an Indian. They connect instantly, and “for the first time I felt like a human person….John Cole was my love, all my love.” Realizing that they have a better chance of surviving together than they would have separately, they figure out a way to keep working until they are old enough to enlist in the U.S. Army. Once in the Army, they end up in northern California, where recent settlers have been having trouble with the Yurok Indians, native to those lands. The boys’ first battle is so savage and the outcome so devastating that Thomas describes it as “a complete vision of world’s end and death, in those moments I could think no more, my head bloodless, empty, racketing, astonished…We were dislocated, now we were ghosts.” Later they spend more years and more battles in Wyoming and eventually in Tennessee, where they fight for an Irish regiment against “the Rebs” in the Civil War.

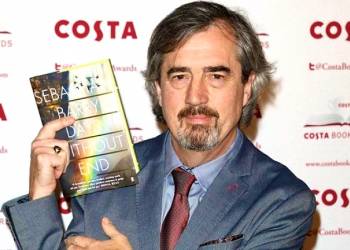

Escaping the Great Famine in Ireland, Thomas McNulty, a boy in his mid-teens and the only survivor of his family, hopes for a new start in a new world. Sneaking onto a boat for Canada with other starving Irish, many of whom die on board, he discovers, upon his arrival, that “Canada was a-feared of us…We were only rats of people. Hunger takes away what you are.” Seeing no future there, he travels, eventually, to the US, working his way to Missouri, where he then meets John Cole, another orphan boy of his own age, whose great-grandmother was an Indian. They connect instantly, and “for the first time I felt like a human person….John Cole was my love, all my love.” Realizing that they have a better chance of surviving together than they would have separately, they figure out a way to keep working until they are old enough to enlist in the U.S. Army. Once in the Army, they end up in northern California, where recent settlers have been having trouble with the Yurok Indians, native to those lands. The boys’ first battle is so savage and the outcome so devastating that Thomas describes it as “a complete vision of world’s end and death, in those moments I could think no more, my head bloodless, empty, racketing, astonished…We were dislocated, now we were ghosts.” Later they spend more years and more battles in Wyoming and eventually in Tennessee, where they fight for an Irish regiment against “the Rebs” in the Civil War. Sebastian Barry, a writer with almost unparalleled ability to control his characters, his story line, his style, and the peaks and valleys of the changing moods of his novel, succeeds brilliantly in this novel, already the winner of the Costa Award in the UK, and likely to be winner of several more major prizes, as well. Thomas McNulty, Barry’s main character, is shown in all his youth and vulnerability, but Barry never resorts to easy sentimentality in order to draw sympathy for him, no matter how horrific the circumstances in which Thomas finds himself. Life’s harsh conditions and Thomas’s lack of family have become his accepted “normal,” and the reader quickly identifies with him as he slowly recreates a “family” of sorts during the course of this often violent and bloody novel. John Cole, the first member to join his “family,” becomes his “rock,” and their relationship keeps both of them grounded during battle action and its attendant trauma which are the undoing of some older, less hopeful men.

Sebastian Barry, a writer with almost unparalleled ability to control his characters, his story line, his style, and the peaks and valleys of the changing moods of his novel, succeeds brilliantly in this novel, already the winner of the Costa Award in the UK, and likely to be winner of several more major prizes, as well. Thomas McNulty, Barry’s main character, is shown in all his youth and vulnerability, but Barry never resorts to easy sentimentality in order to draw sympathy for him, no matter how horrific the circumstances in which Thomas finds himself. Life’s harsh conditions and Thomas’s lack of family have become his accepted “normal,” and the reader quickly identifies with him as he slowly recreates a “family” of sorts during the course of this often violent and bloody novel. John Cole, the first member to join his “family,” becomes his “rock,” and their relationship keeps both of them grounded during battle action and its attendant trauma which are the undoing of some older, less hopeful men.

Born in Barbados, brought up in Nigeria, and now living in South Africa, author Yewande Omotoso may soon have to give up her profession. Trained as an architect and still working in that field, she has recently won the South African Literary Award for First Time Author and has been nominated for three other major South African prizes in the past four years. Her first novel, Bom Boy, was a popular, as well as literary, success, and this new novel looks as if it will appeal to the same kind of audience, readers looking for an escape from some of the doom and gloom of contemporary life but not an escape into mindlessness, a story with some realistic grit. In The Woman Next Door, her second novel, Omotoso’s vivid characters and devotion to telling a good story provide charm and the kind of humor which reveals her characters’ attitudes and states of mind, drawing in the reader and making the novel’s conflicts feel more like those that many of us face in our own lives. Setting the novel in Cape Town, South Africa, Omotoso depicts Katterijn, an upscale enclave which has not yet escaped the country’s past history of apartheid, however much the professionally successful neighbors might want to pretend that it no longer exists, but she is not a “message novelist.” For her, the story and its characters come first, her themes being revealed through their conflicts and the empathy she creates among her readers.

Born in Barbados, brought up in Nigeria, and now living in South Africa, author Yewande Omotoso may soon have to give up her profession. Trained as an architect and still working in that field, she has recently won the South African Literary Award for First Time Author and has been nominated for three other major South African prizes in the past four years. Her first novel, Bom Boy, was a popular, as well as literary, success, and this new novel looks as if it will appeal to the same kind of audience, readers looking for an escape from some of the doom and gloom of contemporary life but not an escape into mindlessness, a story with some realistic grit. In The Woman Next Door, her second novel, Omotoso’s vivid characters and devotion to telling a good story provide charm and the kind of humor which reveals her characters’ attitudes and states of mind, drawing in the reader and making the novel’s conflicts feel more like those that many of us face in our own lives. Setting the novel in Cape Town, South Africa, Omotoso depicts Katterijn, an upscale enclave which has not yet escaped the country’s past history of apartheid, however much the professionally successful neighbors might want to pretend that it no longer exists, but she is not a “message novelist.” For her, the story and its characters come first, her themes being revealed through their conflicts and the empathy she creates among her readers.

Having grown up in Gwangju, South Korea, where her brother still lives, author Han Kang writes of that city’s civil uprising of May, 1980, when she was ten years old, and the military’s reaction with all its attendant horrors. In that perennially restive southern city, many young people, most of them unarmed, were slaughtered at the hands of aggressive government soldiers, and when the battles ended, there were no clear victors. Just six months prior, President Park Chung-hee, a harsh dictator, was assassinated by the nation’s security services. He had ruled the country for eighteen years and was succeeded as President by Major General Chun Doo-Hwan, in April, 1980. The following month, Chun feared the possibility of a popular rebellion in Gwangju and quickly deployed the army there. By closing the university, he thereby freed many earnest, but untrained, young people who took to the streets to express their dissatisfaction with the new military government. Many were murdered.

Having grown up in Gwangju, South Korea, where her brother still lives, author Han Kang writes of that city’s civil uprising of May, 1980, when she was ten years old, and the military’s reaction with all its attendant horrors. In that perennially restive southern city, many young people, most of them unarmed, were slaughtered at the hands of aggressive government soldiers, and when the battles ended, there were no clear victors. Just six months prior, President Park Chung-hee, a harsh dictator, was assassinated by the nation’s security services. He had ruled the country for eighteen years and was succeeded as President by Major General Chun Doo-Hwan, in April, 1980. The following month, Chun feared the possibility of a popular rebellion in Gwangju and quickly deployed the army there. By closing the university, he thereby freed many earnest, but untrained, young people who took to the streets to express their dissatisfaction with the new military government. Many were murdered.