“They were standing in the middle of West Princes Street looking up at the blown-out windows and scorched sandstone of what had been the flat at number 43. The flats around had suffered too: cracked windows, torn curtains hanging out, a window box filled with daffodils sitting face down in the middle of the road…Glasgow [had always been] Belfast without the bombs…until now that is.”

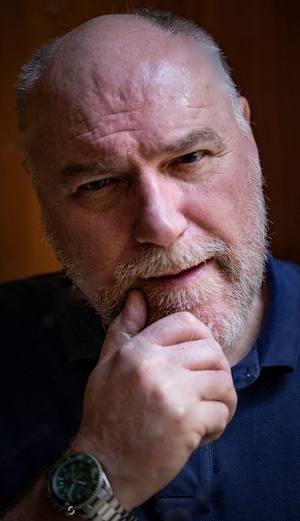

Set in Glasgow in the days between April 12, 1974 and April 22, 1974, this dark, mystery thriller by Alan Parks focuses on the dysfunctional aspects of life in one of Scotland’s major cities, one well known for its gangs and knife crime. According to research by Beltramian and Company,* it is “the least peaceful of all the major urban areas in the UK,” and though it has improved in the present day, “recent studies have found that up to 3,500 [young men] between the ages of 11 and 23 have joined one of the 170 street gangs within the city’s borders. Furthermore, the homicide rate for Glasgow males between 10 and 29 is comparable to rates of Argentina, Costa Rica and Lithuania.” Life in Glasgow is both difficult and dangerous, and author Alan Parks, a long-time resident, knows it well. Author of four novels set in Glasgow in the 1970s, Parks specializes in “Tartan Noir,” and brings this difficult city to life in each one, recognizing the horrors of violence and the underlying economic conditions which make any kind of “ordinary life” there a dark challenge. He sees life as it is and depicts it in all its grim reality.

Set in Glasgow in the days between April 12, 1974 and April 22, 1974, this dark, mystery thriller by Alan Parks focuses on the dysfunctional aspects of life in one of Scotland’s major cities, one well known for its gangs and knife crime. According to research by Beltramian and Company,* it is “the least peaceful of all the major urban areas in the UK,” and though it has improved in the present day, “recent studies have found that up to 3,500 [young men] between the ages of 11 and 23 have joined one of the 170 street gangs within the city’s borders. Furthermore, the homicide rate for Glasgow males between 10 and 29 is comparable to rates of Argentina, Costa Rica and Lithuania.” Life in Glasgow is both difficult and dangerous, and author Alan Parks, a long-time resident, knows it well. Author of four novels set in Glasgow in the 1970s, Parks specializes in “Tartan Noir,” and brings this difficult city to life in each one, recognizing the horrors of violence and the underlying economic conditions which make any kind of “ordinary life” there a dark challenge. He sees life as it is and depicts it in all its grim reality.

The novel opens with an explosion at a “shitey rented flat in Glasgow,” which the polis see as a bizarre attempt to strike at the British establishment. A superficial investigation indicates that there is one dead man, whom Harry McCoy and his partner Wattie decide was the bomber. It is not until Hughie Faulds, a cop from Belfast, shows up with his superior experience, that they learn details that show the victim was inexperienced and trying to make the bomb when it went off prematurely. Now the concern is that someone or some group may be making more bombs, a new problem for Glasgow. In the midst of this turmoil, an American man, Andrew Stewart, approaches McCoy. Stewart’s son Donald, a young American sailor assigned to the American naval base in Greenock, has gone missing. Young Donald is a shy man, not the adventurous type, and his father, a former navy captain, is frantic with worry.

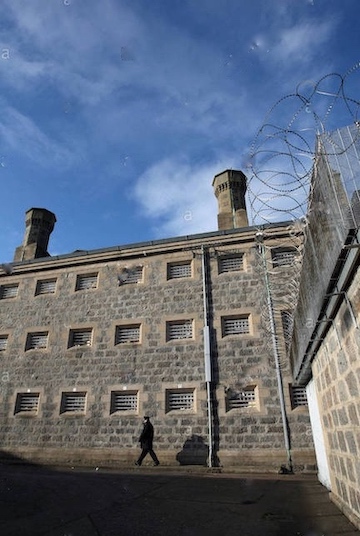

Since McCoy is about to leave for Aberdeen, he allows the father, who has traveled to Glasgow from Boston, to accompany him on the ride to tell his story. McCoy is going to Aberdeen Prison to pick up a friend, who “got into a wee bit of bother, nothing serious.” That man, a childhood friend named Stevie Cooper, has been badly beaten and kicked by the officers in the prison, perhaps because of his connection to a fight with Pat Dixon and his brother Jamsie, a man who is about to be sentenced to several years in prison for his violence and his problems in Glasgow. Connections between the prison officers, the police, and the crime lords of Glasgow are suggested, and Cooper seems connected to them. Adding to the narrative mix, Andrew Stewart represented the U.S. in boxing in the 1948 Olympics, and Stevie Cooper is a boxing promoter, and these two begin to spend time together.

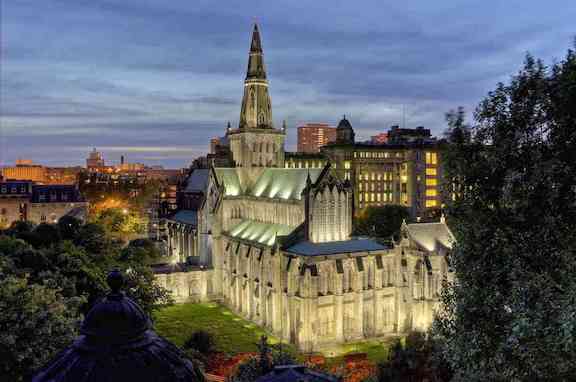

Then another explosion occurs, this one at the Glasgow Cathedral. As the various characters begin to interact more directly, McCoy begins to believe that Cooper may be involved in some of the troubles, perhaps in a big way. He also begins to believe that Donny Stewart, missing son of Andrew Stewart, might not be as timid as his father thinks he is. Murders take place, and some of McCoy’s non-police friends make suggestions regarding the possible guilt of various characters whom the reader has come to know. The possibility that the IRA is involved in some of the trauma further adds to the complexity and the international scope. Another bombing at a brewery leads to additional deaths, and some evidence suggests that one or more private groups, including a commune, may, in reality, be private military groups with their own set of governmental goals. A hoard of old photos showing men being tortured, perhaps by the British army, adds a new element of horror and raises questions regarding the people responsible for the photos and their own possible involvement in the crimes McCoy is investigating.

By far the most complex of the three McCoy novels I have read so far, The April Dead features approximately forty characters, some of them present for much of the book and some merely for short scenes. Keeping a character list saves a lot of page-flipping as these characters appear and reappear (or not). The overall mood throughout is high pressured and tense, and the novel lacks any kind of comic relief or even the relief of seeing some major issues become successfully resolved before the conclusion. The deaths keep coming, and while the perpetrators may seem obvious to some characters and the reader, those who are really responsible always seems to remain a mystery. One factor which makes the mood particularly depressing is that there are almost no women in the book – for good or for bad – and the chance for a break from the super-macho behavior of the police, the military, and the criminal elements never occurs. When McCoy himself ultimately manipulates some of the evidence to achieve an end he personally deems to be “right,” the depths to which one good man will stoop for the “right” result are laid out for the world to see, if anyone still has any questions. With non-stop action, constant surprises, deaths and near-deaths, torture, torment, and evil involving virtually all the “good” institutions civilization counts on for its existence, Alan Parks raises some thought-provoking issues on many levels. More loosely connected, plot-wise, than previous McCoy novels, The April Dead will still appeal to Parks’s many Tartan noir fans, while others may hope that the author eventually expands his characterizations to include one or two who find a ray of hope even amidst the horrors.

* Note: Beltramian and Company has published its information about Glasgow here: https://www.beltramiandcompany.co.uk

ALSO by Parks: BLOODY JANUARY , BOBBY MARCH WILL LIVE FOREVER, MAY GOD FORGIVE

Photos: The photo of the Greenock Naval Station appears on: https://www.bbc.com

The Prison in Aberdeen, where McCoy picked up Stevie Cooper: https://www.alamy.com

Glasgow Cathedral, one of the bombing sites: https://www.tripsavvy.com

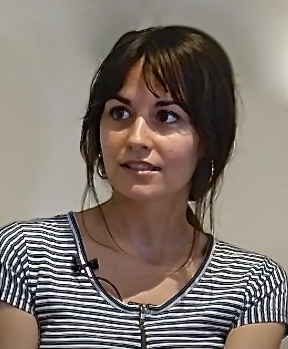

Author Alan Parks: https://www.shutterstock.com

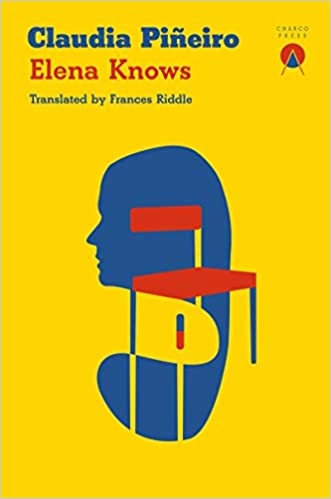

Suffering from a debilitating illness which limits her movement, Elena, an Argentinian mother in her sixties, has decided she will need help in resolving the death of her daughter Rita, assumed by police and investigators to have been a suicide.

Suffering from a debilitating illness which limits her movement, Elena, an Argentinian mother in her sixties, has decided she will need help in resolving the death of her daughter Rita, assumed by police and investigators to have been a suicide.

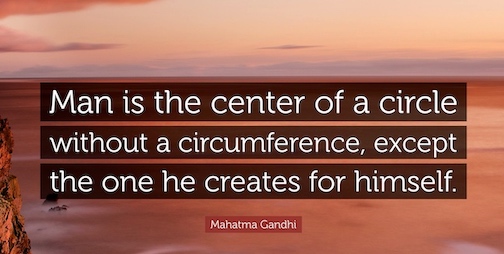

This image of the circle becomes the focus of

This image of the circle becomes the focus of

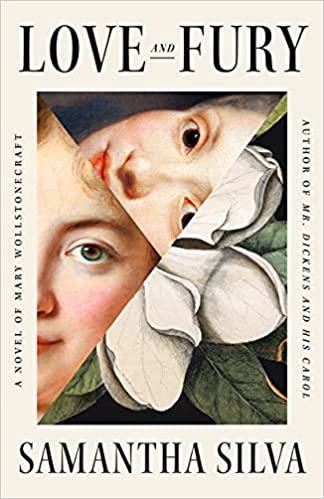

Though Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797) may have been afraid to “unleash her story into the world,” that story, however incomplete it may have seemed to the general public in her own time, has now been recreated in insightful detail by author Samantha Silva.

Though Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797) may have been afraid to “unleash her story into the world,” that story, however incomplete it may have seemed to the general public in her own time, has now been recreated in insightful detail by author Samantha Silva.

In this absorbing and constantly surprising metafictional novel,Yugoslavian author Lana Bastašić tells the history of a complex friendship between two women from their early years as children in Bosnia through their schooling, part of their college years, and ultimately when they are in their early thirties.

In this absorbing and constantly surprising metafictional novel,Yugoslavian author Lana Bastašić tells the history of a complex friendship between two women from their early years as children in Bosnia through their schooling, part of their college years, and ultimately when they are in their early thirties.