“He wanted only one thing, to honour Arabic script, that divine invention that made a few written characters into oceans, deserts, and mountains, that moved the heart and inspired the mind…Script was a goddess, and only a man who gave up everything for it would be let into Paradise.”—passing thoughts of Hamid Farsi.

Set in Damascus, Syr ia, from 1931 through 1956, The Calligrapher’s Secret seems, on the surface, to be an impressionistic and romantic novel which strolls at its own leisurely pace, dropping in on first one character and then another, moving back and forth in time and across ethnic, religious, and social groups. Several main characters and families share their lives and problems, and, in the process, convey an intimate picture of life in Damascus, filled with vibrant descriptions of the city, its neighborhoods, and its varied social life. The novel is much more than a series of little domestic stories, however charming and interesting those may sometimes be. It is also a serious exploration of the issues surrounding Arabic calligraphy, issues so serious that some who want to make Arabic script more modern, so it can accommodate new words from science and philosophy, face death threats and personal attacks by traditionalists. They consider the language of the Quran the word of God, to be sacred, inviolable, unchanging.

ia, from 1931 through 1956, The Calligrapher’s Secret seems, on the surface, to be an impressionistic and romantic novel which strolls at its own leisurely pace, dropping in on first one character and then another, moving back and forth in time and across ethnic, religious, and social groups. Several main characters and families share their lives and problems, and, in the process, convey an intimate picture of life in Damascus, filled with vibrant descriptions of the city, its neighborhoods, and its varied social life. The novel is much more than a series of little domestic stories, however charming and interesting those may sometimes be. It is also a serious exploration of the issues surrounding Arabic calligraphy, issues so serious that some who want to make Arabic script more modern, so it can accommodate new words from science and philosophy, face death threats and personal attacks by traditionalists. They consider the language of the Quran the word of God, to be sacred, inviolable, unchanging.

These two different focuses of the novel are ostensibly connected through the life of Hamid Farsi, a calligrapher who is dedicated to making the modernization of Arabic script possible, even as his personal life, his relationships, and his unsatisfactory marriage to a beautiful young woman are unfolding and entertaining the reader. The complications in these intertwining tales of love, family life, and daily survival often seem to occur almost at random, with the novel sometimes leaping years ahead to foretell endings, then backing up to fill in the blanks. The more intellectual (and more interesting) issues regarding script and calligraphy are almost exclusively the province of Hamid Farsi, and they seem to float on a different plane above most of the many domestic plots of the novel, with a treatise explaining the religious issues about script appearing at the end.

The novel opens in summer, 1 957, and Noura, the twenty-year-old wife of Hamid Farsi, one of the most esteemed calligraphers in Damascus, has run away. Backing up to 1942, the novel then reveals her family and life at that time. Her father, Sheikh Rami Arabi, a famous scholar, bemoans the lack of religious feeling among some of his students: “They treat God like a waiter in a restaurant. They order rain, and as soon as he brings them their order, they turn their backs on him.” An episode in which a gang torments a Christian by pulling down his pants in public gives some insight into ethnic issues with which everyone is dealing. Noura’s schooling, which she loves, as opposed to the lack of schooling available for a poor Christian boy named Salman, who is taught to read and write by a bright young female friend, emphasizes class differences and the difference in opportunities.

957, and Noura, the twenty-year-old wife of Hamid Farsi, one of the most esteemed calligraphers in Damascus, has run away. Backing up to 1942, the novel then reveals her family and life at that time. Her father, Sheikh Rami Arabi, a famous scholar, bemoans the lack of religious feeling among some of his students: “They treat God like a waiter in a restaurant. They order rain, and as soon as he brings them their order, they turn their backs on him.” An episode in which a gang torments a Christian by pulling down his pants in public gives some insight into ethnic issues with which everyone is dealing. Noura’s schooling, which she loves, as opposed to the lack of schooling available for a poor Christian boy named Salman, who is taught to read and write by a bright young female friend, emphasizes class differences and the difference in opportunities.

A young orphan boy, provided with a home by the Catholic Church, finds his only work in the baths, where Salman also finds work, though sexual abuse is common there. Eventually, Noura is married to Hamid Farsi, an older widower, the wedding preparations being particularly interesting in their details, though Noura is miserable in her marriage from the outset. When Salman eventually (and coincidentally) gets a job as errand boy for Hamid Farsi, the stage is set for the blossoming of love with Noura, and their eventual running away (which we have known since page three). Before that happens, however, there are other complications, some involving Nasri Abbani, a wealthy skirt chaser with four wives, four children a year, ten houses and three regular prostitutes. Abbani sees Noura from a distance and becomes obsessed with her, and he eventually becomes involved in the life of Hamid Farsi, not only because of Noura but because of sinister connections he has to people who oppose any change to Arabic script, which Hamid Farsi is pursuing.

Numerous overlapping su bplots keep the reader entertained, but at several places in the novel, I asked myself where all this was going. At four hundred forty-four pages, this is a long book, and I am not sure that the family backgrounds of the parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, wives, prostitutes, and employees of the main characters are all necessary to advancing the plot or giving a lively picture of life in Damascus. Then again, the plot itself is not really a plot as one may be accustomed to knowing it. Rather it is a series of subplots, and though these are often connected, they are not unified or connected in the traditional sense. Noura and Salman, responsible for the love story, disappear, and nothing more is heard of them for almost a hundred fifty pages. Instead, the novel devolves into an analysis of aspects of Arabic script, the Sunni/Shiite conflicts about language, and conflicts between traditionalists and. progressives which have apparently rent the Arab world.

bplots keep the reader entertained, but at several places in the novel, I asked myself where all this was going. At four hundred forty-four pages, this is a long book, and I am not sure that the family backgrounds of the parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, wives, prostitutes, and employees of the main characters are all necessary to advancing the plot or giving a lively picture of life in Damascus. Then again, the plot itself is not really a plot as one may be accustomed to knowing it. Rather it is a series of subplots, and though these are often connected, they are not unified or connected in the traditional sense. Noura and Salman, responsible for the love story, disappear, and nothing more is heard of them for almost a hundred fifty pages. Instead, the novel devolves into an analysis of aspects of Arabic script, the Sunni/Shiite conflicts about language, and conflicts between traditionalists and. progressives which have apparently rent the Arab world.

I confess, however, that the issues regarding language are among the most interesting that I have read in years. If someone believes that the Quran is the word of God and that its language is sacred, does that also mean that no new word can be added to the lexicon even fifteen hundred years later? And since almost every Arabic word has a hundred synonyms and four variations of form per word, depending on whether a letter/sound occurs at the beginning, middle, or end of a word, can true communication really take place either within the academic world in the Middle East or with the “outside” world of the west? Isn’t there any value at all in sharing knowledge? Or are the language issues so important to Islamic scholars that they will reject the opportunity to share new ideas because they cannot be translated into “new” Arabic script? If the issues raised here in this 1950s setting have not yet been resolved, they may explain why so few academic studies from the Arab world make their way into print in the west—and maybe why they may not make it into print in their own countries. A fascinating reading experience, though the book itself defies the customary structure of the novel.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo accompanies an interview here: http://www.dradio.de He has been living in Germany since 1971.

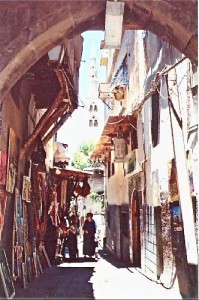

The photo of Damascus is from http://www.advancedtravel.org

The Damascus street scene is from http://members.virtualtourist.com

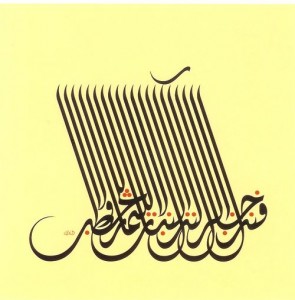

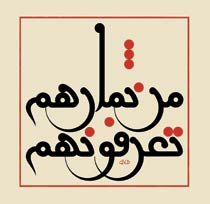

The first calligraphy is from http://imad_moustapha.blogs.com, the journal of Imad Moustapha, Syria’s envoy to the US, which also has examples of many other wonderful Syrian works.

The second calligraphy may be found in the British Museum: http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk, “By Their Fruits Shall You Know Them.”