Note: This novel by Irish author Sebastian Barry was WINNER of the Costa Award for Best Novel of 2016 in the UK and Ireland.

“Don’t tell me a Irish is an example of civilized humanity. He may be an angel in the clothes of a devil or a devil in the clothes of an angel but either way you’re talking to two when you talk to one Irishman….I seen killer Irishmen and gentle souls but they’re both the same, they both have an awful fire burning inside them, like they were just the carapace of a furnace.” – Thomas McNulty, a 17-year-old Irishman in the U. S. Army, 1850s.

Escaping the Great Famine in Ireland, Thomas McNulty, a boy in his mid-teens and the only survivor of his family, hopes for a new start in a new world. Sneaking onto a boat for Canada with other starving Irish, many of whom die on board, he discovers, upon his arrival, that “Canada was a-feared of us…We were only rats of people. Hunger takes away what you are.” Seeing no future there, he travels, eventually, to the US, working his way to Missouri, where he then meets John Cole, another orphan boy of his own age, whose great-grandmother was an Indian. They connect instantly, and “for the first time I felt like a human person….John Cole was my love, all my love.” Realizing that they have a better chance of surviving together than they would have separately, they figure out a way to keep working until they are old enough to enlist in the U.S. Army. Once in the Army, they end up in northern California, where recent settlers have been having trouble with the Yurok Indians, native to those lands. The boys’ first battle is so savage and the outcome so devastating that Thomas describes it as “a complete vision of world’s end and death, in those moments I could think no more, my head bloodless, empty, racketing, astonished…We were dislocated, now we were ghosts.” Later they spend more years and more battles in Wyoming and eventually in Tennessee, where they fight for an Irish regiment against “the Rebs” in the Civil War.

Escaping the Great Famine in Ireland, Thomas McNulty, a boy in his mid-teens and the only survivor of his family, hopes for a new start in a new world. Sneaking onto a boat for Canada with other starving Irish, many of whom die on board, he discovers, upon his arrival, that “Canada was a-feared of us…We were only rats of people. Hunger takes away what you are.” Seeing no future there, he travels, eventually, to the US, working his way to Missouri, where he then meets John Cole, another orphan boy of his own age, whose great-grandmother was an Indian. They connect instantly, and “for the first time I felt like a human person….John Cole was my love, all my love.” Realizing that they have a better chance of surviving together than they would have separately, they figure out a way to keep working until they are old enough to enlist in the U.S. Army. Once in the Army, they end up in northern California, where recent settlers have been having trouble with the Yurok Indians, native to those lands. The boys’ first battle is so savage and the outcome so devastating that Thomas describes it as “a complete vision of world’s end and death, in those moments I could think no more, my head bloodless, empty, racketing, astonished…We were dislocated, now we were ghosts.” Later they spend more years and more battles in Wyoming and eventually in Tennessee, where they fight for an Irish regiment against “the Rebs” in the Civil War.

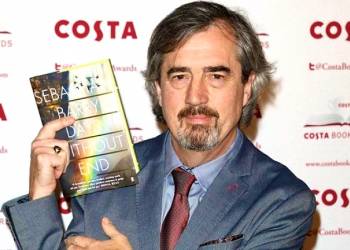

Sebastian Barry, a writer with almost unparalleled ability to control his characters, his story line, his style, and the peaks and valleys of the changing moods of his novel, succeeds brilliantly in this novel, already the winner of the Costa Award in the UK, and likely to be winner of several more major prizes, as well. Thomas McNulty, Barry’s main character, is shown in all his youth and vulnerability, but Barry never resorts to easy sentimentality in order to draw sympathy for him, no matter how horrific the circumstances in which Thomas finds himself. Life’s harsh conditions and Thomas’s lack of family have become his accepted “normal,” and the reader quickly identifies with him as he slowly recreates a “family” of sorts during the course of this often violent and bloody novel. John Cole, the first member to join his “family,” becomes his “rock,” and their relationship keeps both of them grounded during battle action and its attendant trauma which are the undoing of some older, less hopeful men.

Sebastian Barry, a writer with almost unparalleled ability to control his characters, his story line, his style, and the peaks and valleys of the changing moods of his novel, succeeds brilliantly in this novel, already the winner of the Costa Award in the UK, and likely to be winner of several more major prizes, as well. Thomas McNulty, Barry’s main character, is shown in all his youth and vulnerability, but Barry never resorts to easy sentimentality in order to draw sympathy for him, no matter how horrific the circumstances in which Thomas finds himself. Life’s harsh conditions and Thomas’s lack of family have become his accepted “normal,” and the reader quickly identifies with him as he slowly recreates a “family” of sorts during the course of this often violent and bloody novel. John Cole, the first member to join his “family,” becomes his “rock,” and their relationship keeps both of them grounded during battle action and its attendant trauma which are the undoing of some older, less hopeful men.

This small painting (16″ x 11″) by Henry Farny (1847 -1916) from 1894 shows a Southern Warrior in his formal dress.

Much of the novel is told through flashbacks, and Thomas admits that he sometimes may have minor details wrong. He jumps around as he remembers events, and he makes no distinction between the barbarity of the Indian wars as opposed to the American Civil War. There is no difference, the author is saying – one war blends into the next, regardless of whether the participants are of different cultures. Despite all, however, Thomas continues to hope and dream. His “family” gets larger when John becomes an adoptive father. Later, when Thomas and John are away fighting the Civil War, the child’s caretaker becomes the equivalent of a grandfather for the child and a father figure for Thomas and John. The child gives new meaning to life for all of them while also learning the nature of responsibility and honor. On a larger scale, Major Neale, leader of the regiment to which Thomas and John belong, suffers great personal losses and arouses sympathy in Thomas. Caught-His-Horse-First, an Indian chief, also suffers similar losses, creating a sense of sad universality as these individual losses affect their individual judgment and their actions.

Battle scene by Don Troiani shows the harp and shamrock insignia of the Irish Brigade during the Civil War. Click and scroll to enlarge.

Irony adds to the thematic message. Thomas, like most of the other soldiers in his regiment, is Irish, and during the Civil War, their regimental flag bears the shamrock and harp. In their first big battle, they discover that “the Rebs” they are fighting are also carrying the same flag, though they fight each other, making both sides wonder why. At another point during the war, a captain in Thomas’s regiment takes issue with the murderous intent of the major’s orders and the graphically depicted barbarity which results, proving that both sides are acting like animals. In time, Thomas himself is forced to take action against one of his own men, but unlike them, he takes no joy at taking a life to save that of another. Depictions of the collecting of trophies from the enemy will make every reader question the innate nature of humanity. The themes of love and war become fully developed as additional scenes show the interconnections between power and weakness, honor and cowardice, empathy and cold-blooded aggression, selflessness and sacrifice.

The Confederate Bowie knife (with its 13″ blade) was a killer instrument during the Civil War, often responsible for more deaths than rifles.

Throughout the novel, Barry seems to do the impossible, combining his naturally lyrical style with subject matter which is often tough, sometimes brutal, and never lovely. Yet he makes it work. One battle takes place amidst great noise, but Thomas notes that “There’s all these little humpy hills and stands of scrubby trees, and then the full dark river pouring south on our left. Friendly, protecting river.” When he sees the Rebs, he comments, “how thin these boys are, how strange, like ghosts and ghouls. Their eyes like twenty thousand dirty stones. River stones.” After the battle, a particularly large man, has “run his big form so heavy he’s fallen over like a killed man. I can hear him muttering into the earth, his mouth and face plastered in mud. The day is as dry as a furnace but his sweat makes mud enough to throw a pot.” And after the battle, “the whole body of men seems to be sleeping. No force will ever rouse us again. Our eyes are closed and we are asking for our strength returned. If we got Gods we’re praying to them. Then it seeps back. No thankful speech of any captain could be so deep as the relief of it.” Barry makes it all real in a novel which Kazuo Ishiguro describes as “the most fascinating line-by-line first-person narration I’ve come across in years,” and which Donal Ryan calls “a beautiful, savage, tender, searing work of art. Sentence after perfect sentence, it grips and does not let go.” #1 on my Favorites List for 2017.

ALSO by Barry: ON CANAAN’S SIDE and A THOUSAND MOONS

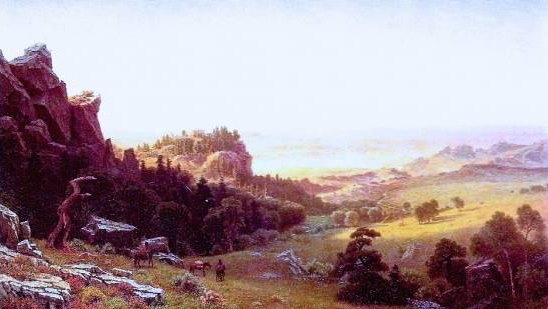

This landscape by Alfred Bierstadt (1830 – 1902), “View from Wind River Mountains,” is used as the cover for the US edition of this book. Most of the detail is from the left side of the painting.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://en.mogaznews.com/

The photo of the “Southern Plains Indian Warrior,” appears on https://www.pinterest.com Bonham’s, an auction house in England, says: “On one of our appraisal events, we consigned a painting that was originally bought from a garage sale for $15,” Sanchez said. “We estimated the painting at $100,000 to $150,000 and it ended up selling for $361,500 including buyer’s premium. That painting was “Southern Plains Indian warrior,” by Henry Farny, part of a featured lot in Bonhams’ California and Western paintings and sculpture auction in May 2012.

The battle scene by Don Troiani, showing the flag of the Irish Brigade, appears on http://civilwartalk.com

The Confederate Bowie knife, with its wooden grips and 13″ blade, was responsible for almost as many deaths as the rifle. http://www.civilwar.si.edu

“View from Wind River Mountains” by Albert Bierstadt is shown on http://www.ebay.com