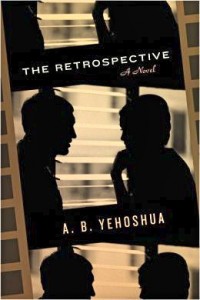

Note: This novel was WINNER of the French Prix Medicis Etranger for Best Novel Published in Translation.

“[At the Jerusalem Theatre], someone recognizes [director Yair Moses]. They are actors and singers and dancers here for the dress rehearsal of a musical play for children…

“A play? By whom, about what?” Moses asks.

“Based on Don Quixote, adapted to an Israeli setting.”

“More Don Quixote?” sniffs Moses. “Enough is enough, no? The eternal hero.”

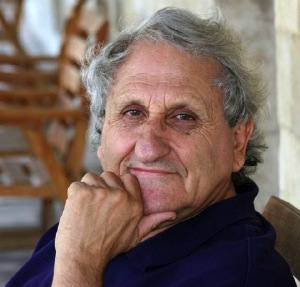

In this age of sound bites and tweets, few novelists devote hundreds of pages to the creation of thoughtful and insightful novels of ideas concerned with major philosophical and moral issues. Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua is just such an author, however, creating a surprising novel which ranges widely, as it examines such issues as reality vs. the recreation of reality through art and film and myth; life, as opposed to the afterlife, and whether the afterlife is real or imagined; the actualities of the past vs. memories of the past; the concept of guilt and whether one can atone; and the many aspects of love – love and death, love and hatred, love and jealousy – as it controls our actions (and even our politics).

In this age of sound bites and tweets, few novelists devote hundreds of pages to the creation of thoughtful and insightful novels of ideas concerned with major philosophical and moral issues. Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua is just such an author, however, creating a surprising novel which ranges widely, as it examines such issues as reality vs. the recreation of reality through art and film and myth; life, as opposed to the afterlife, and whether the afterlife is real or imagined; the actualities of the past vs. memories of the past; the concept of guilt and whether one can atone; and the many aspects of love – love and death, love and hatred, love and jealousy – as it controls our actions (and even our politics).

The development of these ideas, revealed through the novel’s actions and symbols, also applies to contemporary Israel – the violence between residents of Gaza and Israel; the various branches of Judaism with their different interpretations of their obligations; the parallels between Spain and its Sephardic Jews, attacked and killed during the Inquisition, and Jews who were attacked during the Holocaust; and the contrasts of the devout Catholic priests with whom Moses associates in Spain and the crass behavior of Moses himself when they grant him a prize. Obviously, this novel is challenging (and occasionally slow moving), providing much to ponder as important concepts unfold. Virtually every detail adds to the author’s depiction of one or more of the novel’s big ideas.

The story line itself is not complicated. Famous Israeli director Yair Moses has received an unexpected invitation to attend a retrospective of his films to be held in Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain. He arrives from Israel with Ruth, an aging actress whom he regards more as a character in his films than as a real person. He soon discovers that the three films to be shown the first day, and all the succeeding films, are his earliest films, each made with the help of a brilliant screenwriter, Shaul Trigano, one of his former students.

As the seven films shown at the retrospective are described successively by the author, the reader becomes familiar with some of their themes and how they are developed. The dramatic changes between these early films and Yair Moses’s films of the past twenty years become obvious, however, when Juan de Viola, the priest who is also the institute’s host and guide, comments: “It seems to us, Mr. Moses, that in the past two decades you have turned your back on the surrealistic and symbolic style of your early films and have become addicted to extreme realism that is almost naturalistic…Why? Do you no longer believe in a world of transcendence, in what is hidden, invisible, and fantastic, so much so that you are mired in the mundane and obvious?” A young teacher follows up this question: “There is a feeling, sir, that in your latest films, the material aspect has assumed supreme importance, and not necessarily out of a new aesthetic. As if you are sanctifying the materialism of the world or succumbing to it…Does not such naturalistic realism smother the possibility of mystery, of rising to a higher vision?”

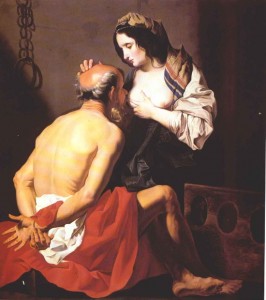

All of this change has occurred in the films made after Moses and screenwriter Trigano disagreed regarding a key scene which Ruth refused to play. Moses sided with Ruth, leading to a permanent break with Trigano and Trigano’s departure from film-making. The strange scene in question, which is also the subject of a painting on the wall behind Moses’s bed at the hotel, was to be a re-enactment of an ancient story dating from 30 A.D., one so well known in those days that it has even been found painted on a wall in Pompeii. It is the story of “Caritas Romana,” or “Roman Charity,” reflecting the horrifying plight of Cimon, an old man who has been sentenced to death by starvation. His daughter Pero, who has just given birth, visits her father in prison, and seeing his condition, and wanting to save his life, she offers him her breast and then suckles him. When her actions become known and publicized by the jailer, she is seen as a heroine, the epitome of the devoted daughter. For her love and care, her father is pardoned. For screenwriter Trigano, this scene was intended to be the high point of the film, with every other action dependent upon it, a scene of such importance and significance, such “depth and timelessness in its theme…[that it would] enrich the arts for generations.”

As Yehoshua further expands on “Caritas Romana,” its symbolism for Trigano becomes obvious, and Trigano’s eventual, and seemingly bizarre, demand of Moses as a proper atonement for Moses’s failure to film the scene becomes understandable, at least on the level of its symbolism. Trigano believes that “There is no disgrace in art…Art makes the disgraceful beautiful and the repulsive meaningful. ” For the reader, however, there is no getting around the father/daughter action in the dominant scene of “Caritas Romana,” a subject so far from “normal” in our own society that identifying with it as “beautiful” is difficult, if not impossible. Though I could appreciate what Trigano was saying and understand how someone totally invested in aesthetics might find this beautiful, it did not really work for me as a scene of life-changing magnificence.

The novel is rich in detail, ideas, and symbolism, and the author’s narrative is both energizing and exciting in its possibilities. Its fine organization allows information about the characters to be revealed gradually. Like so many other novels of ideas, however, it subordinates characters and their lives to the overall structure in order to clarify and illustrate philosophical and thematic ideas. As a result, the characters become vehicles, rather than living, breathing “humans” as they move in and out of their films and their “reality,” which is, of course, reality as depicted in an imaginative and unusual piece of fiction. The final two or three pages, which tie up some loose ends, do fit the novel thematically and do draw on a long literary tradition, but in this context with Moses, unfortunately, they felt facile and even a bit clichéd to me.

ALSO by Yehoshua: A WOMAN OF JERUSALEM and FRIENDLY FIRE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.thebestwriters.com

The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela is from http://www.bestourism.com

The picture of “Caritas Romana,” by Matthias Meyvogel, an artist from 17th century Dutch Zeeland, a copy of which is on the wall behind the bed in Moses’s hotel room, appears on http://www.internetlooks.com. Both Rubens and Caravaggio also painted this scene in the early seventeenth century. The Pompeii version from 45 – 79 A.D. (not pictured here) may be seen on: http://en.wikipedia.org

The Tomb of St. James, which Moses passes on his way to confession with Manuel de Vega, may be found here:

http://www.turnbacktogod.com

The Jerusalem Theatre, by Avishai Teicher, appears on http://commons.wikimedia.org/

The map of Israel, with Netivot highlighted, is from

http://www.theisraelproject.org