“My husband and I are like two strangers who happen to meet coming out of a clinic where they have received treatment involving some physical unpleasantness. Both embarrassed, reading each other’s minds, conscious of an uneasy, embarrassing intimacy, wearily groping for the right tone in which to address each other.”

Hannah Gonen is only thirty when she makes this observation about her husband Michael. A young woman living in Jerusalem in the late 1950s, she has been married for ten years to a man she pursued and married when she was in her first year at the university and he was a graduate student. Michael, who describes himself to Hannah as “good…a bit lethargic, but hard-working, responsible, clean, and very honest,” eventually earns his PhD. degree in geology and begins work at the university, but Hannah, who has given up her literature studies upon her marriage, soon finds married life—and Michael himself—to be tedious. Her only child resembles Michael in personality, a child rooted in reality, who “finds objects much more interesting than people or words.”

Hannah Gonen is only thirty when she makes this observation about her husband Michael. A young woman living in Jerusalem in the late 1950s, she has been married for ten years to a man she pursued and married when she was in her first year at the university and he was a graduate student. Michael, who describes himself to Hannah as “good…a bit lethargic, but hard-working, responsible, clean, and very honest,” eventually earns his PhD. degree in geology and begins work at the university, but Hannah, who has given up her literature studies upon her marriage, soon finds married life—and Michael himself—to be tedious. Her only child resembles Michael in personality, a child rooted in reality, who “finds objects much more interesting than people or words.”

Writing in short, factual sentences, which come alive through his choice of details, author Amos Oz, often mentioned as a Nobel Prize candidate, recreates Hannah’s story of her marriage, a marriage which may or may not survive. Hannah and Michael married in 1949, shortly after Israel gained its independence, and the author often uses Hannah’s battles for independence and control of her life to reflect the growing pains of a new land, determined  to defend itself and protect its integrity. As their family backgrounds unfold, the personalities of Hannah and Michael and their behavior within the marriage are seen in a wider context. Hannah, who yearns for excitement, draws on her rich store of childhood memories and often escapes into a dream world. Michael, hard-working and pragmatic, remains a geologist, firmly connected to the earth.

to defend itself and protect its integrity. As their family backgrounds unfold, the personalities of Hannah and Michael and their behavior within the marriage are seen in a wider context. Hannah, who yearns for excitement, draws on her rich store of childhood memories and often escapes into a dream world. Michael, hard-working and pragmatic, remains a geologist, firmly connected to the earth.

After their child is born, a year after the marriage, it is Michael who usually takes care of him and washes his diapers. Hannah, mired in depression, says she is “contracted, withdrawn into myself as though I had lost a tiny jewel on the sea bed.” Gradually, she becomes more and more unstable, more and more depressed and hysterical, until she makes herself ill, a condition which she sees, ironically, as offering her some freedom. “I had lost my powers of alchemy, the ability to make my dreams carry me over the dividing line between sleeping and waking,” she explains. Despite Hannah’s self-pity and hysteria, Michael, the logical, reliable, unexciting husband retains his composure, so much so that Hannah wonders, “When will this man lose his self-control? Oh, to see him just once in a panic. Shouting for joy. Running wild.”

As the marriage and Hannah’s sanity appear to deteriorate, the author’s use of symbols gives depth and universality to the story. Hannah often imagines a glass dome over herself and her family, and wishes only that it remain transparent, not cloudy. She remembers the childhood games she played with Arab twins in her neighborhood, bossing them around, and she now fears they will wreak their vengeance on her. She imagines warships and a search for Moby Dick on the Nautilus. Even the changing seasons parallel Hannah’s state of mind, with much of her story taking place in the autumn.

As the marriage and Hannah’s sanity appear to deteriorate, the author’s use of symbols gives depth and universality to the story. Hannah often imagines a glass dome over herself and her family, and wishes only that it remain transparent, not cloudy. She remembers the childhood games she played with Arab twins in her neighborhood, bossing them around, and she now fears they will wreak their vengeance on her. She imagines warships and a search for Moby Dick on the Nautilus. Even the changing seasons parallel Hannah’s state of mind, with much of her story taking place in the autumn.

Rich with imagery and dense with symbols, this novel, first published in 1968 and recently republished in paperback, depicts two characters who deal in different ways with crises in their lives and marriage. Though the novel is set in Jerusalem about fifty years ago, the issues with which these characters are dealing are as pertinent today as they were then, and the emotional implications are as affecting . Psychologically true, the novel achieves rare universality, even though the reader may not empathize completely with Hannah, who is so often self-indulgent, or Michael, who, though reliable and honest, has so little imagi nation. Beautifully realized, My Michael, which shows Hannah’s possessiveness and need for control even in the title, depicts an immature woman who does not know who she herself is when she joins her life to that of someone else. Whether she and Michael learn to move beyond themselves is for the reader to decide.

nation. Beautifully realized, My Michael, which shows Hannah’s possessiveness and need for control even in the title, depicts an immature woman who does not know who she herself is when she joins her life to that of someone else. Whether she and Michael learn to move beyond themselves is for the reader to decide.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Natalia O’Hara, appears on http://www.praguepost.com

The photo of Jerusalem at sunset is from http://grahamsdownunderthoughts.blogspot.com

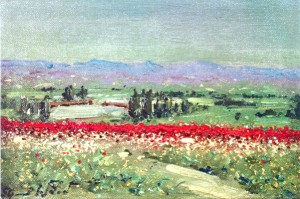

The painting of “Kibbutz Kfar Ruppin, 1950” is by Ludwig Blum (1891 – 1974), known as the “Painter of Jerusalem.” It is part of an exhibition held at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York from October 28, 2011 – January 15, 2012. http://mobia.org

ALSO by Amos Oz: A PANTHER IN THE BASEMENT (on my list of All-Time Favorites), SOUMCHI, THE RHYMING LIFE AND DEATH, A TALE OF LOVE AND DARKNESS and SCENES FROM VILLAGE LIFE, JUDAS