Note: This book has just been named WINNER of the Plutarch Award for Best Biography of 2019.

“Living a secret life meant never relaxing for a moment, and always having an explanation worked out. Those who survived for any time were wily, with a highly developed sixth sense. When entering a building Virginia could feel danger just by looking at the concierge, and she knew to listen at the door for unexpected voices before she went in. One mistake made in tiredness or haste could result in disaster.”

Sonia Purnell’s biography of Virginia Hall honors an American woman whose war-time exploits from 1940 – 1945 were so well planned, so well executed, and so successful in saving lives that she was honored by three countries for her efforts.

Sonia Purnell’s biography of Virginia Hall honors an American woman whose war-time exploits from 1940 – 1945 were so well planned, so well executed, and so successful in saving lives that she was honored by three countries for her efforts.

The French Croix de Guerre Avec Palme was her first, almost secret, award, an award she hid so well from the public that biographer Purnell spent years searching archives before she could confirm that it had been made at all. The British government named her an honorary member of the Order of the British Empire. Ultimately, she received the US Distinguished Service Cross from Gen. William Joseph “Wild Bill” Donovan, though she refused to have a formal ceremony at which President Truman would have presented the award to her publicly, for fear of endangering people who worked for her, and jeopardizing any future work she might be assigned for new, secret projects. Hall’s work in France for the British SOE (Special Operations Executive) and the American OSS (Office of Strategic Services), had put her in touch with organizations and spies from two countries as they fought the Nazis and the French Vichy government, and she had managed to remain almost anonymous because she “operated in the shadows, and that was where she was happiest.”

Born into an upper middle-class family in Baltimore, Virginia Hall graduated from private schools, a highly popular student there for her unconventional attitudes and her leadership capabilities. Always independent, she attended both Radcliffe and Barnard Colleges, the women’s colleges associated with Harvard and Columbia, and George Washington University, where she studied French, German, and Italian, though she did not graduate. Deciding to continue her education in Europe, she moved to Paris in 1926, in time to enjoy the Roaring Twenties, where she quickly made connections with artists and writers, intellectuals and politicians. In 1927, she moved to Vienna to continue her studies, adding Russian to her language skills, and it was there that she was able to observe the growth of fascism, political unrest, and Hitler’s National Socialist Party in action. In 1931, she accepted jobs in consular offices in Poland and Turkey, and it was in Turkey, on a hunting trip, that she fell and shot herself in the leg, an accident which required an amputation below the knee and the use of a prosthesis for the rest of her life. Later assignments in Poland and Estonia further expanded her language skills, but after eight years working for the foreign service and failing to reach “diplomat status,” a position unofficially reserved for men, she resigned from the service in 1939. When the tensions between Germany and the rest of Europe exploded, Virginia Hall returned again to her beloved France, this time as an ambulance driver for the French 9th Artillery Regiment in 1940.

Painted by Jeff Bass, this picture shows Virginia Hall sending a message via her “suitcase radio.” It is part of the CIA’s Fine Arts collection.

That same year the Germans’ takeover of Paris, the rise of Marshal Philippe Petain, and the complicity of much of France with the Nazis, led Virginia Hall to recognize “the battle of truth against tyranny.” Leaving France and heading for Spain and later England, she connected with the newly established British Special Operations Executive there, and in April 1941, she started preparing for her first secret mission in France, modeled on the success the Irish had had against the British when the general population rose up against British rule in 1919 – 1921 and gained their independence. The SOE believed that by stirring up the French population against their oppressors in similar ways, that France, too, might throw off the yoke of the Nazis and the Petain collaborators. As an early SOE recruit, Virginia Hall’s innate creativity, dedication, and sheer bravery made this position a perfect “fit” for her during the war.

Insistent on maintaining absolute secrecy and taking no other agent for granted, she was able to slip through the traps that often nabbed other SOE agents less meticulous in their behavior. One of her most famous successes was the liberation of twelve agents, arrested by Petain’s Vichy police in October, 1941, and imprisoned at Mauzac Prison where they remained until August 1942. All previous efforts by the SOE administration had failed to secure their release and the allies feared for their safety. Using several sympathizers to help her – the wife of a prisoner, a crippled priest who smuggled a radio transmitter in under his robe, and a Corsican driver of an old Citroen truck – Virginia Hall set up a plan that required impeccable timing – “Twelve minutes, twelve men.” As author Sonia Purnell details these plans and their execution, readers will become so caught up in Purnell’s compelling narrative, and so full of admiration for her subject, Virginia Hall, that many readers will breathe a sigh of relief and whisper a quiet “thanks” to Ms. Hall for being there. Other daring rescues follow.

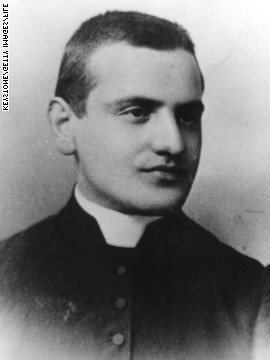

Virginia Hall receiving the Distinguished Service Cross from Gen. William “Wild Bill” Donovan. She was the only civilian woman to receive this honor.

By late 1942, having spent two years working undercover in an area of France teeming with Germans and Vichy collaborators, including five hundred new Nazi supporters assigned in the immediate aftermath of the Mauzac escape, Virginia Hall realized that her cover was blown. In a daring and dangerous escape in November, 1942, she and a guide, who was unaware that she was walking on an artificial leg, trekked over a 7500-foot pass in the Pyrenees to Spain, a distance of fifty miles, done in two days. Even when she managed, eventually, to get back to England, she negotiated a return to France and her efforts there, this time arriving through the American OSS (Operation of Strategic Service). At the end of the war, she returned to the US to work for the CIA, living quietly in her family’s former vacation house at Boxhorn Farm, Maryland, with her husband. whom she met in France. Author Sonia Purnell, who spent years researching the life and success of Virginia Hall, has written a fully annotated biography so momentous and so gripping that it is difficult to regard this book as “academic” non-fiction. A true story for the ages, it comes with extensive photographs which make it easy to imagine the life and bravery of Virginia Hall. Ultimately, however much I was grateful for Virginia Hall and her dedication to freedom during the war and after, I was equally grateful for Sonia Purnell who told an “untold story” and made it not just stimulating, but ultimately, inspiring.

Boxhorn Farm, formerly the summer house of Virginia Hall’s family, where she chose to live quietly with her spouse in the years after the war.

Photos: The photo of Virginia Hall as a young woman appears on https://www.dailymail.co.uk

The painting of Virginia Hall sending a message via her “suitcase radio” is by Jeff Bass and is part of the CIA collection of Fine Arts. https://www.smithsonianmag.com

Sonia Purnell’s photo is from https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com

Virginia Hall receiving the Distinguished Service Cross from Gen. William “Wild Bill” Donovan may be found on https://en.wikipedia.org

Boxhorn Farm, once the summer house of Virginia Hall’s family became her own residence with her husband Paul Goillot: https://craiggralley.com/

Sebastian Barry’s previous novel,

Sebastian Barry’s previous novel,

Although much-loved author Jane Austen is a dominating force throughout this biographical novel by Gill Hornby, most of the action here revolves around Jane’s older sister Cassandra.

Although much-loved author Jane Austen is a dominating force throughout this biographical novel by Gill Hornby, most of the action here revolves around Jane’s older sister Cassandra.

Micah Mortimer, the main character of Anne Tyler’s latest novel, her twenty-third, could not be more ordinary, at least on the surface, yet Anne Tyler makes his story one that will keep even jaded readers intrigued and involved in his unexciting life.

Micah Mortimer, the main character of Anne Tyler’s latest novel, her twenty-third, could not be more ordinary, at least on the surface, yet Anne Tyler makes his story one that will keep even jaded readers intrigued and involved in his unexciting life.