“How singular the fate of these poor little girls,

frail creatures offered in sacrifice

to the Parisian Minotaur,

a monster far more terrible

than the Minotaur of antiquity,

and one that devours virgins

by the hundreds each year

with no Theseus to rescue them!”

– epigraph, Theophile Gautier

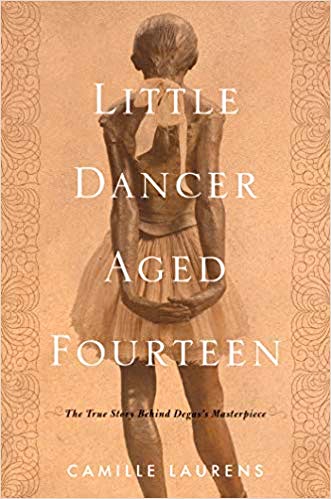

For those who have always seen Edgar Degas’s most iconic ballerina sculpture as a sweet, romantic symbol of dreams and hopes, this study of the model, the artist, and the environment in which the sculpture was created may be a shock. Author Camille Laurens spent over two years doing research on this sculpture and its model as part of her PhD. thesis, and she became totally consumed with the little dancer’s victimization. In 1880, the little girl who became the model for the sculpture, Marie van Goethem, was the fourteen-year-old child of Belgian immigrants, unschooled and working in the Paris Opera as a “little rat,” a child in training for the corps de ballet and earning almost no money. It was a horrific environment for young girls. Everyone in Paris was aware of the “pedophilia, pimping, and the corruption of minors” to which these “little rats” were subjected on a regular basis, often promoted by their avaricious mothers. Even Degas himself is quoted as saying that “The prevailing moral code was a total lack of moral code.”

Harsh reality comes alive as Marie is needed by her family to help support them, and she eventually follows in the footsteps of her older sister, accepting a modeling job with Edgar Degas. Working as an artist’s model earns her three times as much for four or five hours of work as she earns in a day at the Paris Opera, and working both jobs is tiring but financially ideal. Again, reality enters, and Marie is dismissed from the ballet for missing too many rehearsals. For at least a year, however, while Degas is working on the sculpture for which she is posing, she has better income and her family is better off. When Degas finally exhibits “Little Dancer” in 1881, it is a shock to viewers and critics. First, it is in wax, the medium normally used for first experiments and not for “finished” work. Secondly, the dancer’s clothing is real, as are her ballet slippers. And the public is astonished at her appearance: “Does there truly exist an artist’s model this horrid, this repulsive?” one critic asks. Another wonders, “Can art descend any lower?” A third refers to Marie as “a flower of the gutter.” After this showing, Degas never shows this sculpture again, and he never has it cast. The existing copies we have all seen in museums were not made until after his death in 1917, thirty-six years later.

Harsh reality comes alive as Marie is needed by her family to help support them, and she eventually follows in the footsteps of her older sister, accepting a modeling job with Edgar Degas. Working as an artist’s model earns her three times as much for four or five hours of work as she earns in a day at the Paris Opera, and working both jobs is tiring but financially ideal. Again, reality enters, and Marie is dismissed from the ballet for missing too many rehearsals. For at least a year, however, while Degas is working on the sculpture for which she is posing, she has better income and her family is better off. When Degas finally exhibits “Little Dancer” in 1881, it is a shock to viewers and critics. First, it is in wax, the medium normally used for first experiments and not for “finished” work. Secondly, the dancer’s clothing is real, as are her ballet slippers. And the public is astonished at her appearance: “Does there truly exist an artist’s model this horrid, this repulsive?” one critic asks. Another wonders, “Can art descend any lower?” A third refers to Marie as “a flower of the gutter.” After this showing, Degas never shows this sculpture again, and he never has it cast. The existing copies we have all seen in museums were not made until after his death in 1917, thirty-six years later.

Among the most fascinating aspects of the author’s depiction of Degas himself are the sociological and philosophical influences which affected him and his work, and some of this may explain why the critics and viewers were almost universally negative about the depiction of the Little Dancer in 1881. Those who have read The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal, which features insights into the Impressionists and “border-line” Impressionists like Degas, are already familiar with the rampant anti-Semitism of the Parisian art world in the 1880’s, and some may recall that Degas was depicted in that book as the most virulent anti-Semite of them all. In Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen, Degas also reveals himself to be intolerant, even hateful, of other groups who are not part his own inner circle. Though he is realistic in showing that the Little Dancer leads an exhausting and painful life, he also uses this sculpture to illustrate his own belief in phrenology, which pervaded Parisian social life at that time, and his depiction of his dancer’s face and head may be harsher than they actually looked in real life. Her sloping forehead, prominent cheekbones, and thick hair give her “a criminal look,” as do her “Aztec features,” according to the tenets of phrenology.

The author points out that in the preparatory drawings for this sculpture, Degas actually “changed her face to give it the hallmarks of a savage, quasi-Neanderthal primitivism, a precocious degeneracy. He literally altered her nature.” Ultimately, author Laurens admits that “it is hard not to loathe this forty-something conformist who in modeling his wax manipulated a very young girl for reasons that have nothing to do with art or aesthetics.” Several critics in the 1880s tried to justify Degas’s behavior in this area, claiming that he was trying to surprise viewers and make them think of how beauty can evolve from ugliness, opening the viewer’s mind to new ideas. Most viewers, however, were offended by the fact that the sculpture, presented inside a glass case, “on satin cloth as though it were an ethnographic curiosity,” was nothing more than “a doll, a common wax doll.” Ultimately, it becomes clear that no one knew then how to interpret this sculpture as sculpture, and I am not sure, after reading this fascinating book, how many readers in the present will separate Degas’s difficult, often mean-spirited personality from his sculpture, its background, and the controversies it engenders even within this book. Does it really matter to the aesthetics of the work that the Little Dancer’s physiognomy is not “accurate”? Or that the sculptor was illustrating an irrelevant phrenological agenda? Or, less likely, that he may have been trying to wake up Parisians to their false assumptions about the poor, the foreign, and uneducated?

As she completes her research and her commentary into the Little Dancer, Camille Laurens finds herself experiencing “a feeling of remorse” regarding Marie van Goethem – “I haven’t brought to [the sculpture] the genius she deserves. When it comes to her reality, I have said nothing, shown nothing…All can see her, [and] I cannot abandon her without doing more for her memory.” She believes that returning to original sources is the only way to do this. There, she finds some information regarding Marie’s family – her older sister sentenced to three months in prison, younger sister staying at the Paris Opera for her whole career. Eventually, “the shade of Marie melts into the deep shadow that Degas himself disappeared into. Her ghost is carried off, buried with his remains. Nothing can separate them any longer,” the ultimate irony. Fascinating story of an intriguing sculpture by an author who has “done her homework.”

ALSO reviewed here, by Camille Laurens: WHO YOU THINK I AM

Sacha Guitry, an actor, playwright, film maker, and friend of many artists of the day, filmed Edgar Degas walking down the street in 1915. Degas was nearly blind and is using a cane as he walks with a woman friend. He is visible at the 14 second mark, and these 14 seconds are the only film ever recorded of Edgar Degas.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.dijonbeaunemag.fr

“Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen,” a photograph from one of the castings, this one at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

The Palais Garnier, where the Paris Opera held its performances: https://www.archdaily.com/

Degas, Self-Portrait, 1895. http://www.frederickholmesandcompany.com/

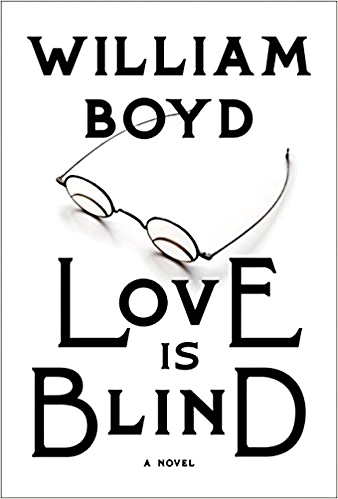

Love is Blind, British author William Boyd’s thrilling new novel, reflects the kinds of excitements, revelations, and atmosphere so common to the great Russian romances of the nineteenth century.

Love is Blind, British author William Boyd’s thrilling new novel, reflects the kinds of excitements, revelations, and atmosphere so common to the great Russian romances of the nineteenth century.