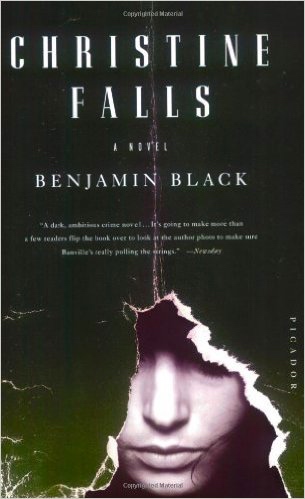

NOTE: This novel, published in 2007, is the first of a series of mystery novels written by award-winning author John Banville, under the pen name of Benjamin Black, and set in Dublin in the 1950s. Because seven of the novels in the current series all feature the same main character, Quirke, whose life gradually opens to the reader during the series, I am re-posting this review of the first Quirke novel from 2007, along with a review of the second novel in the series, The Silver Swan from 2008, which help to explain the complex background of Quirke as we see him in his new novel, the seventh Quirke novel, Even the Dead, also reviewed here.

“There’ll be a lot of dust if these particular pillars of society are brought down. A lot of dust, and bricks, and rubble. A body would want to be standing well out of the way.”

Writing this thoughtful mystery with the same care that he devotes to his “serious” fiction, Booker Prize-winning author John Banville, using the pen name of “Benjamin Black,” draws on all facets of Dublin society and its Roman Catholic heritage to investigate the question of sin in all its aspects. The result is a vibrantly alive, intensely realized story of Dublin life and values in the 1950s—a mystery which makes the reader think at the same time that s/he is being entertained. Most of the characters, like most of Ireland, hold deeply ingrained religious beliefs, revere the clergy and the institution of the church, and recognize that the church is not only a source of inspiration but a dominant force in the country’s social, as well as business and financial, life. Unlike most of the characters, Quirke, the main character, holds no awe for the church. A man in his early forties, “big and heavy and awkward,” Quirke is a pathologist/coroner at Holy Family Hospital, a man whose wife has died in childbirth, and who “prizes his loneliness as mark of some distinction.” A realist, he has seen the dark side of life too often to hold out much hope for the future, his own or anyone else’s.

Writing this thoughtful mystery with the same care that he devotes to his “serious” fiction, Booker Prize-winning author John Banville, using the pen name of “Benjamin Black,” draws on all facets of Dublin society and its Roman Catholic heritage to investigate the question of sin in all its aspects. The result is a vibrantly alive, intensely realized story of Dublin life and values in the 1950s—a mystery which makes the reader think at the same time that s/he is being entertained. Most of the characters, like most of Ireland, hold deeply ingrained religious beliefs, revere the clergy and the institution of the church, and recognize that the church is not only a source of inspiration but a dominant force in the country’s social, as well as business and financial, life. Unlike most of the characters, Quirke, the main character, holds no awe for the church. A man in his early forties, “big and heavy and awkward,” Quirke is a pathologist/coroner at Holy Family Hospital, a man whose wife has died in childbirth, and who “prizes his loneliness as mark of some distinction.” A realist, he has seen the dark side of life too often to hold out much hope for the future, his own or anyone else’s.

His vision of humanity is not improved when he goes to his office unexpectedly one evening and finds his brother-in-law, famed obstetrician Malachy Griffin, altering documents regarding the death of a young woman, Christine Falls. When Quirke performs his autopsy on the woman, he discovers, not surprisingly, that Christine Falls has died in childbirth, that the place where she was found is different from the place listed in the documents, and that the fate of her baby is unknown. Quirke’s dedication to finding out the full circumstances of Christine’s death forms the basis of the novel’s mystery, but Banville has always been a complex novelist, as interested in character as in plot, and this novel is no exception. Quirke is particularly committed to resolving the mysteries surrounding Christine’s death and the fate of her orphaned child since he knows nothing about his own parentage.

Quirke lived in an orphanage before being unofficially adopted by Judge Garrett Griffin, father of Dr. Malachy Griffin, who is obviously involved in the case of Christine Falls. Malachy and Quirke grew up together and eventually married sisters, and Quirke has deep feelings for Malachy’s wife Sarah, for her daughter Phoebe, and for Judge Griffin, his adoptive father. He is distressed at Malachy’s attempt to involve him in a cover-up. Developing on parallel planes, the novel becomes a study of Quirke and his personal relationships, at the same time that it is a study of Christine Falls and what she represents about Dublin society, the medical profession, and the church and its influence. As one might guess from her symbolic name, Christine has “fallen,” at least in the view of the church, but the nature of her sin does not begin to compare to the sins that Quirke uncovers during his investigation of her death and the fate of her child.

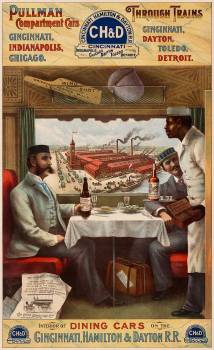

Gradually, the reader learns about the Knights of St. Patrick, a conservative Catholic organization with which Malachy and Judge Griffin are associated; the association of these Knights with certain American charities; the behind-the-scenes administration of orphanages and convents; and the nature of power in upper-echelon Dublin. Throughout, the author raises questions about the nature of good and evil and what constitutes sin. Murders, torture, beatings, and violence keep the action level high, and while this action is sometimes a bit melodramatic, with convenient coincidences, it is in keeping with the great, old-fashioned tradition of 1950s mystery-writing. A change of location from Dublin to Boston adds to the flavor and broadens the scope of Quirke’s investigation, connecting the mystery to the history of the Irish and their traditions in Boston.

As always, Banville is a consummate artist, dedicating as much attention and care to his descriptions in this mystery as he does in his “literary” novels. The introduction, sure to arouse interest in any reader, emphasizes a young woman’s response when she is handed a baby to take on a journey—”What struck [her] first about the bundle was the heat: it might have been a lump of burning coal that was wrapped in the blanket, except that it was soft, and that it moved…” He uses parallel scenes to show contrasts and similarities (a Christmas party in Dublin vs. a Christmas party in Boston, both of which end violently), and shows his mastery of voice as he maintains a conversational tone appropriate for Quirke. One hopes that Banville will continue the story of Quirke, a character with enormous potential for further development. After this fine debut mystery, one can easily imagine Banville becoming, like Graham Greene, a writer of both serious literary fiction and “entertainments.”

ALSO by Benjamin Black: THE SILVER SWAN (Quirke), THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE (Raymond Chandler), A DEATH IN SUMMER (Quirke), VENGEANCE (Quirke), EVEN THE DEAD (Quirke)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears in http://www.independent.ie/

A hospital autopsy room like this one from the 1950s would have been familiar to main character Quirke. https://www.pinterest.com/sarlou56/hospital-history/

The poster from the Quirke TV mini-series is from http://www.imdb.com/

Although this is an oldie from 2004, it remains one of the wildest Christmas stories ever created, popular for its wacky humor, its crazy satire of Christmas excesses, and its never-ending ride through what feels like an alternative universe, all part of the style which author Christopher Moore has perfected over the years. In the case of The Stupidest Angel, the setting is familiar for those who have read Moore’s previous books, since Moore is reprising many of the most popular characters from the past in this Christmas-inspired caricature of life in Pine Cove, a California coastal community, filled with “holiday quaintage” and “festive doom.”

Although this is an oldie from 2004, it remains one of the wildest Christmas stories ever created, popular for its wacky humor, its crazy satire of Christmas excesses, and its never-ending ride through what feels like an alternative universe, all part of the style which author Christopher Moore has perfected over the years. In the case of The Stupidest Angel, the setting is familiar for those who have read Moore’s previous books, since Moore is reprising many of the most popular characters from the past in this Christmas-inspired caricature of life in Pine Cove, a California coastal community, filled with “holiday quaintage” and “festive doom.”

Lena’s fight with Dale was, unfortunately, witnessed by young Josh Barker, age seven, who is now distraught at the thought that “someone killed Santa.” Soon little Josh is visited by the Archangel Raziel, who appeared in Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, a klutzy angel whose mission it is to “Go to Earth, find a child who has made a Christmas wish that can only be granted by divine intervention,” and do something for him. Josh wants Santa to come back to life.

Lena’s fight with Dale was, unfortunately, witnessed by young Josh Barker, age seven, who is now distraught at the thought that “someone killed Santa.” Soon little Josh is visited by the Archangel Raziel, who appeared in Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, a klutzy angel whose mission it is to “Go to Earth, find a child who has made a Christmas wish that can only be granted by divine intervention,” and do something for him. Josh wants Santa to come back to life.