“We were at the supermarket, shopping for the weekend. At some point she said, you go stand in the cheese line while I get the rest of the groceries. When I came back, the shopping cart was half filled…What kind of cheese did you buy? –A Crottin de Chavignol and a Morbier. –And no Gruyere? she cried out…Who wants to eat Morbier? Who likes this Morbier crap? –I do, I said.” Things went downhill from there. –Robert Toscano

In the opening salvo of this darkly humorous but deeply sensitive collection of interconnected vignettes, French author Yasmina Reza sets the scene for her exploration of love and marriage, family and home, romantic satisfaction and dysfunction in modern France. The often huge gap between what people, including the reader, see from the outside and what the characters are really thinking creates opportunities for great irony and delightfully witty exchanges as the author, also a successful dramatist, reveals her characters through small, everyday details and animated conversations. Each of the twenty vignettes is limited to six or seven pages, and the author’s smart and rapid-fire presentations lead to each vignette having its own punch line and thematic development. The pure delight of reading Reza’s wonderfully controlled and lively prose (artfully translated by John Cullen), grows as the reader discovers that the characters in one sketch often appear in other sketches, too, leading to a broad picture of several families, their friends, and their lovers, as seen from several different points of view. Robert Toscano, whom we meet in the opening scene, and his wife Odile, for example, each have two separate vignettes, and reappear in each other’s lives, while Odile’s family – her father, mother, and aunt – also have their own points of view which broaden the focus. Ultimately, each sketch becomes an integral part of the overall depiction of time, place, and character, and this collection begins to resemble a novel.

In the opening salvo of this darkly humorous but deeply sensitive collection of interconnected vignettes, French author Yasmina Reza sets the scene for her exploration of love and marriage, family and home, romantic satisfaction and dysfunction in modern France. The often huge gap between what people, including the reader, see from the outside and what the characters are really thinking creates opportunities for great irony and delightfully witty exchanges as the author, also a successful dramatist, reveals her characters through small, everyday details and animated conversations. Each of the twenty vignettes is limited to six or seven pages, and the author’s smart and rapid-fire presentations lead to each vignette having its own punch line and thematic development. The pure delight of reading Reza’s wonderfully controlled and lively prose (artfully translated by John Cullen), grows as the reader discovers that the characters in one sketch often appear in other sketches, too, leading to a broad picture of several families, their friends, and their lovers, as seen from several different points of view. Robert Toscano, whom we meet in the opening scene, and his wife Odile, for example, each have two separate vignettes, and reappear in each other’s lives, while Odile’s family – her father, mother, and aunt – also have their own points of view which broaden the focus. Ultimately, each sketch becomes an integral part of the overall depiction of time, place, and character, and this collection begins to resemble a novel.

In the opening vignette, the psychological warfare between Robert Toscano and Odile, his wife, over his failure to buy the Gruyere cheese that she likes, contrasts with the next sketch. In that one, Odile’s aunt Marguerite, a lonely woman whose husband and children are gone, wants only to meet “some lighthearted person” with whom she can laugh, someone who also likes to walk. The theme of personal isolation, even when surrounded by others, pervades the book on all levels, and the ways in which the characters attempt to connect with each other or deal with their loneliness privately, engage the reader because they feel ordinary and familiar. Reza is a master at including small details to emphasize her ideas: After the big argument about cheese between Robert and Odile at the market, their young son Antoine awakens at night, crying because his stuffed toy “Doudine” is lost in his bed, thereby adding to the picture we get of the need for connection and the loneliness when it is missing, as Odile and Robert prove when they finally turn out the lights.

Robert Toscano chose Morbier cheese, while his wife Odile wanted Gruyere, leading to a public spat in the market.

The Toscanos consider the Hutners to be their friends, though privately Robert mocks them for referring to each other as “my own” and because the wife, Pascaline, has worked so hard to make a “turbot en croute” just for her husband and herself. The Hutners’ seemingly idyllic relationship, which we see from the Toscanos’ point of view, is shattered for the reader when Pascaline indicates in her vignette that their son, whom everyone believes is away studying, is suffering from severe mental illness. The psychiatrist who is treating him, Dr. Igor Lorrain, also appears several times here, in the sketches for Paola Suares, Chantal Audouin, and Helen Barneche, who knew him many years ago. Among the other overlaps: Robert’s friend Luc Condamine, who works with him, is trying to set him up with Virginie, a medical secretary, who has her own touching story. Odile, Robert’s wife, is having an affair with another character here, someone she believes will save her “from Robert, from time, and from melancholy.” New lovers and former lovers serve as contrasts to present romantic attachments and separations.

Virginie Deruelle visits her great-aunt at a home for the elderly where Piaf sings and the residents crochet patchwork throws which no one uses.

Just as Reza incorporates many different forms of love, she also includes many different approaches to the future, with death often lurking in the background. When one character falls ill, his daughter calls her mother while the mother is out happily relearning how to drive, after thirty years, and shopping for a new dress which she does not want and does not think she needs. In classically dark humor, the daughter gives her mother the news, saying that her father will need an angiogram, and then asks, “Did you try on that dress at Franck et Fils, Maman?” The man’s eventual death and his stated desire to be cremated lead to many reminiscences among the characters who know each other and are there to support each other. Neighbors and friends appear and eulogies are given. The man’s wife notes that she is not even mentioned in his obituary, however, and the trip to the small town where the man grew up and where they lived in the early days of their marriage, becomes a pilgrimage for the family as they depart to sprinkle his ashes where his father’s ashes were sprinkled. Much has changed in that town, just as life has changed constantly in the course of the lives the author has illustrated here.

I have concentrated here on a just few of the book’s main characters in an effort to convey the spirit and some of the ideas within this entire marvelous collection, which, in terms of its overlapping characters often feels like a novel. Filled with ironies, the book is great fun to read and is often funny, even as the author also depicts the loneliness of others and the genuine sadness of their lives. Ultimately, the reader comes back to the quotation with which the author introduces the book:

Happy are those who are beloved

and those who love

and those who can do without love.

Happy are the happy. –Jorge Luis Borges

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Spilett appears on http://www.babelio.com

The Morbier cheese is found on http://www.oldeuropecheese.com/

The crocheted patchwork throw is from https://www.etsy.com/

The crematorium at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery appears on http://www.panoramio.com Photo by Mickael Do Rego

ARC: Other Press

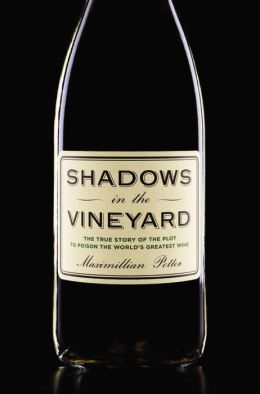

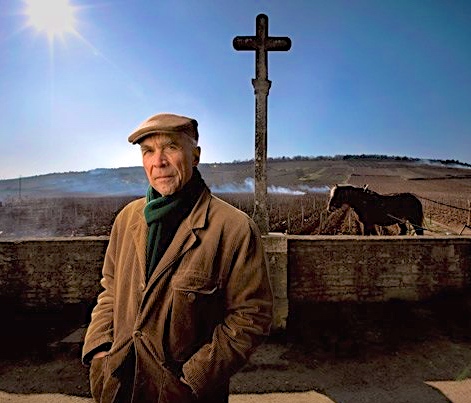

The language with which vintners, connoisseurs, and critics talk about their favorite subject often resembles religious ecstasies, making the use of sacred wine for Christian communion services seem not only appropriate but completely right. Fortunately for readers of this book, which is “the true story of the plot to poison the world’s greatest wine,” author Maximillian Potter, a journalist, takes a more secular approach to this subject, as he investigates the very real 2010 plot to poison the vines at the Domaine Romanee-Conti on the Cote d’Or, which has been in the same family for almost three hundred years. With its Pinot Noir regarded as the world’s greatest wine, and its availability extremely limited because the vineyard itself is small, the interest of sophisticated criminals in this wine is not surprising. “Bottle for bottle, vintage for vintage, Romanee-Conti is the most coveted, rarest, and thereby the most expensive wine on the planet. At auction, a single bottle of Romanee-Conti from 1945 was then fetching as much as $124,000.”

The language with which vintners, connoisseurs, and critics talk about their favorite subject often resembles religious ecstasies, making the use of sacred wine for Christian communion services seem not only appropriate but completely right. Fortunately for readers of this book, which is “the true story of the plot to poison the world’s greatest wine,” author Maximillian Potter, a journalist, takes a more secular approach to this subject, as he investigates the very real 2010 plot to poison the vines at the Domaine Romanee-Conti on the Cote d’Or, which has been in the same family for almost three hundred years. With its Pinot Noir regarded as the world’s greatest wine, and its availability extremely limited because the vineyard itself is small, the interest of sophisticated criminals in this wine is not surprising. “Bottle for bottle, vintage for vintage, Romanee-Conti is the most coveted, rarest, and thereby the most expensive wine on the planet. At auction, a single bottle of Romanee-Conti from 1945 was then fetching as much as $124,000.”

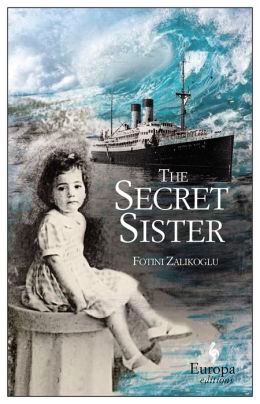

Greek author Fotini Tsalikoglou, in her first novel to be translated into English, introduces a man we come to know as Jonathan, along with the first of his family’s many mysteries. Jonathan has just boarded a plane from New York City to Athens, and while sitting next to an empty seat in the plane, he speaks to it as if it were “Amalia,” his sister. He is remembering an unnamed woman who dragged him, as a small child, to museums all over New York to see Greek statues and pediments, but who never had any interest in going to Greece herself. He is puzzled because, despite this behavior toward Greek art, she was clearly “revolted by her country.” Her name was Lale Andersen, a name she chose when she changed it from the original, and she was Jonathan’s “mutant mother.”

Greek author Fotini Tsalikoglou, in her first novel to be translated into English, introduces a man we come to know as Jonathan, along with the first of his family’s many mysteries. Jonathan has just boarded a plane from New York City to Athens, and while sitting next to an empty seat in the plane, he speaks to it as if it were “Amalia,” his sister. He is remembering an unnamed woman who dragged him, as a small child, to museums all over New York to see Greek statues and pediments, but who never had any interest in going to Greece herself. He is puzzled because, despite this behavior toward Greek art, she was clearly “revolted by her country.” Her name was Lale Andersen, a name she chose when she changed it from the original, and she was Jonathan’s “mutant mother.”