“Often she danced alone, and she forced the [band] to quicken their pace, or they couldn’t keep time to the flurry of her hips. Oona was their enchantress, and she came out onto the floor with Sonny Salinger, expecting to teach him a few tricks. But he seized her with alacrity, and she spun around him like a spindle on a silken thread.” – Oona at the Stork Club, 1942.

With a first chapter set at the Stork Club, where Oona O’Neill, then a sixteen-year-old “voluptuous child,” sits at Walter Winchell’s Table 50, author Jerome Charyn creates a mood of wild nights and war-fueled abandon in New York shortly after the recent Pearl Harbor attack. Oona, young daughter of Nobel-Prize-winning playwright Eugene O’Neill, has her own closet at the Stork, “where she [can] park her Mary Janes and put on strapless dresses” which she buys at a discount house because she can not afford Saks. This night she is waiting excitedly for one of her beaux, Sonny Salinger, a short story writer, and when he arrives at the Stork, he joins Oona and Winchell at Table 50. Winchell introduces Sonny to Ernest Hemingway, one of Sonny’s idols, a few tables behind them. Hemingway, a civilian, anxious to become a colonel with his own battalion, is there hoping that Winchell’s close connections with FDR will help him, but Hemingway and Winchell do not get along, and both are on edge that night, bickering at each other. Salinger himself has always despised the Stork Club and all its glitter, but he is head over heels in love with Oona, and when the tension grows ominously between Winchell and Hemingway, Salinger and Oona go to another room, dance the rhumba, and then leave the premises. That night, when Salinger arrives at home, he finds an Order of Induction from the President of the United States. Drafted to work in Counter Intelligence, he must leave for Fort Dix immediately.

With a first chapter set at the Stork Club, where Oona O’Neill, then a sixteen-year-old “voluptuous child,” sits at Walter Winchell’s Table 50, author Jerome Charyn creates a mood of wild nights and war-fueled abandon in New York shortly after the recent Pearl Harbor attack. Oona, young daughter of Nobel-Prize-winning playwright Eugene O’Neill, has her own closet at the Stork, “where she [can] park her Mary Janes and put on strapless dresses” which she buys at a discount house because she can not afford Saks. This night she is waiting excitedly for one of her beaux, Sonny Salinger, a short story writer, and when he arrives at the Stork, he joins Oona and Winchell at Table 50. Winchell introduces Sonny to Ernest Hemingway, one of Sonny’s idols, a few tables behind them. Hemingway, a civilian, anxious to become a colonel with his own battalion, is there hoping that Winchell’s close connections with FDR will help him, but Hemingway and Winchell do not get along, and both are on edge that night, bickering at each other. Salinger himself has always despised the Stork Club and all its glitter, but he is head over heels in love with Oona, and when the tension grows ominously between Winchell and Hemingway, Salinger and Oona go to another room, dance the rhumba, and then leave the premises. That night, when Salinger arrives at home, he finds an Order of Induction from the President of the United States. Drafted to work in Counter Intelligence, he must leave for Fort Dix immediately.

Those whose familiarity with the life of J. D. Salinger focuses primarily on his hermit-like existence later in life, will find his early activities from 1942 – 1946, detailed in the opening chapters at the Stork and in the crises he faces throughout the war, especially revealing of his life and personality. Author Jerome Charyn is particularly careful to connect the events in ways which allow the reader to feel the traumas and horrors. In an early episode set in Slapton Sands in England, Salinger is dramatically affected when he receives an unexpected phone call from Oona, now married, a personal call on a public phone which infuriates his superior officer. Since Slapton Sands is an area being used to practice for a landing at Normandy, tensions are very high. At this point, his superior officer assigns Salinger to evaluate whether some sketches drawn by people he knows might have been reconnaissance destined for the enemy, an interrogation which requires him to be brutal. He “agrees” to give the two soldiers “another licking,” but does not do so once his superior leaves. Instead, he impounds the sketchbooks. A disastrous attack on the unit leads Salinger to retreat into himself for many hours, and suggests that he has been more emotionally injured than what is, at first, obvious.

Salinger later arrives in Normandy, where he discovers, after a battle, that a captain he knows has “lost it,” and learns the true meaning of the “Screaming Meemies.” Determined not to leave his emotionally shattered captain behind, he drags him toward safety through a flooded farmland and booby-trapped town, in which even the pretzels are poisoned. In Cherbourg they must capture the port in order to keep their tanks and trucks supplied with gasoline, and Salinger is in charge of questioning a young boy who belongs to the milice, a boy who has executed the former mayor. A “priest” who wants to serve them a meal is also questioned, and turned over to an internment camp. Eventually, a fire, encouraged by a superior, breaks out in a hotel in which some rebels are hiding, and the major takes over, prohibiting Salinger from getting involved. The horrors continue until the Allies suddenly sweep across France, and Ike and his generals prepare to deal with Paris, just as Salinger’s unit, the Twelfth, gets ready to enter the city.

For Salinger, virtually everything is affecting, and he is soon in charge of dealing with civilian Ernest Hemingway in Paris. Hemingway, as he indicated at the Stork, ages ago, has succeeded in collecting a “band of stragglers around him…a motley crew of soldiers, civilians, and Resistance fighters equipped with submachine guns and hand grenades.” Salinger is assigned to “bring [the captain] Hemingway’s scalp,” and he is surprised when he finds that Hemingway has “ballooned out” in the time since he last saw him. When told that he has to give up his weapons to keep him from complicating the generals’ plans, Hemingway finds himself boxed into the Ritz and decides to lie low there. Salinger moves on to Luxembourg and eventually to a small Bavarian village which reveals the unspeakable horrors of the SS elite against everyone who got in their way, including gypsies, Serbs, Jews, half Jews, and very young children, one of whom with permanent injuries he rescues and relocates in safety. He is so torn by what he has seen in the course of the war, however, that he begins to become suicidal and actively seeks mental help.

Author Jerome Charyn uses Salinger’s remaining time in Europe to develop an ending in sharp contrast to the beginning. Instead of sweet Oona, Salinger becomes involved with a German woman, suspected of having been a member of the Gestapo. In this relationship, “there were no boundaries between peace and war….They’d battle until he was all black-and-blue,” with Salinger wearing his holster while making love. Their distorted relationship resembles Salinger’s relationships with the army and the war itself, and after he and Sylvia end their relationship, he continues to spend most of his time inside his head reliving his memories and their unending horrors. Readers who admire Salinger’s writing will find this fictional biography of his life when he was in his twenties both enlightening and heartbreaking, as he struggles with his concept of who he is – and why. Publishing two short stories after the war, Salinger begins to see some light, and five years after his return home from Europe, he publishes his most famous book, Catcher in the Rye. How much of a recovery that represents is left up to the reader.

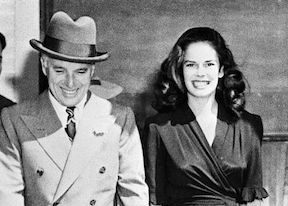

In 1943, Oona O’Neill married Charlie Chaplin the day after her 18th birthday. He was 36 years older, and the marriage lasted 34 years, until his death. They had eight children.

Photos. Happy Oona O’Neill and J. D. Salinger, 1942, are found here: https://www.razon.com.mx

Salinger in 1944. https://www.quora.com

Photographer Robert Capa, a driver, and Ernest Hemingway, near the end of World War II. www.vanityfair.com

Author Jerome Charyn: https://www.vanityfair.com Photo by Klaus Schoenwiese.

Oona O’Neill, married in 1943, the day after her 18th birthday, to Charlie Chaplin, 36 years older. The marriage lasted 34 years until his death at age 88 and produced eight children. https://www.countryliving.com

Few authors convey the inner thoughts of characters with the insight and sensitivity of Hungarian author Magda Szabo, and this novel may be one of her most insightful.

Few authors convey the inner thoughts of characters with the insight and sensitivity of Hungarian author Magda Szabo, and this novel may be one of her most insightful.

It is no secret that Italian author Paolo Maurensig loves chess.

It is no secret that Italian author Paolo Maurensig loves chess.

Note: Each year I enjoy looking at the statistics for this website to see which reviews here have garnered the most interest.

Note: Each year I enjoy looking at the statistics for this website to see which reviews here have garnered the most interest. 1 Favel Parrett—

1 Favel Parrett—  5. Irmgard Keun–

5. Irmgard Keun–