Note: Maurizio de Giovanni has been WINNER of many prizes, including the Scerbanenco Prize in Italy.

“Il Paradiso, what supreme irony. A place inhabited by the passions of hell, but named after Eden. Perhaps, though, [Ricciardi] reckoned, it was accurate. Maybe heaven and hell exist for that reason, so that they can switch places and pretend to be the perfect place for everyone.”

Maurizio de Giovanni’s sixth entry in his series of Neapolitan mysteries starring Commissario Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi will delight fans of the series and, I suspect, send new readers thronging to bookstores to get some of his earlier novels. Set in 1932, during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, this novel shows Mussolini as he consolidates his power and imposes his fascism more broadly. Many among the police, such as Angelo Garzo, the Vice Questore of Ricciardi’s department, are sympathizers and supporters who know that being on the “right side” of Il Duce will enable them to progress quickly in their careers. Inspector Ricciardi, a baron, is independently wealthy and socially well connected, however, and he feels secure enough in his position that he does not bow to the Blackshirts or act out of fear when he believes that police cover-ups are under way. Still, he is an unusual protagonist, painfully shy with women, often taciturn, and a loner, a person who has an unusual talent (or curse): If he arrives at the scene of a murder and tries to communicate with the victim, he can hear the victim speaking his last thoughts. Usually, these are puzzles in themselves, providing few clues about the murder, and Ricciardi never shares what he learns from the victims.

Maurizio de Giovanni’s sixth entry in his series of Neapolitan mysteries starring Commissario Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi will delight fans of the series and, I suspect, send new readers thronging to bookstores to get some of his earlier novels. Set in 1932, during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, this novel shows Mussolini as he consolidates his power and imposes his fascism more broadly. Many among the police, such as Angelo Garzo, the Vice Questore of Ricciardi’s department, are sympathizers and supporters who know that being on the “right side” of Il Duce will enable them to progress quickly in their careers. Inspector Ricciardi, a baron, is independently wealthy and socially well connected, however, and he feels secure enough in his position that he does not bow to the Blackshirts or act out of fear when he believes that police cover-ups are under way. Still, he is an unusual protagonist, painfully shy with women, often taciturn, and a loner, a person who has an unusual talent (or curse): If he arrives at the scene of a murder and tries to communicate with the victim, he can hear the victim speaking his last thoughts. Usually, these are puzzles in themselves, providing few clues about the murder, and Ricciardi never shares what he learns from the victims.

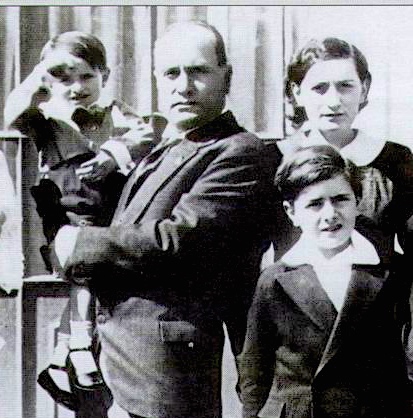

Ricciardi’s only friend, Brigadier Raffaele Maione, dotes on his many children and adores his wife. Almost a generation older than Ricciardi, Maione is supportive but respectful, never stepping out of his place to offer comment on Ricciardi’s personal life. And that personal life is a frustrating mess for long-time fans of this series. “Terrified of love because he saw its fatal effects every day,” Ricciardi, throughout the series, has been worshipping from afar a young woman, Enrica Columbo, who lives across the alley from his apartment, where he lives with his elderly tata Rosa, who raised him after he was orphaned as a child. Now frail and ailing, tata Rosa worries about his future after she is gone, and she has been nurturing the hopes of Enrica, as shy as Ricciardi, hoping that they will get beyond the smiles and subtle waves from their windows and the polite “hellos” on the stairs. Tata Rosa wastes no time on the subject of Livia Vezzi, the widow of Italy’s greatest tenor, killed at the San Carlo Opera House (in I Will Have Vengeance), Ricciardi’s first investigation. Livia, with connections to the highest levels of society, including Il Duce’s daughter Edda Mussolini, has returned to Naples to live and, she hopes, to capture the heart of Commissario Ricciardi.

The action begins when Viper, the most beautiful prostitute at Il Paradiso, a bordello, is murdered on the job. As her professional time was almost completely occupied with only two clients who have alibis – a wealthy man who specializes in the sale of religious statuettes and trinkets and a young man from her hometown who wants to marry her – the investigation soon widens to the whole of Naples. Many conferences take place between Ricciardi and Maione at Caffe Gambrinus, Ricciardi’s favorite restaurant, where Maione is asked by Ricciardi to consult with one of his “adoptees” from the fringes of life to see if s/he has any information. Bambinella, a transvestite with an active social life, sometimes sees and hears things that others are not privy to, and she trusts Maione because he not only respects her but is able to joke with her. Their delightful scenes reflect their odd friendship.

Dr. Bruno Modo, another regular, a loud man who says and does exactly what he wants, investigates and performs the autopsy. He is accompanied on all his wanderings in Naples by a little brown and white dog, which he unofficially adopted following the murder of the orphan child in The Day of the Dead. Dr. Modo, a client of Il Paradiso, is careless with his words one too many times during this investigation and finds himself in serious trouble here. The investigation takes Ricciardi out to the rural areas as he investigates some of the clients of the bordello, and these trips expand the scope of the novel as the author describes rural life and its problems during the economic downturn. Finally, an event occurs in which it is crucial for Ricciardi to get some help from the fascisti at the highest levels, and Livia Vezzi, whom Ricciardi has avoided for six months, is the only one who can help – if she will see him.

The Pastiera, the legendary ricotta cheese pie for Easter, was a joint project between Tata Rosa and Enrica.

Because the murder takes place in the week leading up to Easter, the author has great fun balancing the investigation into the low life against all the elaborate plans and home cooking being done for Easter by Lucia, Maione’s wife, and by Tata Rosa, who is teaching the shy Enrica from across the alley how to cook her holiday specialties, just in case… (De Giovanni takes great delight in describing in the most luscious detail all the specialties of the holiday, from the clam and mussel-loaded Zuppa marinara appetizer to the elaborate Pastiera, the ricotta cheese pie which is everyone’s favorite dessert, and I suspect every reader will be wishing s/he could be there for the feast.) The contrasts between the extremely poor and the very wealthy make the holiday descriptions particularly poignant, however, and bring back memories of the starving orphans from The Day of the Dead, the poor, and the homeless at a time of extreme economic difficulty. The author’s vibrant descriptive powers are at their peak in this novel which brings Naples appetizingly alive.

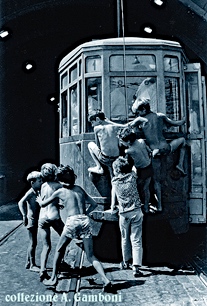

The scugnizzi, wild street children, are described as “dangling like bunches of raggedy grapes from the ends of trolley cars rattling up Via Medina.”

De Giovanni’s novels have become increasingly sophisticated and complex in their structure in the course of this series. Here, for example, he intersperses six mini-chapters of monologues by unknown speakers to provide unique points of view on the murder of Viper, and these provide clues which actually add to the mystery, since the identities of these speakers do not become clear till one re-reads them at the conclusion of the novel. At the same time, his comfort with his odd group of characters, his relaxed narrative tone, and his sometimes humorous details provide a teasing narrative which will keep readers smiling and guessing throughout. Readers new to de Giovanni will find that they gain most of the background they need through the narrative, though long-time readers will enjoy this even more. Everyone will agree, I suspect, that this is de Giovanni’s best novel yet – great fun!

ALSO by Giovanni: I WILL HAVE VENGEANCE (#1), BLOOD CURSE (#2), EVERYONE IN THEIR PLACE (#3), THE DAY OF THE DEAD (#4), BY MY HAND (#5) VIPER (#6), THE BOTTOM OF YOUR HEART (#7) GLASS SOULS: MOTHS FOR COMMISSARIO RICCIARDI (#8), NAMELESS SERENADE (#9),

Inspector Lojacono series: THE CROCODILE, THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#2), DARKNESS FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#3), COLD FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#4), PUPPIES (#5)

Photos, in order: The author’s photos is from http://inonda.tv/

Caffe Gambrinus at Piazza Trieste e Trento is where Riccardi often has meals and meetings. http://encyclopediatraveler.blogspot.com

Il Duce with three of his six children. Edda, a friend of Livia Vezzi, is in the back right: http://www.theamericanmag.com

The Pastiera, the famous Neapolitan dessert for Easter, features ricotta cheese and candied fruits. Tata Rosa encouraged Enrica to learn to make it for Ricciardi’s Easter. http://grantouritaly.blogspot.com/pastiera.html

The scugnizzi, wild street children, are described here as “dangling like bunches of raggedy grapes from the ends of trolley cars rattling up the Via Medina.” http://www.clamfer.it/

The Zuppa marinara, made with clams of various sizes and mussels and served as the appetizer for Easter, is shown here: http://www.arturostavern.com/

ARC: Europa Editions