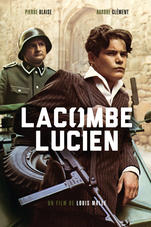

NOTE: The film of this 1974 screenplay was WINNER of the Golden Globe Best Foreign Film Award, 1975; WINNER of the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Best Film Award, 1975; and WINNER of the British Academy of Film and Television Award for Best Foreign Film, 1975.

“Personally, I don’t give a damn who wins the war, the English or the Germans!…All I know is that I’m wasting my time here….And what about my career?…Do you ever give my career a second’s thought?” — Betty, an actress, in the final days of World War II.

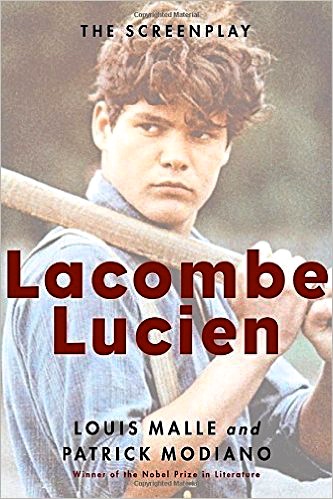

Produced and directed by famed cinematographer Louis Malle and written by Louis Malle and Patrick Modiano, who became the Nobel Prize for Literature winner in 2014, this 1974 film of Lacombe, Lucien broke some unspoken taboos when it was first shown. Only once before had a film raised questions about the masses of French citizens, many of them living in the countryside, who were ignorant or oblivious to the horrors of the Holocaust and the terrible costs to France at the hands of the Nazis in Vichy France. Marcel Ophuls had first produced a documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, in 1972, nearly thirty years after World War II ended, claiming that the prevailing view of the actions of the French citizenry during the war was naïve. Many citizens had been working farms in rural areas during the war and did not know or care to find out about what was happening on a national level – they had enough to worry about keeping food on the table and their families safe. A surprising number of citizens had collaborated with the Germans, not for political reasons, but because they believed that it was the only way they would be able to survive, and far fewer had worked with the Resistance to overthrow their German occupiers than was once believed. Ophuls suggested that most citizens just accepted what was happening because they did not believe they had much choice.

Produced and directed by famed cinematographer Louis Malle and written by Louis Malle and Patrick Modiano, who became the Nobel Prize for Literature winner in 2014, this 1974 film of Lacombe, Lucien broke some unspoken taboos when it was first shown. Only once before had a film raised questions about the masses of French citizens, many of them living in the countryside, who were ignorant or oblivious to the horrors of the Holocaust and the terrible costs to France at the hands of the Nazis in Vichy France. Marcel Ophuls had first produced a documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, in 1972, nearly thirty years after World War II ended, claiming that the prevailing view of the actions of the French citizenry during the war was naïve. Many citizens had been working farms in rural areas during the war and did not know or care to find out about what was happening on a national level – they had enough to worry about keeping food on the table and their families safe. A surprising number of citizens had collaborated with the Germans, not for political reasons, but because they believed that it was the only way they would be able to survive, and far fewer had worked with the Resistance to overthrow their German occupiers than was once believed. Ophuls suggested that most citizens just accepted what was happening because they did not believe they had much choice.

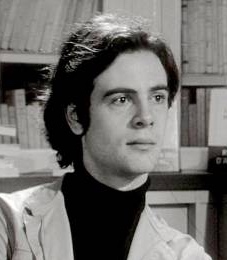

With Lacombe, Lucien, Malle and Modiano continue this theme, and both had had experiences that made this subject important to them. Malle himself was a teenager during the war, and Modiano, born in 1945, was the son of a Jew who had worked as a collaborator and blackmarketeer bringing supplies directly to the Gestapo, a humiliation which pervades much of Modiano’s writing, even to the present. As he illustrates in several of his own novels, the worst aspect of this betrayal is that his father did this purely for the money, not out of patriotism or necessity. Here Malle and Modiano become partners for the screenplay, with Malle using his background as a director and producer to bring the film into being, and Modiano helping with the dialogue and the action scenes to make them come alive. Modiano, at twenty-nine, had already written three successful novels and was no novice when it came to dialogue.

Patrick Modiano, age 29 at the time of this screenplay, and already the successful author of three novels.

The novel opens in 1944, with a boy of seventeen scrubbing the floor of a nursing home, emptying chamber pots, and cleaning rooms. When he sees a robin singing on a branch outside a hospital room, he casually takes out his slingshot and with careful aim, hits the bird, watching impassively as it falls dead to the courtyard below. Then he simply returns to his work, the bird’s death a mere interlude in an otherwise boring day. At week’s end, he takes his bicycle home to the busy farm where his family has always lived in Souleillac, only to find a family of seven eating breakfast there, his mother still in her nightgown inside, and the owner of the farm, who is her lover, still in his shirtsleeves. After threatening the new family with a shotgun, saying that if they do any damage, they’ll have to answer to him, this “tough” teenager learns that that family is living there to help with the farmwork, his father is a prisoner of war, and his brother has just joined the underground.

Lucien leaves the city for home by bicycle on the weekend, riding through farmland, almost uninhabited except by farm animals.

Wanting to be part of the action, Lucien decides to join the underground, led by one of his former teachers, Peyssac, but Peyssac tells him he is still too young. Unable to wait, Lucien goes to town, where he is caught spying on a party at a local hotel, one of the participants being Betty, the actress whose quotation begins this review. Invited inside, he cannot help boasting about the Resistance and its members, whom he knows. He wants to be part of a group, and he is so unthinking that it does not matter if it is the Resistance or the Gestapo. After drinking too much, he falls asleep, awakening the next day among a group of German sympathizers and low level soldiers, just as Peyssac is brought into the room, handcuffed. Peyssac’s screams are heard later as he is tortured. Lucien is unmoved.

A very young man who wants to be noticed, with no alliances or intellectual curiosity, Lucien is impressed by power and glory. He loves being able to carry a machine gun, being paid for his information, and the attention he gains as a “tough” Gestapo agent, albeit one who has little understanding of what his actions mean. When he ends up living in a room of a house owned by a wealthy Jewish tailor, he falls in love with the man’s daughter, and she with him. Despite her intelligence, she is apparently attracted by his raw sexual attractiveness and the possibility that he may be able to help her and her family escape from France. When the opportunity arises, Lucien acts, not out of altruistic motives or desire to help the family because they are Jewish but because it helps him get what he wants, a beautiful companion and a family which needs him. The conclusion will surprise no one.

The screenplay is short, and unlike a book that becomes a film, for which much of the book has to be omitted for lack of time, this filmscript is so short that it is possible to read the entire script in less time than the two hours it takes to see the film. For those who have never read a filmscript, and I am one, I was startled by the amount of imagination it took to figure out what the point was for many of the early scenes; how the reader was supposed to interpret the actions of Lucien, the main character; and why the conclusion was a text overwriting a scene of Lucien and his lady-love, France. Obviously, Malle and Modiano agreed ahead of time on what they wanted in the script and what they would do with it visually. For the reader, however, the filmscript, with its young and naïve main character, for whom one develops no positive feelings at all, is like reading an outline for which the director will later add information during filming. I am now anxious to see the film, which will be a far richer experience than the screenplay.

ALSO by Modiano: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, FAMILY RECORD, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE, PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

Photos, in order: The photo of Louis Malle appears on https://cinemastudies.sas.upenn.edu

The young Patrick Modiano, age twenty-nine and already the successful author of three novels, is found on https://vaguevisages.com/

Lucien rides his bicycle from the city home to the countryside on the weekend and discovers many changes in place: http://paristexasyeu.blogspot.com/

Lucien and France, in love, enjoy some quiet time in a remote area. http://www.sunrise54.fr

US film poster for this film: https://www.movieposter.com/poster/A70-3968/Lacombe_Lucien.html

ARC: Other Press