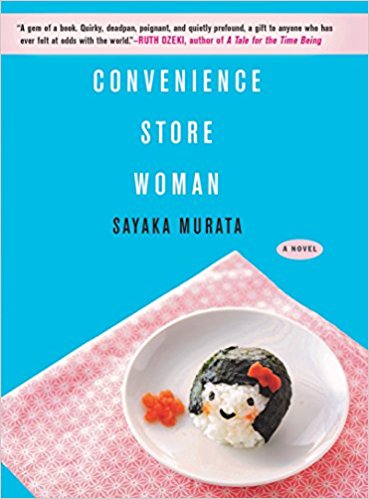

Note: This novel was WINNER of Japan’s Akutagawa Prize in 2016.

“In a short-staffed convenience store, a store worker can sometimes be highly appreciated just by existing, by virtue of not rocking the boat. I’m not particularly brilliant compared to Mrs. Izumi and Sugawara, but I’m second to none in terms of never being late or taking days off. I just come in every day without fail and because of that I’m accepted as a well-functioning part of the store.”—Keiko Furukura

Keiko Furukura has been working at her local Smile Mart convenience store for half her life, for the eighteen years since she finished high school, and she is completely comfortable in her job and in her ability to manage her life. Though she works only part-time because she says she is “not strong,” she knows where everything belongs in the store, how to restock shelves and supplies, how to update displays, and how to avoid conflict with her co-workers and customers. She likes her job, they like her, she never gets angry, and she is as happy as she can be in her role – one which that she regards as “not suitable for men.” It is the other women in her life who eventually begin to question her role at the store and her future there. She is, after all, a woman in her mid-thirties, approaching the age at which she may soon be “unable” to marry and have children, goals her family and friends have already achieved for themselves and which they hold for her for the future.

Keiko Furukura has been working at her local Smile Mart convenience store for half her life, for the eighteen years since she finished high school, and she is completely comfortable in her job and in her ability to manage her life. Though she works only part-time because she says she is “not strong,” she knows where everything belongs in the store, how to restock shelves and supplies, how to update displays, and how to avoid conflict with her co-workers and customers. She likes her job, they like her, she never gets angry, and she is as happy as she can be in her role – one which that she regards as “not suitable for men.” It is the other women in her life who eventually begin to question her role at the store and her future there. She is, after all, a woman in her mid-thirties, approaching the age at which she may soon be “unable” to marry and have children, goals her family and friends have already achieved for themselves and which they hold for her for the future.

In a short, simple narrative very revealing of the main character, her satisfactions, and her lack of aspirations, author Sayaka Murata details the life of a woman who is, unlike most female main characters, someone who is completely happy, satisfied with her job, and not interested in change. She has never had any particular interest in being married or having children, and it is not until she offers to help a friend prepare a barbecue for over a dozen people that she realizes that only two other women there are not yet married. As she describes it, “I hadn’t thought anything of it since not everyone had come as a couple, but unmarried Miki whispered to me: ‘We’re the only ones here who can’t hold our heads up high, aren’t we?’ ” Keiko’s life changes, however, when the convenience store hires a middle-aged man who is shabbily dressed, does not follow directions, disrespects the job, insults Keiko, and arrives late to work. When she asks him what is his reason for working there at all, he admits to her that that he is “marriage-hunting,” looking for someone who has money to invest in his business. As he puts it, “We men have it much harder than women, you know. If you’re not yet a fully fledged member of society, then it’s get a job, and if you’ve got a job, it’s earn more money, and if you earn more money, it’s get married and have offspring. Society is continually judging us. Don’t lump me together with women. You lot have a cushy time of it.”

In a short, simple narrative very revealing of the main character, her satisfactions, and her lack of aspirations, author Sayaka Murata details the life of a woman who is, unlike most female main characters, someone who is completely happy, satisfied with her job, and not interested in change. She has never had any particular interest in being married or having children, and it is not until she offers to help a friend prepare a barbecue for over a dozen people that she realizes that only two other women there are not yet married. As she describes it, “I hadn’t thought anything of it since not everyone had come as a couple, but unmarried Miki whispered to me: ‘We’re the only ones here who can’t hold our heads up high, aren’t we?’ ” Keiko’s life changes, however, when the convenience store hires a middle-aged man who is shabbily dressed, does not follow directions, disrespects the job, insults Keiko, and arrives late to work. When she asks him what is his reason for working there at all, he admits to her that that he is “marriage-hunting,” looking for someone who has money to invest in his business. As he puts it, “We men have it much harder than women, you know. If you’re not yet a fully fledged member of society, then it’s get a job, and if you’ve got a job, it’s earn more money, and if you earn more money, it’s get married and have offspring. Society is continually judging us. Don’t lump me together with women. You lot have a cushy time of it.”

Turning the structure of the typical romance on its head, author Murata then introduces complications to Keiko’s life, reversing the usual societal expectations as Keiko tries to help a man who constantly insults her and contributes nothing to a relationship. Her family and friends, however, see only the surface of what they regard has her budding love life, and they are thrilled for her, even as she deals with a man whose goal in life is to be supported and do nothing. They want her new male friend to attend social functions with her, even as his verbal abuse of her is so outrageous that no reader will believe that any woman, no matter how desperate, would put up with it. She has made her own deal, however, and will let it play out.

The scenes here are so visual that they beg to be included in a short film. Japanese culture, which in many key areas here is similar to American culture, also reveals a kind of patience and respect for tradition here which few American women would be likely to tolerate. Siraha, a male with extreme views who enters Keiko’s life through his job at the convenience store, believes that his society has not changed since the Stone Age, though Keiko proves that belief wrong by actually listening to him instead of hitting him over the head with a Stone Age club. Banging his fist on the table and spilling his tea, he insists, however, that “This society hasn’t changed one bit. People who don’t fit into the village are expelled: men who don’t hunt, women who don’t give birth to children. For all we talk about modern society and individualism, anyone who doesn’t try to fit in can expect to be meddled with, coerced, and ultimately banished from the village….We live in a world which is basically the Stone Age with a veneer of contemporary society.” Keiko herself reveals her lack of thought about the implications for the future with her own simplistic conclusion, that “[Stone Age life] was probably the same as the convenience store, where it was just us being continually replaced while the store remained the same unchanging scene.”

Murata’s satiric humor is similar to that of some of the classical writers of Japan, with ironies and clever twists not unlike those found in some novels by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886 – 1965), one of Japan’s most famous and respected twentieth century novelists. Almost a hundred years ago, Tanizaki was writing about the changes in traditional Japanese society as a result of western contact, and Some Prefer Nettles (1929) and A Cat, a Man, and Two Women (1935), especially, highlight similar issues to those of this novel. Obviously, many changes have occurred in Japanese society since then, and recent novels by contemporary Japanese authors, especially by some female authors, show a society recognizing the changes that have occurred in the past hundred years while also showing the care the country takes to preserve their long traditions of civilization and behavior. Contemporary Japanese writers recognize the freedom which women have achieved within society, and readers interested in pursuing this and other cultural themes may want to click the “Japan” link in the right column of the Home page for links to reviews of twenty-eight other Japanese novels, many of them contemporary. Murata herself is obviously comfortable in her own personal life – she has won major writing prizes, such as the Akutagawa Prize for this novel and was Vogue Japan’s Woman of the Year in 2016 – and she still works by choice in a local convenience store!

Murata’s satiric humor is similar to that of some of the classical writers of Japan, with ironies and clever twists not unlike those found in some novels by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886 – 1965), one of Japan’s most famous and respected twentieth century novelists. Almost a hundred years ago, Tanizaki was writing about the changes in traditional Japanese society as a result of western contact, and Some Prefer Nettles (1929) and A Cat, a Man, and Two Women (1935), especially, highlight similar issues to those of this novel. Obviously, many changes have occurred in Japanese society since then, and recent novels by contemporary Japanese authors, especially by some female authors, show a society recognizing the changes that have occurred in the past hundred years while also showing the care the country takes to preserve their long traditions of civilization and behavior. Contemporary Japanese writers recognize the freedom which women have achieved within society, and readers interested in pursuing this and other cultural themes may want to click the “Japan” link in the right column of the Home page for links to reviews of twenty-eight other Japanese novels, many of them contemporary. Murata herself is obviously comfortable in her own personal life – she has won major writing prizes, such as the Akutagawa Prize for this novel and was Vogue Japan’s Woman of the Year in 2016 – and she still works by choice in a local convenience store!

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://twitter.com

The photo of a convenience store clerk is from https://www.gettyimages.co.uk

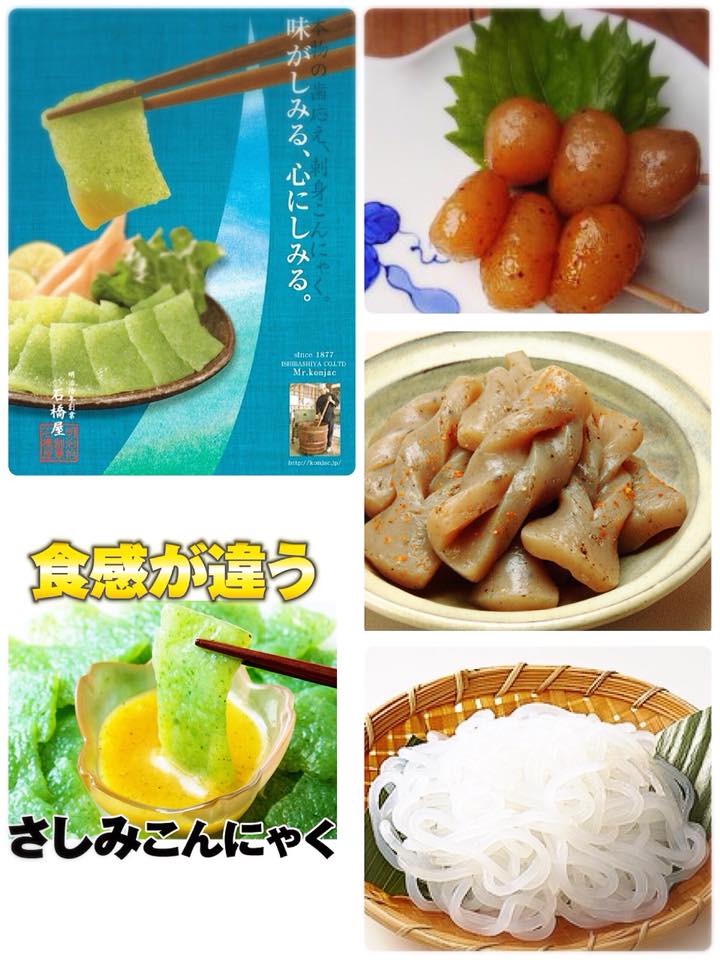

The food picture and the picture of the shelves are both posted on Smile Mart Japan’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/

In her debut novel, just translated and published in English, Norwegian author Gunnhild Oyehaug explores many facets of love among three different women and their lovers, a novel which led in her own country to her involvement with the acclaimed film “Women in Oversized Men’s Shirts” in 2015, based on a repeating image throughout this novel. Here men believe that women in oversized men’s shirts – and little else – are inherently attractive, and most of the female characters find themselves in oversize men’s shirts or pajama tops at some point in the novel as they search for the perfect love. The primary character, Sigrid, a literature graduate, has an inner life that “seems luminous, only not many people have seen it, her secret, sparkling life.” For certain, her present love, Magnus, an older man, does not recognize it. Just recently, twenty-three-year-old Sigrid was wandering around the city, and rather than face going into a café alone, she decided instead to go to a bookshop, where she randomly chose a book with the “life-affirming” title An Empty Chair, and when she looked at the picture of the author on the back, “she met the eyes of the author, Kare Tryvle. Yes, that was exactly what happened she felt that he met her eyes…[and] it was as if they saw deep inside her…saw her infinite loneliness [that] had been there in the bookshelf. Eyes that seemed to say: hello you.”

In her debut novel, just translated and published in English, Norwegian author Gunnhild Oyehaug explores many facets of love among three different women and their lovers, a novel which led in her own country to her involvement with the acclaimed film “Women in Oversized Men’s Shirts” in 2015, based on a repeating image throughout this novel. Here men believe that women in oversized men’s shirts – and little else – are inherently attractive, and most of the female characters find themselves in oversize men’s shirts or pajama tops at some point in the novel as they search for the perfect love. The primary character, Sigrid, a literature graduate, has an inner life that “seems luminous, only not many people have seen it, her secret, sparkling life.” For certain, her present love, Magnus, an older man, does not recognize it. Just recently, twenty-three-year-old Sigrid was wandering around the city, and rather than face going into a café alone, she decided instead to go to a bookshop, where she randomly chose a book with the “life-affirming” title An Empty Chair, and when she looked at the picture of the author on the back, “she met the eyes of the author, Kare Tryvle. Yes, that was exactly what happened she felt that he met her eyes…[and] it was as if they saw deep inside her…saw her infinite loneliness [that] had been there in the bookshelf. Eyes that seemed to say: hello you.”

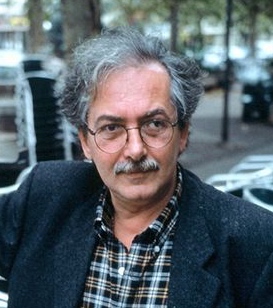

When Jean-Claude Izzo published Total Chaos in France in 1995, he had no way of knowing that this and the two sequels he published shortly afterward would come to be known as the Marseilles Trilogy. Nor would he know that these three books would wait twenty years to be translated and re-published in the US and the UK. A consummately noir author at a time in which hard-boiled noir writing was more generally associated with film than with novels, Izzo, the son of an Italian father who emigrated to France, sets his novels in Marseilles, a city very different from the settings of other noir writers, such as William McIlhenny’s Glasgow, home of the Laidlaw novels in the 1970s, and more recently, Massimo Carlotto’s Padua, Maurizio de Giovanni’s Naples, and Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo’s Scandinavia.

When Jean-Claude Izzo published Total Chaos in France in 1995, he had no way of knowing that this and the two sequels he published shortly afterward would come to be known as the Marseilles Trilogy. Nor would he know that these three books would wait twenty years to be translated and re-published in the US and the UK. A consummately noir author at a time in which hard-boiled noir writing was more generally associated with film than with novels, Izzo, the son of an Italian father who emigrated to France, sets his novels in Marseilles, a city very different from the settings of other noir writers, such as William McIlhenny’s Glasgow, home of the Laidlaw novels in the 1970s, and more recently, Massimo Carlotto’s Padua, Maurizio de Giovanni’s Naples, and Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo’s Scandinavia.

In a novel about the French intellectual elite who live confidently and proudly on the fringes of society in the early twentieth century, author Rupert Thomson explores the lives and loves of two such women who live on their own terms. Avant-garde in their personal beliefs throughout their lives, they become close friends upon their first meeting in 1909 when Lucie Schwob is fourteen and Suzanne Malherbe is seventeen. Soon they are almost inseparable, as they quickly develop very strong feelings for each other. Of the two, Suzanne is more stable, with Lucie dealing with anorexia and other issues, and it is Suzanne, who, at Lucie’s father’s request, accompanies Lucie when she needs to go to a convalescent home for several weeks in an effort to recover from a suicide attempt as a young teen.

In a novel about the French intellectual elite who live confidently and proudly on the fringes of society in the early twentieth century, author Rupert Thomson explores the lives and loves of two such women who live on their own terms. Avant-garde in their personal beliefs throughout their lives, they become close friends upon their first meeting in 1909 when Lucie Schwob is fourteen and Suzanne Malherbe is seventeen. Soon they are almost inseparable, as they quickly develop very strong feelings for each other. Of the two, Suzanne is more stable, with Lucie dealing with anorexia and other issues, and it is Suzanne, who, at Lucie’s father’s request, accompanies Lucie when she needs to go to a convalescent home for several weeks in an effort to recover from a suicide attempt as a young teen.