“This isn’t writing…It is just fiddling about with words…Whatever I do someone else has always done it before, and better. In ten years’ time no one will remember this book, the libraries will have sold off all their grubby copies of it second-hand, and the rest will have gone to dust…And, even if I were one of the great ones, who, in the long run, cares? People walk about the streets and it is all the same to them if the novels of Henry James were never written.”—Beth Cazabon, aspiring author.

Always concerned with writers and writing, author Elizabeth Taylor (1912 – 1975) is, herself, a unique gem, a consummate though unpretentious writer who more than holds her own with better known twentieth century women authors like Muriel Spark, Penelope Lively, Fay Weldon, Jane Gardam, and Beryl Bainbridge, all of whom had the good fortune to have been born a generation later than she. In an especially unfortunate and sadly ironic twist, Taylor’s first novel, At Mrs. Lippincote’s, published in 1945, did not appear in print until she was thirty-three, and by then, a twelve-year-old film star who shared her name had already appeared in five big films, including National Velvet, receiving constant praise and national publicity for her work. Ten years later, the author had published four more outstanding novels and a number of well-reviewed short stories; the beautiful film star, now an adult, had, by contrast, appeared in twenty more films and had become the regular subject of newspaper columns, worldwide.

Always concerned with writers and writing, author Elizabeth Taylor (1912 – 1975) is, herself, a unique gem, a consummate though unpretentious writer who more than holds her own with better known twentieth century women authors like Muriel Spark, Penelope Lively, Fay Weldon, Jane Gardam, and Beryl Bainbridge, all of whom had the good fortune to have been born a generation later than she. In an especially unfortunate and sadly ironic twist, Taylor’s first novel, At Mrs. Lippincote’s, published in 1945, did not appear in print until she was thirty-three, and by then, a twelve-year-old film star who shared her name had already appeared in five big films, including National Velvet, receiving constant praise and national publicity for her work. Ten years later, the author had published four more outstanding novels and a number of well-reviewed short stories; the beautiful film star, now an adult, had, by contrast, appeared in twenty more films and had become the regular subject of newspaper columns, worldwide.

The universality of her themes and the agelessly elegant prose of Elizabeth Taylor-the-author, however, have survived the passage of four decades since her death in 1975, and her novels have been reappearing regularly in a series of reprints by Virago Books in the UK and New York Review Books in the US over the past ten years. Taylor’s character Beth Cazabon may comment grimly about the fickleness of fame and its unimportance in the quotation which opens this review, but Elizabeth Taylor herself has, with her own work, given the lie to her dire predictions about the dark fate which awaits even the best of authors. Caustic critic/author Philip Hensher, famed for writing “the nastiest review ever published,” has even gone so far as to describe Elizabeth Taylor as “one of the hidden treasures of the English novel.”

A View of the Harbour (1947), her third novel, employs the broadest focus of the four novels I have read by Taylor. Whereas the last and most famous novel published in her lifetime, Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont (1971) concentrates on one elderly woman, Mrs. Palfrey, who befriends a callow young man and teaches him about love, the much earlier A View of the Harbor reconstructs an entire community and its citizens – whole families and lonely single residents – as Taylor reveals the values they celebrate – or, at least, observe – in their search for love and connection. This creates challenges for the reader, initially, since s/he must try to remember the specific identities of a wide variety of townspeople, along with the relationships among them, relationships which are constantly changing as the game of love begins in earnest.

Bertram Hemingway, a retired Navy man who has never married, is a free spirit who wants to be an artist and who hints that he is interested in finding a woman. Tory Foyle, a divorced woman, formerly married to a wealthy out of-towner, is the liveliest woman in the community and is a  school friend of Beth Cazabon, a writer who is married to Robert, the town physician. Beth is the mother of two daughters – Prudence, a cross-eyed girl who has never been kissed, recently out of school, and Stevie, about six, who is spoiled. Beth is hoping that that newcomer Geoffrey Lloyd, the son of one of her own school friends, will be a suitor for Prudence. In the meantime, Beth’s friend Tory is having an affair with Robert, Beth’s husband. At a different level of society, is Mrs. Bracey, who is bed-ridden by a debilitating and possibly fatal illness. She and her daughters, Maisie and Iris, sometimes take in boarders like Eddie Flitcroft, who is interested in Maisie. Lily Wilson, a pathetic and lonely young widow, lives in an apartment above the decaying Wax Works which has been in her family for years but which has fallen on hard times. Shy and naive, she becomes interested in several men whom she believes will assuage her loneliness without making too many demands.

school friend of Beth Cazabon, a writer who is married to Robert, the town physician. Beth is the mother of two daughters – Prudence, a cross-eyed girl who has never been kissed, recently out of school, and Stevie, about six, who is spoiled. Beth is hoping that that newcomer Geoffrey Lloyd, the son of one of her own school friends, will be a suitor for Prudence. In the meantime, Beth’s friend Tory is having an affair with Robert, Beth’s husband. At a different level of society, is Mrs. Bracey, who is bed-ridden by a debilitating and possibly fatal illness. She and her daughters, Maisie and Iris, sometimes take in boarders like Eddie Flitcroft, who is interested in Maisie. Lily Wilson, a pathetic and lonely young widow, lives in an apartment above the decaying Wax Works which has been in her family for years but which has fallen on hard times. Shy and naive, she becomes interested in several men whom she believes will assuage her loneliness without making too many demands.

When a sailor from the French Navy arrives in the pub where Lily is having a drink, her innocence and desperation become clear.

Once the reader becomes familiar with this large cast of characters, the action devolves into an unusual kind of farce in which the author is more interested in illustrating the often absurd ways in which people seek love and connection than in laughs for the sake of laughs. In fact, any humor involved in this farce is often bittersweet, more ironic than overt, with characters facing unhappiness and dashed hopes as often as they may find some kind of minimal happiness. The mores of the times and the values of the community – at many different levels – provide points to ponder as the action develops, with Taylor working with a light touch to leaven the claustrophobia inherent in small town life: Beth, the author, has almost finished her latest book, and says she will never write another: “The end of authorship will begin the season of miracles,” she hopes. Later, however, she finds a disappointing review of her book “wrapped around the cod” she brings home. Lily lives a deadly life above the wax museum and looks forward to having someone real to walk her to her upstairs room. Mrs. Bracey, from her sickbed, makes some surprising conclusions about life as her own winds down: “In the things that really matter to us, we are entirely alone. Especially alone dying.” The conclusion comes as a total surprise and provides the final irony.

Those who have read other novels by Taylor will find this one to be fascinating for its broad scope, well developed themes, and ironic twists and turns. Her later novels, far more focused, emphasize one or two main characters as they face crises in their lives, often dealing with love and death. Those who have never read Taylor might want to start with one of her later novels first, my own favorite being Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont.

ALSO by Taylor: A GAME OF HIDE AND SEEK, ANGEL,

MRS. PALFREY AT THE CLAREMONT,

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.biography.com/

This view across the harbor may be found here: http://likecool.com/ The site is in Whitby. The author does not specify a town for the action in this book, though one of the fishing boats indicates that it is based in Newby.

Trawlers were legion in this town: http://trawlerphotos.co.uk/

The photo of a French Navy sailor is from https://www.pinterest.com/ When a sailor from the French Navy arrives in the pub where Lily, a young widow, is having a drink, her innocence and desperation become clear.

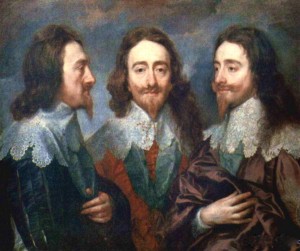

Setting his novel in the north of England in the early 1630s, Irish author Ronan Bennett artfully captures the political, social, and religious turmoil during the reign of King Charles I. Charles, married to a Catholic bride, though England is officially Protestant, has spent his time warring against Spain, and he has committed the cardinal sin—he has lost. He has also been a distant and autocratic king, failing to take into account the enormous religious changes sweeping both Europe and England and undermining his own power. Though England separated from the Catholic Church during the reign of Henry VIII, a hundred years before, grassroots movements wanting stricter accountability for sins have now sprung up, and many local leaders, both religious and civil, are calling for reform and purification.

Setting his novel in the north of England in the early 1630s, Irish author Ronan Bennett artfully captures the political, social, and religious turmoil during the reign of King Charles I. Charles, married to a Catholic bride, though England is officially Protestant, has spent his time warring against Spain, and he has committed the cardinal sin—he has lost. He has also been a distant and autocratic king, failing to take into account the enormous religious changes sweeping both Europe and England and undermining his own power. Though England separated from the Catholic Church during the reign of Henry VIII, a hundred years before, grassroots movements wanting stricter accountability for sins have now sprung up, and many local leaders, both religious and civil, are calling for reform and purification. s from criminal acts. Though he attends the prescribed protestant church, Brigge is in reality one of the “papistical malignants” that the local vicar constantly rails against, a man who must walk the difficult line between the Puritanism of the Master, who is an old friend, and his own Catholicism and the belief that “men must have mercy, for without mercy we are savages.”

s from criminal acts. Though he attends the prescribed protestant church, Brigge is in reality one of the “papistical malignants” that the local vicar constantly rails against, a man who must walk the difficult line between the Puritanism of the Master, who is an old friend, and his own Catholicism and the belief that “men must have mercy, for without mercy we are savages.” While he is in town, Brigge notices that many of the jurymen wear blue threads on their collars and is shocked to discover that these signify their support for Lord Savile, whom Challoner, the Master, has replaced. Convinced, in retrospect, that Savile was less harsh than the current Master and his governors, these men constitute a considerable threat to the Master’s “great project.” Worried that “the better sort” are leaving town because of the high assessments, Challoner cuts taxes by sixty percent, and when one governor points out that this will mean that the poor, who are already near death from starvation, will not then receive their doles, another points out that the Poor Law “is now the mother of idleness. The law should be: he that will not work, let him not eat.” As there is no work, this is a death sentence.

While he is in town, Brigge notices that many of the jurymen wear blue threads on their collars and is shocked to discover that these signify their support for Lord Savile, whom Challoner, the Master, has replaced. Convinced, in retrospect, that Savile was less harsh than the current Master and his governors, these men constitute a considerable threat to the Master’s “great project.” Worried that “the better sort” are leaving town because of the high assessments, Challoner cuts taxes by sixty percent, and when one governor points out that this will mean that the poor, who are already near death from starvation, will not then receive their doles, another points out that the Poor Law “is now the mother of idleness. The law should be: he that will not work, let him not eat.” As there is no work, this is a death sentence. make the Puritan characters come alive, despite their excesses, while John Brigge, a man who sees more than one side to each issue, becomes a protagonist for whom the reader develops much sympathy.

make the Puritan characters come alive, despite their excesses, while John Brigge, a man who sees more than one side to each issue, becomes a protagonist for whom the reader develops much sympathy.