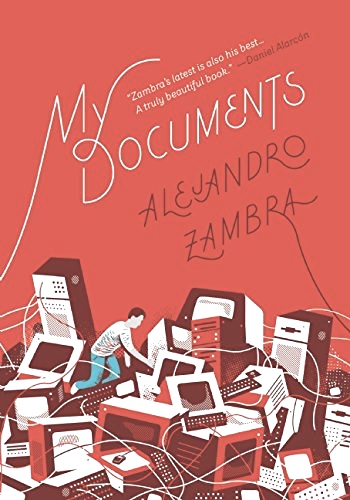

Note: Author Alejandro Zambra was WINNER of Chile’s National Critics’ Prize for his novella, Bonsai, in 2006.

“It’s nighttime, it’s always nighttime when the text comes to an end. I re-read, rephrase sentences, specify names. I try to remember better: more, and better. I cut and paste, change and enlarge the font, play with line spacing. I think about closing this file and leaving it forever in the My Documents folder. But I’m going to publish it, I want to, even though it’s not finished, even though it’s impossible to finish it.”—the author, in his story “My Documents.”

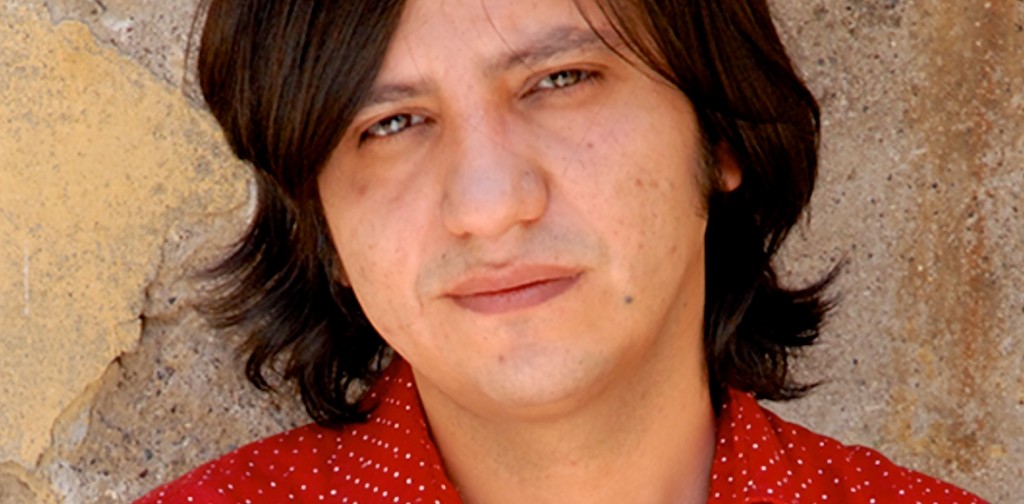

Described as “the greatest writer of Chile’s younger generation,” author Alejandro Zambra has created eleven stories so firmly grounded in reality and filled with carefully chosen detail that they seem to be from his own life, though it is impossible to know for sure without hearing more from the author himself. Likewise, we cannot know how much may be inspired by his own life but altered for the purpose of improving the story, or how much may be created from whole cloth for the purpose of recreating a period in history or illustrating a theme. Ultimately, this collection of stories vibrantly recreates an unusual childhood from the perspective of a child, while also revealing the speaker’s early adulthood and his lack of confidence in his own maturity. In several stories, the author conveys the feelings at the heart of parent-child relationships, from the points of view of both; political revolution and trauma lurk in the background throughout all the stories. As he wrestles with his stories and how to present the personal and community values of Chile during this period in the late twentieth century, the author also contributes much to our understanding of the art of writing itself. Ultimately, these intense, compressed, clear, and unpretentious stories breathe with quiet life, focused on reality as a simple, if sometimes heart-breaking, concept.

Described as “the greatest writer of Chile’s younger generation,” author Alejandro Zambra has created eleven stories so firmly grounded in reality and filled with carefully chosen detail that they seem to be from his own life, though it is impossible to know for sure without hearing more from the author himself. Likewise, we cannot know how much may be inspired by his own life but altered for the purpose of improving the story, or how much may be created from whole cloth for the purpose of recreating a period in history or illustrating a theme. Ultimately, this collection of stories vibrantly recreates an unusual childhood from the perspective of a child, while also revealing the speaker’s early adulthood and his lack of confidence in his own maturity. In several stories, the author conveys the feelings at the heart of parent-child relationships, from the points of view of both; political revolution and trauma lurk in the background throughout all the stories. As he wrestles with his stories and how to present the personal and community values of Chile during this period in the late twentieth century, the author also contributes much to our understanding of the art of writing itself. Ultimately, these intense, compressed, clear, and unpretentious stories breathe with quiet life, focused on reality as a simple, if sometimes heart-breaking, concept.

The long opening story, “My Documents,” clearly establishes the time, place, characters, and atmosphere by introducing the main character at age four or five, when, in 1980, he sees a computer for the first time, an enormous machine used by his father, quite different from the electric typewriter of his father’s secretary, or the black Olivetti on which his mother does her typing work, transcribing songs, stories, and poems written by his grandmother. The speaker learns how to type his name but prefers using the keyboard to imitate drumrolls instead, remembering the drum major in the marching band at his school, before veering off into a discussion of his Catholic education, the music of Simon and Garfunkel, and the local competitions in kite-flying and the tricks used to win. By 1986, the speaker tells us, he has lied to become an altar boy, a task he honors for over a year while convinced he is going to die because he has been taking Communion “illegally.”

Margaret Thatcher was a friend of Augusto Pinochet during his whole career, selling him weapons and providing supplies for Chile during the Falklands War in 1982. Richard Nixon was also a supporter of Pinochet.

This extended story continues with speaker’s first “adult” discovery in 1986 when, at age eleven, he learns of Augusto Pinochet’s human rights abuses of citizens who were arrested, tortured, murdered, or disappeared. These crimes are described peripherally, with occasional additional references throughout the book, during Pinochet’s dictatorship from 1973 – 1990, and up to 1998 while he was still Commander in Chief of the army. In college by 1994, the speaker is on his own by 1997, and by 1999, he has bought his first computer, an immense Olidata. In 2013, when he is in his late thirties, this chapter ends. The author announces that he has now completed this book, and as he ponders the idea of simply closing his My Documents file, he determines to publish it instead, announcing that “My father was a computer, my mother a typewriter. I was a blank page, and now I am a book.”

Famed Chilean goalie Condor Rojas was a hero to the speaker and Camilo, until he participated in a hoax during a championship game against Brazil in 1989 . See photo credits for more information.

The story “Camilo” follows a similar pattern to that of the first story, “My Documents,” in that it begins when the speaker is very young and ends decades later. The speaker is nine when Camilo shows up at their gate and explains that he is the speaker’s father’s godson. With an interest in rock bands, rather than soccer, which the speaker and his father watch every week, Camilo and the speaker have little in common, but Camilo is a gregarious teenage friend who soon becomes “a benevolent and protective presence.” In return the speaker and his father take Camilo to soccer games, which the speaker’s father and Camilo’s father had played together. Gradually, we learn that Camilo is helping the young speaker with his problems with obsessive compulsive disorder. Eventually, the boys attend the Chile-Brazil playoffs leading to the World Cup in 1990, rooting wildly for Condor Rojas, Chile’s goalie, the speaker’s favorite player because his own father plays that position on a local team. A devastating scandal which arises regarding Rojas, is discussed further, with photos, in the link given in the footnotes here. Camilo later goes to France to reconnect with his father, and, twenty-two years later, the speaker meets with Camilo’s father in Amsterdam. Moving and thoughtful, the story carries a message about time and chance which will resonate with all readers.

While he is trying to give up smoking, the speaker must deal with migraines. He finds Oliver Sachs's book, Migraine, especially helpful.

Subsequent stories deal with the fact that most of us are alone most of the time. “True or False,” concerns a divorced man whose son visits every two weeks. The boy considers his father’s house to be the “false house” and his mother’s house to be the “true house.” Knowing this, the father gets a cat to make the house feel more like home, but when the cat later has kittens, a problem arises, and leads to a surprise conclusion. “I Smoked Very Well,” one of my favorites, is about a writer who decides to give up smoking and discovers that it affects the whole writing process, the reading process, and the general socializing that provides inspiration for his work. “Family Life” and “Thank You” deal with situations in which women become victims who have too little control over their destinies, which are controlled by men, sometimes because the women allow it. “Artist’s Rendition,” another story about writing, deals with a reality which becomes fiction while the fiction becomes reality.

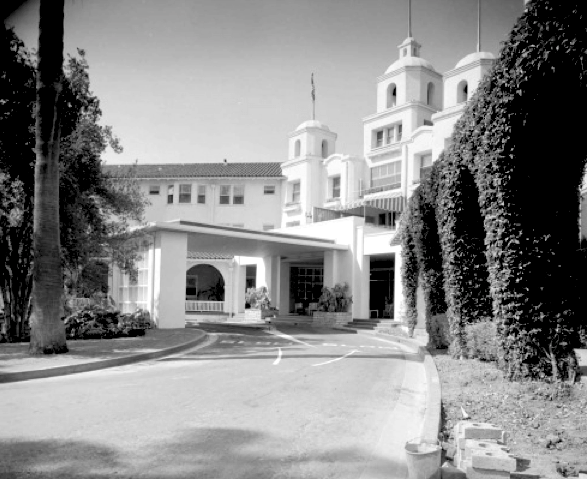

In "The Most Chilean Man in the World," the main character goes to Leuven, Belgium, where he contemplates this bizarre fountain in which a stylized figure tries to find the formula for happiness in a book.

Six of these stories, told from the first person point of view, and five from the third person, are grouped to suggest that the first person stories really are about the author’s own life while the third person stories are about life as Zambra would interpret it if he were the main character. His first person narrators speak intimately, as if the author is addressing his reader directly, while the third person, more distanced, expands the author’s themes, ideas, and images beyond the realm of his own life into the wider world. In this way, he creates a kind of déjà vu for the reader by filling his narrative with small details his characters remember because of their personal importance at a particular place and time, and most readers will immediately recognize the parallels from their own lives in the small images which forever stick in their own minds and bring back major events. This extraordinary and profound collection makes writing look easy. If you love good writing with an unusual series of unpretentious voices and a surprising amount of humor and irony, don’t miss this.

ALSO by Alejandro Zambra: THE PRIVATE LIVES OF TREES

A special note of congratulations to translator Megan McDowell, who was also the translator for THE PRIVATE LIVES OF TREES. Translating a book in which the author has been particularly careful in his own word choice requires enormous care from the translator to convey the same feelings and images.

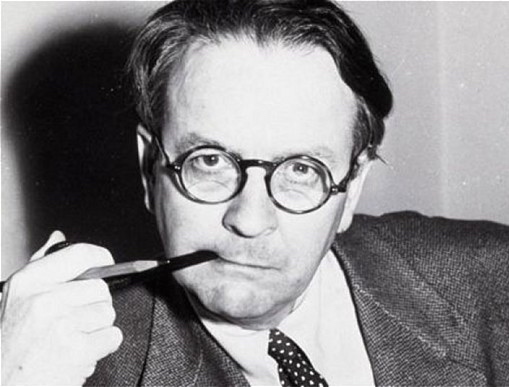

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.vice.com

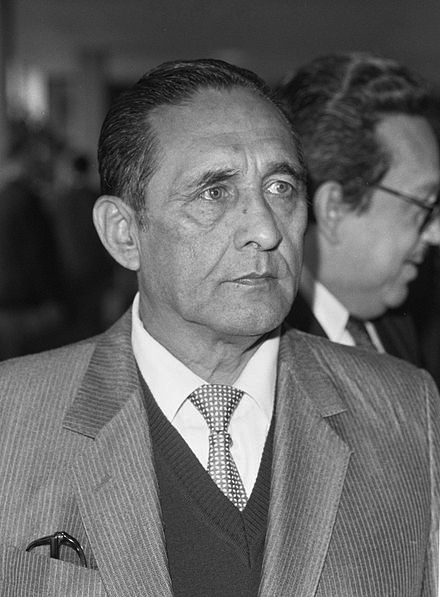

Margaret Thatcher was a friend of Augusto Pinochet during his whole career, selling him weapons and providing supplies for Chile during the Falklands War in 1982. He was arrested in England on a warrant from Spain for human rights abuses in 1998 and spent 1 1/2 years in prison in the UK. After his release he was under house arrest in Chile for the rest of his life. He died in 2006. The US under Richard Nixon was also a supporter of Pinochet. Photo from: http://www.ibtimes.com/

The story of the hoax perpetrated by Condor Rojas during a championship game against Brazil in 1989, may be found here: http://colgadosporelfutbol.com/la-mayor-farsa-de-la-historia-del-futbol/. The photo posted here is from http://www.fotolog.com

Migraine by Oliver Sachs was helpful to the speaker when he was dealing with migraines during his efforts to give up smoking in “I Smoked Very Well.” See http://en.wikipedia.org/

When Rodrigo in “The Most Chilean Man in the World” goes to Leuven, Belgium, in pursuit of a woman, he spends time looking at this bizarre little fountain which shows a stylized boy/man reading a book in which he is hoping to gain the secret of happiness. Photo from https://lenzu.wordpress.com

ARC: from McSweeney’s