Note: Winner of many literary prizes in his home country of France, Patrick Modiano was also WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014.

“I found myself at the Chatelet metro station at peak hour….There was a woman wearing a yellow coat….She was so like my mother that I thought it must be her….She had the same profile as my mother, that distinctive nose, slightly upturned. The same bright eyes. The same high forehead. She hadn’t changed much….Her mouth was set in a bitter grimace. [Now] I was certain it was her.” Therese, age nineteen.

In an unusual twist, author Patrick Modiano uses a young woman, Therese, as his main character in this intense and seductive novel of identity. Few readers of his novels, however, will notice much difference in her thinking from that of the young men who are also searching for identity in many of Modiano’s other novels. Her isolation from her parents is like theirs – and like that of Modiano himself as he has described his childhood and early teens. At age nine, Modiano was essentially abandoned by his parents and given over to a group of young circus acrobats to raise. He did not see his parents for two years, except when his father occasionally appeared late at night for secret “meetings” related to smuggling he was doing for the French Gestapo. The arrest of the acrobats left Modiano alone, and he ended up in boarding schools with no parental guidance. There he used his prodigious writing skills as an outlet for his emotions, eventually attracting the attention of author Raymond Queneau, who became his mentor.

In an unusual twist, author Patrick Modiano uses a young woman, Therese, as his main character in this intense and seductive novel of identity. Few readers of his novels, however, will notice much difference in her thinking from that of the young men who are also searching for identity in many of Modiano’s other novels. Her isolation from her parents is like theirs – and like that of Modiano himself as he has described his childhood and early teens. At age nine, Modiano was essentially abandoned by his parents and given over to a group of young circus acrobats to raise. He did not see his parents for two years, except when his father occasionally appeared late at night for secret “meetings” related to smuggling he was doing for the French Gestapo. The arrest of the acrobats left Modiano alone, and he ended up in boarding schools with no parental guidance. There he used his prodigious writing skills as an outlet for his emotions, eventually attracting the attention of author Raymond Queneau, who became his mentor.

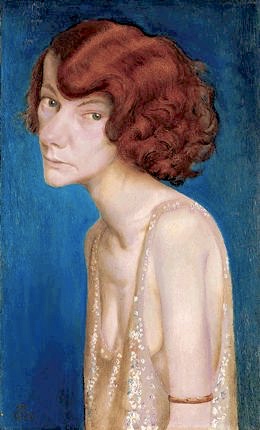

Therese, who is about nineteen as this novel opens, has had a similar experience. Put on a train as a six-or-seven-year-old child, with a sign around her neck directing those in charge to take her to a woman in the countryside for care, she was abandoned by her mother. Herself an actress like Modiano’s own mother, Therese’s mother had assumed several different names during Therese’s early childhood. Years later, even if Therese had been able to mount a search for her mother, she would have had no idea what name her mother might be using. She left behind only a portrait of herself and a small metal box containing a diary, a notebook of contacts, and a few jottings on paper. Periodically, Therese would look through this assortment of “stuff,” but the only news she ever heard of her mother was a long-ago report that she had died in Morocco.

Now nineteen, Therese suddenly believes she has seen her mother at the Chatellet metro station, and her longing for information inspires her to follow the woman in the yellow coat as she travels the metro. “I had no desire to speak to her; I felt nothing in particular towards her. Circumstances had prevented us from sharing what people call the milk of human kindness. The only thing I wanted to know was where she had washed up, 12 years after her death in Morocco.” Soon she becomes obsessed with following the woman, going to the train station nearly every day in case the woman appears and then takes the train. As Therese rides the train in pursuit, she reminisces about her childhood nickname, Little Jewel, and her mother’s name Sonia, a made-up name, since Therese knows her real name is Suzanne Carderes. Conversations which Therese later has with the concierge of the apartment building to which woman in the yellow coat returns at night also indicate that the woman is referred to as the Kraut and as Death Cheater by other residents, and that she is behind on the rent. Eventually, Therese musters the courage to go upstairs to the woman’s apartment, where she discovers that the nameplate on the woman’s door reads “Comtesse Sonia O’Dauye.” She does not knock on the door.

The little girl for whom Therese is babysitting had to look out her bedroom window at the Jardin de l’Acclamatation every night, though there was little chance she’d get to go there.

The layers of reality (or fantasy) here quickly begin to accumulate. When Therese eventually gets a job as a babysitter for a lonely young girl, the overlaps between the early life of Therese and the life of the unnamed child begin to combine and blur. The child’s parents fight constantly and disappear at night leaving her alone to feed herself and put herself to bed. They spend no time with her and have no discernible feelings for her. No one is quite sure of their name, and no one knows where they came from or how long they plan to stay. The child’s room, ironically, overlooks the Jardin d’Acclimatation, a children’s park, though she never gets to play there. Soon Therese’s life becomes a balancing act between caring for the child, following the woman with the yellow coat, and enjoying a new relationship with a young man who is able to translate writing and radio commentary into twenty different languages. She feels guilty that she has lied to him about having been to a language school, and she becomes engulfed by the emotional turmoil taking place inside her on many different levels.

At the halfway point in the novel, Therese has her moment of recognition. Overwhelmed and feeling lost, she has been walking around the area by the Gare de Lyon, a place where, as a child, she was sometimes cared for by her “uncle,” Jean Borand, one of the few people who was ever kind to her. As she tries to imagine seeing him again, she realizes that none of the places around the station look familiar to her now. All she can see is the Gare de Lyon and its illuminated clock face, symbolic to the reader on several levels. Suddenly she realizes that “The time had come to make a break…I had to see this through to the end, without really knowing what ‘to the end’ meant.” Looking in the window of a pharmacy, she sees a woman pharmacist’s face, “so different from Death Cheater’s….There was a calmness and grace about her in the soothing glow of the light.” Therese walks inside, her chest feeling as if it is “suffocating her.” The sensitive chemist tends to her, and for the first time in her life Therese shares her real feelings.

As Therese works her way toward a resolution of the many different elements of her conflicts – her mother, her goals for the future, her male translator friend, the child she babysits for, and her fondness for the chemist/pharmacist who has been so helpful to her – she continues to have her ups and downs and the emergencies that go with them. She has never experienced love, parental or otherwise; she has no personal resources on which to draw for strength; she has no real knowledge of how to begin to fix her life; and she is totally alone. Modiano makes Therese’s life real and understandable, making it feel as “normal” for the reader as it is for Therese – a life that might have happened to any one of us – and he seems to suggest that it is only by chance that any of us manage to make it through our lives. Without a trace of sentimentality, Modiano creates one of the most revelatory of all his novels, one that shows the possibilities of resolution and redemption, even for those who have always been alone, a novel that ranks high on my Favorites lisT.

ALSO by Modiano: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, FAMILY RECORD, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (with Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE, PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo on http://www.babelio.com/

The Chatelet metro station where Therese first saw the “woman in the yellow coat” is shown on https://soundlandscapes.wordpress.com/

The little girl for whom Therese is babysitting had to look out her bedroom window at the Jardin de l’Acclamatation every night, though there was little chance she’d get to go there. http://www.lesparisdemma.com/

At the Gare de Lyon, with its iconic clock, Therese begins to come to a recognition regarding her future. http://www.lesparisdemma.com

When Therese finds herself in a “big glass cage, she “looks around. There were aquariums in other glass cages.” http://www.reamaternity.gr

ARC: Yale University

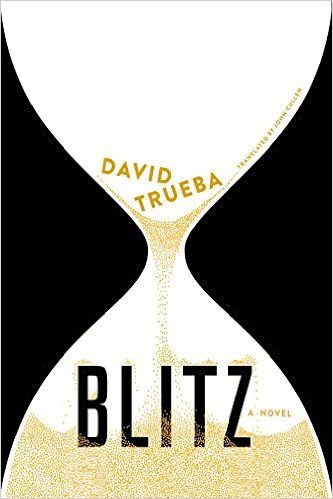

From the outset of this novel, author David Trueba’s ability to visualize and recreate intense word pictures dominates his style, making the reading of this novel a special treat on several different levels. Not only does he show the places and people surrounding his main character, Beto Sanz, instead of simply telling about them, but he also channels Beto’s own inner thoughts, providing lively commentary on virtually every aspect of his life and the activity around him. As the narrative opens, Beto has just arrived in Munich from Madrid for a conference for landscape architects, where his firm is a finalist for an international prize. His project is competing in the category of “landscape intervention, not necessarily feasible or reasonable…[but] something like a fantasy or a fiction.” Beto’s particular innovation is a “forest of human-sized hourglasses…sand clocks, which if you turned them over, accorded you a measured period of time to devote to your own thoughts…a reminder and quantifier of time, but also…an escape.” He is nervous but full of hope as he prepares for his presentation to the jury, after which he and Marta, his partner and lover, will return immediately to Spain.

From the outset of this novel, author David Trueba’s ability to visualize and recreate intense word pictures dominates his style, making the reading of this novel a special treat on several different levels. Not only does he show the places and people surrounding his main character, Beto Sanz, instead of simply telling about them, but he also channels Beto’s own inner thoughts, providing lively commentary on virtually every aspect of his life and the activity around him. As the narrative opens, Beto has just arrived in Munich from Madrid for a conference for landscape architects, where his firm is a finalist for an international prize. His project is competing in the category of “landscape intervention, not necessarily feasible or reasonable…[but] something like a fantasy or a fiction.” Beto’s particular innovation is a “forest of human-sized hourglasses…sand clocks, which if you turned them over, accorded you a measured period of time to devote to your own thoughts…a reminder and quantifier of time, but also…an escape.” He is nervous but full of hope as he prepares for his presentation to the jury, after which he and Marta, his partner and lover, will return immediately to Spain.

“The Alligator’s” metaphorical description of northeast Italy, especially the area around Padua, comes so vividly to life in this series of Mediterranean Noir novels that the reader might be excused for wondering how author Massimo Carlotto obtained his knowledge of crime and criminals. His writing feels true. His thoughts on the judicial system in Italy feel far more sophisticated and far more complex than what one would normally expect to see in a mystery series which has made the author one of the most popular noir novelists in Europe. His own views of what constitutes “justice,” if his main character Marco Buratti, “the Alligator,” can be considered his “voice,” are more “flexible” than those of any other author I can recall reading. At one point in this novel, Buratti, who works as an unlicensed private investigator, comments that “you can’t leave someone alive if he might decide without warning to pump you full of lead or else hire someone else to do it for him.” He adds that “in the underworld, when situations arise that threaten to end in a bloodbath, the thing to do, if possible, is to arrange for negotiations that will at least limit the number of corpses.”

“The Alligator’s” metaphorical description of northeast Italy, especially the area around Padua, comes so vividly to life in this series of Mediterranean Noir novels that the reader might be excused for wondering how author Massimo Carlotto obtained his knowledge of crime and criminals. His writing feels true. His thoughts on the judicial system in Italy feel far more sophisticated and far more complex than what one would normally expect to see in a mystery series which has made the author one of the most popular noir novelists in Europe. His own views of what constitutes “justice,” if his main character Marco Buratti, “the Alligator,” can be considered his “voice,” are more “flexible” than those of any other author I can recall reading. At one point in this novel, Buratti, who works as an unlicensed private investigator, comments that “you can’t leave someone alive if he might decide without warning to pump you full of lead or else hire someone else to do it for him.” He adds that “in the underworld, when situations arise that threaten to end in a bloodbath, the thing to do, if possible, is to arrange for negotiations that will at least limit the number of corpses.”

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Australian Fiction; WINNER of the Patrick White Literary Award, one of Australia’s highest honors; WINNER of the Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, and WINNER of the New South Wales Premier’s People’s Choice Award for 2015.

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Australian Fiction; WINNER of the Patrick White Literary Award, one of Australia’s highest honors; WINNER of the Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, and WINNER of the New South Wales Premier’s People’s Choice Award for 2015.