“It was very hot that summer, and we were sure no one would find us there. In the afternoons we would walk along the embankment to the most crowded part of the beach. Then we would walk down the sand looking for a tiny place free where we could lie on our beach towels….We were like everyone else, there was nothing to set us apart from the others, those Sundays in August.”

Most of Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano’s novels echo with memories of his own early life and his efforts to come to terms with his parents’ abandonment of him before he was even in his teens. This novel is different, however, unique, a stand-alone. Main character Jean is sensitive, observant, and emotionally free to love, as the main characters appear to be in most of Modiano’s other novels, but in this novel, the main character does not feel like a substitute for the author. Instead, Jean is a young, rather naïve young man, caught in circumstances that he regards as more of a mystery than the serious crime that readers may conclude it to be, a conundrum which he does not fully grasp. Jean is almost certainly a pawn in the hands of clever criminals, rather than the victim of childhood traumas which typify Modiano’s main characters in his other novels. The mystery here, which may even include murder, begins after the novel’s action has concluded offstage, as the opening lines of the novel set the scene seven years after the action has taken place. Flashbacks, reminiscences, and overlaps between the events from the past and events in the present take place as Jean and the reader are forced to consider what really happened, especially when some of the earlier characters suddenly reappear in the present.

Most of Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano’s novels echo with memories of his own early life and his efforts to come to terms with his parents’ abandonment of him before he was even in his teens. This novel is different, however, unique, a stand-alone. Main character Jean is sensitive, observant, and emotionally free to love, as the main characters appear to be in most of Modiano’s other novels, but in this novel, the main character does not feel like a substitute for the author. Instead, Jean is a young, rather naïve young man, caught in circumstances that he regards as more of a mystery than the serious crime that readers may conclude it to be, a conundrum which he does not fully grasp. Jean is almost certainly a pawn in the hands of clever criminals, rather than the victim of childhood traumas which typify Modiano’s main characters in his other novels. The mystery here, which may even include murder, begins after the novel’s action has concluded offstage, as the opening lines of the novel set the scene seven years after the action has taken place. Flashbacks, reminiscences, and overlaps between the events from the past and events in the present take place as Jean and the reader are forced to consider what really happened, especially when some of the earlier characters suddenly reappear in the present.

As the novel opens, Jean is alone on the Riviera in Nice, a different environment from Paris, which becomes almost a character in most of Modiano’s other novels. Living in a furnished single room in a residential complex which was once the beautiful Hotel Majestic in Nice, Jean, a photographer, leads a relatively simple life, far different from the Riviera’s glitzy, often superficial activities designed to suit every desire and offer quick solutions for every impulse. The largely transient population creates an oddly shifting morality which makes absolute rules irrelevant in the party scene. Although seven years have passed, Jean remains haunted by events from his past, unable to reconcile his conflicting feelings about them. Then, suddenly, Jean sees a former acquaintance from seven years ago, Frederic Villecourt, on the street, selling elegant leather jackets and fur coats from the back of a van at “American [bargain] prices.” Within a few moments of connecting with Villecourt, Jean and the reader learn that a woman named Sylvia and Villecourt “weren’t actually married. My mother opposed the marriage….She would have cut me off if I had married Sylvia.” Though the background related to this declaration is not clear, at this point, the reader quickly learns that Jean had lived with and shared what he believed to be true love with Sylvia for many months after her time with Villecourt. He cannot understand why she lied to him about her marriage, even continuing to wear her “wedding” ring, insisting that she and Villecourt were married, nor can he believe Villecourt’s insistence that he himself was the only man that Sylvia ever really loved.

The former Majestic Hotel, converted to apartments and rooms, where Jean is living as the novel opens.

Soon another flashback describes the arrival of Sylvia by train in Nice, where Jean has finally found a quiet place for the two of them to live in a small pension. Her arrival is discreet – though discreet, perhaps, only by Riviera standards. Around her neck she is wearing the Southern Cross, a large and magnificent diamond with a storied past. First mentioned in histories as having been stolen from the countess du Barry in 1791, the Southern Cross was later sold in 1795, stolen again in 1917, again in 1943, and once more in 1944. Its owners had been guillotined, murdered, shot, and two had disappeared. The reader soon knows more about the history of this mysterious diamond, in fact, than about the main characters. It is this lack of specific knowledge and the emotional distance among these characters which dramatically increase the suspense, keeping the reader unclear about references and wanting to know more. How did Sylvia get the diamond, where did it come from, who is behind the financing, and what role will Jean play in its potential sale, are among many questions which are never answered directly. Gradually, as the flashbacks delve deeper and deeper into the events which have led to these mysteries, the reader begins to draw his/her own conclusions about characters and their possible motives.

To avoid crowds, Jean and Sylvia often spent time at the playground of the Jardin d’Alsace-Lorraine, watching the children play.

Halfway through the novel, as Jean and Sylvia are exploring their lives together in Nice, following a separation from the rest of the group, Jean declares that “I feel at ease [now] in this city of ghosts where time has stopped,” though he admits “that I have lost a certain resilience…I float like the other inhabitants of Nice.” Looking back at this time from seven years forward, he also sees that “we lurched this way and that to try to fight off the torpor overwhelming us. The only solid, consistent thing in our lives, the sole inalterable point of reference, was the diamond. Had it brought us bad luck?” Slowly, the outside world becomes more persistent in invading the lives that Jean and Sylvia have been guarding, and the need to sell the Southern Cross, becomes more immediate. A potential buyer has been located.

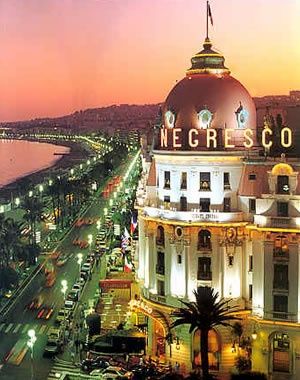

The iconic Negresco Hotel, where Jean meets some characters at the bar, looms over the Promenade des Anglais.

Though the reader knows from the opening of the book, seven years after the events, that Jean is not a winner, nor is Villecourt, who is selling jackets and coats, mysteries still remain, even at the end of the novel, and it is up to the reader to draw conclusions. The atmosphere throughout is “blurry,” as one critic described it, filled with a sense of loss and big questions about life and the immediate past, present, and future. As the novel swirls, incorporating a broad sense of time, rather than a clear beginning, middle, and end, its “conclusion” feels tentative, reflecting the mysteries not only of the novel’s action but of Jean himself and his relationships. Anxiety rules here, and as Jean says, near the end, “our anxiety didn’t come from our contact with that cold stone with glints of blue – it came from life itself,” a conclusion fitting for a novel in which the mysteries outweigh conclusions and life has no easy answers, if any answers at all. One of Modiano’s most unusual novels, Sundays in August is darkly fun to read without being “light,” and thoughtful without being “heavy,” always intriguing in its views of a young main character trying to figure out his confusing world. Sensitively translated by Damion Searles.

ALSO by Modiano: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (with Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay, LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE, PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

NOTE: Readers new to Modiano who are looking for a book which will provide the greatest information about his background and a good introduction to his style may want to begin with SUSPENDED SENTENCES.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo at his Nobel Prize ceremony appears on https://www.nobelprize.org/

The postcard from the Hotel Majestic, now converted into apartments and rooms, where Jean lives at the time the novel opens, is from http://cartepostale-ancienne.fr

The children’s park at the Jardin d’Alsace-Lorraine may be found at https://www.bienici.com

The iconic Hotel Negresco, where Jean meets some characters at the bar, is shown on https://www.pinterest.com/