Note: Jane Gardam has twice been awarded the Costa (Whitbread) Award, and has been honored with the Phoenix Award for Children’s Literature and the Heywood Hill Literature Prize for her lifetime contribution toward the enjoyment of literature.

“All Hetty could think of was ink. There happened to be a bottle of blue-black Quink upon the table….It brought back to Hetty, and perhaps to her father in times past, examination rooms, the joy of easy questions, the knowledge that all the work had paid off. ‘I can do this!’ No joy like it. Page after page of wet, salt ink, blotted, legible, confident. It was ink that had freed her. Blessed ink. Ink for immortality. Stronger than history itself.”

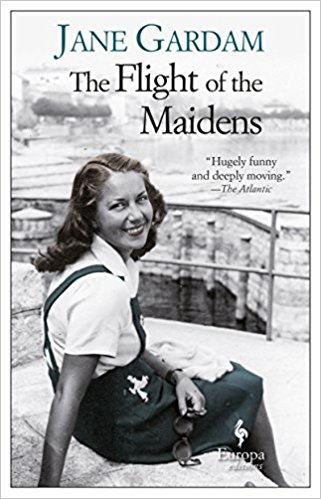

Each new book by Jane Gardam is an homage to her own love of ink. Though a small number of other fine authors may come close to her in terms of prizes, awards, and even titles bestowed by Queen Elizabeth, Jane Gardam stands out among them for the sheer joy of writing which is so obvious in her novels. In The Flight of the Maidens, Jane Gardam is clearly having fun, and no matter how beautifully crafted her characters, how clever her use of irony, how accurate and often unique her descriptions, and how much empathy she may show for those who are having problems coping with the uncertainties of life, it is the “smile” which appears in her work which many of us love and celebrate. The Flight of the Maidens, written originally in 2000 and recently republished by Europa Editions, begins in 1946, as Britain begins its recovery after World War II, a time in which women’s issues began to become better recognized.

Each new book by Jane Gardam is an homage to her own love of ink. Though a small number of other fine authors may come close to her in terms of prizes, awards, and even titles bestowed by Queen Elizabeth, Jane Gardam stands out among them for the sheer joy of writing which is so obvious in her novels. In The Flight of the Maidens, Jane Gardam is clearly having fun, and no matter how beautifully crafted her characters, how clever her use of irony, how accurate and often unique her descriptions, and how much empathy she may show for those who are having problems coping with the uncertainties of life, it is the “smile” which appears in her work which many of us love and celebrate. The Flight of the Maidens, written originally in 2000 and recently republished by Europa Editions, begins in 1946, as Britain begins its recovery after World War II, a time in which women’s issues began to become better recognized.

Here, Gardam tells the stories of three seventeen-year-old girls from Yorkshire who are just finishing their school work. Much of the action surrounds Hetty Fallowes, who is “poor because her father, who had been four years in the trenches in the First World War, had returned miraculously unscathed in body but shattered to bits in mind.” He now works as a grave-digger. She and her gossipy mother do not always get along, and Hetty is not sure that she will be able to get the financial aid she needs for college, but she would like to study literature if she has a choice. Una Vane, “an owl of a child with sober manners who always had clean finger-nails,” lived a typical life until she was nine, when her father, a physician, walked out of his house and never came back. A victim of “the Somme,” her father had later been found dead below the rocks of Boulby Head. She is anxious to study physics at university. Though Hetty Fallowes and Una Vane are friends, the third girl, Liselotte Klein, whom they know but are not close to, has always been an outsider to them, one of the many Jewish children who were smuggled out of Germany in 1939 and “adopted” by people in England who were committed to their schooling. Liselotte has had no confirmation about the fate of her family in Germany, but she looks forward to college and plans to study foreign languages.

As Gardam tells the stories of the three young women – still girls, really – she fills the action with vivid period detail, some of which conveys attitudes and subtle commentary. This is obvious when Hetty is introduced. She first met Eustace, the man in her life, at the vicarage the previous year. She was sixteen, and he was twenty-one, a lance-corporal in the Army, stationed locally. He declared his love after their second meeting, admiring her mind. Their frequent walks during the summer of the action here always involve discussions of books, and when they begin to kiss, at last, Gardam notes that Hetty “had been kissed before, at sweaty school dances and was becoming good at it. Eustace was not adept.” The lively Hetty continues to regard him as a boyfriend, somehow managing to “subdue the recent regret that he never laughed,” and when she picks up his watch band for him at a local watchmakers, she notes that “the leather smelled male. Somehow Eustace had not smelled male. He’d smelled of Wright’s Coal Tar soap.” He does help Hetty study for her entrance exams, however, and when she passes them, the whole world is surprised. As the summer and the pre-college activity involving Una and Liselotte also develops, Hetty’s attachment to Eustace is thrown into sharp relief.

The view from the hostel where Una and Ray stay may be like this one from the Ghyll Mill Hostel in North Yorkshire, within biking distance of where these girls live.

Una Vane has been friendly with Ray, “a sharp-faced boy from the fish shop who belongs to a cycle club, and also with a gigantic girl called Brenda Flange, who has Amazonian shoulders and thighs.” The three of them go out regularly on their racing bikes, and gradually Una, a late bloomer, and Ray become a couple. Their chaste relationship continues, and though Ray eventually becomes a clerk on the London and North Eastern Railway, Una’s mother cannot help feeling that Una “could do a bit better.” Una eventually agrees to go away with Ray for a cycling weekend, where they will stay at a youth hostel in the high hills, where the “brick cottages out of which the youth hostel had evolved possessed one of the most spectacular views in England.” Their trip takes on new meaning when they are surprised to meet another couple there.

Liselotte Stein, whose role is the smallest in the novel, is removed from the Quaker home where she has been living for several years and placed with a Jewish couple which has been rescuing stolen antiques and artifacts, storing them in their house, so crowded with “stuff” that all the inhabitants must sleep on couches. Eventually, Liselotte decides to find out the truth about her family and travels alone to find them.

The novel reaches its climax at the end of summer as all three girls, now more mature, take off for their colleges in London. All have had “flights” from someone or something, and all have grown dramatically during their summer vacations. Gardam has told their stories with sympathy, drama, and plenty of action, making 1946 come alive for the reader. The social and class differences in England play a role in the plots, the reluctance to confront the Nazi terror and its aftermath is evident in the fate of Liselotte, and the importance of an education as an entrée to social acceptance is stressed. The resolutions to the stories of the three girls, however, are heavily dependent upon coincidence, and while Gardam does make the reader care about her characters, they are not as fully developed as they have been in other, less “crowded” Gardam novels. Delightful to read and revelatory of the period, The Flight of the Maidens will keep a reader fully occupied on a long plane ride or at the beach.

ALSO, by Gardam: CRUSOE’S DAUGHTER, GOD ON THE ROCKS, LAST FRIENDS, A LONG WAY FROM VERONA, THE MAN IN THE WOODEN HAT, OLD FILTH, THE PEOPLE OF PRIVILEGE HILL, THE QUEEN OF THE TAMBOURINE.

Photos. The author’s photo is from https://www.barnesandnoble.com/

Wright’s Coal Tar Soap, in business since the 1800s, is Hetty’s best description for Eustace’s scent. https://www.youtube.com/

The view from the hostel where Una and Ray stay may be like this one from the Ghyll Mill Hostel in North Yorkshire, within biking distance of where these girls live in Yorkshire. https://www.nationaltrail.co.uk/

Liselotte meets Carl outside King’s College in London. https://www.studyacrossthepond.com/

Liselotte lived with the Feldmans in Notting Hill, an area like this one: https://www.booking.com/