“Teacher, before we start we want to ask you a question….What does it mean to get into politics? How old do you have to be? Silence. The teacher stares, startled. Silence. The teacher hesitates before answering. Silence. Fuenzalida dreams of him, of the silence that settled over the classroom, which she can hear as clearly as our voices. Silence. No one says a thing, not a seat creaks, not a sheet of paper rustles. Boys and girls, says the math teacher, this is math class and you’re here to learn, not to talk nonsense.”—from a 7th grade classroom.

Bridging the gap between a novel and a novella, Space Invaders by Nona Fernandez is, in fact, as short as a novella, but it feels more like a much larger novel in the grandeur of its themes, its well-developed controlling ideas, the world-changing historical events which give it drama, and the intense, literary style which brings it all to life and makes it work. This powerful story takes place in Santiago de Chile during the time of Augusto Pinochet’s rise and military dictatorship, beginning in 1980 and extending to 1994 and later. The eight school children who are the main characters here, are ten years old as the novel opens – five boys and three girls who are close friends. Bright, curious, and observant, the children react to the very real conflicts around them, the military presence, and the sometimes bloody events which erupt and affect their lives as they grow up. For them, the drama is part of their “ordinary” lives, not unlike the wild afternoons they spend shooting little green bullets at the “Space Invaders” they are trying to conquer in their favorite computer game. It is the reader, of course, who recognizes through the changing points of view and the four-part division of the story line just how extraordinary these real events are.

Bridging the gap between a novel and a novella, Space Invaders by Nona Fernandez is, in fact, as short as a novella, but it feels more like a much larger novel in the grandeur of its themes, its well-developed controlling ideas, the world-changing historical events which give it drama, and the intense, literary style which brings it all to life and makes it work. This powerful story takes place in Santiago de Chile during the time of Augusto Pinochet’s rise and military dictatorship, beginning in 1980 and extending to 1994 and later. The eight school children who are the main characters here, are ten years old as the novel opens – five boys and three girls who are close friends. Bright, curious, and observant, the children react to the very real conflicts around them, the military presence, and the sometimes bloody events which erupt and affect their lives as they grow up. For them, the drama is part of their “ordinary” lives, not unlike the wild afternoons they spend shooting little green bullets at the “Space Invaders” they are trying to conquer in their favorite computer game. It is the reader, of course, who recognizes through the changing points of view and the four-part division of the story line just how extraordinary these real events are.

Section I, which contains eight short mini-chapters, alternates stories about the characters as young school children, beginning in 1980, and contrasts them with the children’s recollections more than ten years later. This allows the reader to see similar childhoods and events from various points of view from the outset of the story and observe the changes which time and events in Chile have wrought. The first tiny episode introduces a young girl, Estrella Gonzalez, as she is brought into her classroom by her father, who is in uniform. She kneels, respectfully, in front of the statue of the Virgen del Carmen and kisses her thumb. In the second episode, many years later, the group of seven other children who knew and liked this girl earlier, all share their memories of her, though each remembers her differently. Even in later years, Estrella Gonzalez, the former “new girl,” speaks to them individually in their dreams, and it soon becomes clear that Estrella actually left them many years ago and moved out of their lives but did not disappear. Maldonado, Estrella’s best friend, remembers receiving a letter from Estrella, back in the old days, where Estrella talks about a work accident her father has had and the fact that she has lost her little brother Rodrigo, only a year younger, though his death remains a mystery.

Episode V belongs to Riquelme, the only one of the children who ever goes to Estrella’s house, where they play Space Invaders for hours. Riquelme does not know how Estrella’s brother died, but, while visiting, Estrella’s father takes off his left hand. “It was a wooden hand, like the peg leg of a pirate. There was a black leather glove on it.” Estrella explains that her father lost his hand in heroic actions throwing a bomb out of the way of innocent people, and that he now collects additional prostheses in all possible materials to use when necessary. Riquelme, and everyone else, is afraid of the night-mare-inducing “spare hands” that have become part of her father’s “collection,” and no other child ever visits the house again. Another flashback in episode VII, features Zuniga who, each year is a “hero” in a pageant at school. This time, a glitch leads to an ending in which he appears instead as a coward. Estrella appears to him in a dream much later, to say that her brother drowned but no one knows how or why. “I know I’m dreaming but her voice in my ear is as real as the feather weight of the sheets on my body. It’s her,” Zuniga says.

Estrella’s “Uncle Claudio” is recognizable to her friends because he drives a red Chevy Chevette.

Dreams, memories, and imagination form our visions of the past here and become even more clearly defined as this story develops. Time flips back and forth and around throughout the short sections, yet the narrative develops dramatically and quickly. “Time isn’t straightforward,” the author says. “It mixes everything up…advances backward, retreats in reverse…” In Section Two, 1982, “The Second Life,” the children are now in the seventh grade. Two big national events have occurred: the former president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, who opposed Augusto Pinochet, “died of unexplained septic shock at a private clinic.” Not long after, the head of the Chilean intelligence agency shoots a union leader five times, then slits his throat. Without explanation, the story soon shifts to Maldonado who has received a letter from her best friend Estrella on an unstated date. Estrella is now in Germany, with “Uncle Claudio” as a bodyguard. Her father still has not recovered from his “accident,” and he has had more surgery. In the next episode, from an even earlier time, some of Maldonado’s friends become involved in distributing flyers secretly in front of the school regarding a march against Pinochet. They are seen, however, by Estrella Gonzalez’s bodyguard, “Uncle Claudio,” whom they recognize because he always drives a red Chevy Chevette. Episode V in “The Second Life” indicates that two of the twelve-year-old friends have been suspended from school for becoming involved in politics.

This large monument was erected in 2006 in memory of the three young Caro Degollados killed by national police.

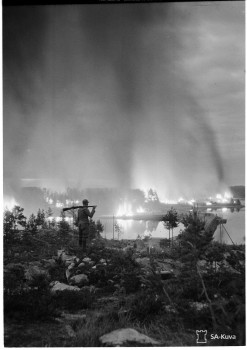

In the “Third Life” section, in 1985, two young men, described as “communist militants” barely in their twenties and not involved with the school group, are kidnapped, shot, and killed by national police. A third young “militant” has also been discovered with his throat slit. Now “coffins and funerals and wreaths were suddenly everywhere and there was no escaping them because it had all become something like a bad dream.” Members of the school group, including Maldonado, attend the public funerals for these Caro Degollados. Nine years later, in 1994, the officers who committed the crimes against these young communists are finally sentenced to life in prison. The group members recognize two of them. As author Nona Fernandez finishes this story in her clean, crisp prose, with her dreamy memories cropping up seemingly at random, she creates a dramatic, memorable, and important story of a time in Chile which she well remembers, as will the readers and lovers of literary fiction who discover this unusual book with its startling presentation.

Photos. The author’s photo appears in https://en.wikipedia.org

La Virgen del Carmen is honored by Estrella when she arrives at school on her first day. https://www.magicalandes.com

Estrella’s “Uncle Claudio” is easily recognized by her friends for the red Chevy Chevette that he drives. https://forums.vwvortex.com

Created in 2006, this monument honors the three young men, the Caro Degollados, killed by the national police. The school friends attended their funeral. http://www.serpajchile.cl

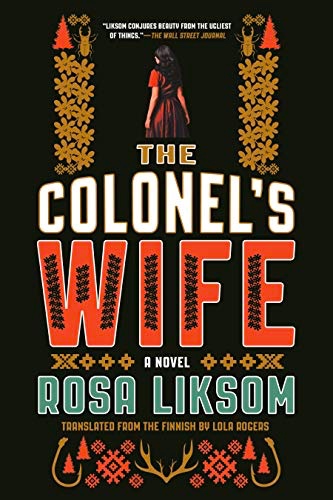

Author Rosa Liksom grew up in a Lapland village of eight houses, and she sets much of the action of this novel in Lapland as she creates, through flashbacks, the life story of an unnamed woman, now elderly, who is looking back on her life and her experiences in Finland during the tumultuous time during and after World War II.

Author Rosa Liksom grew up in a Lapland village of eight houses, and she sets much of the action of this novel in Lapland as she creates, through flashbacks, the life story of an unnamed woman, now elderly, who is looking back on her life and her experiences in Finland during the tumultuous time during and after World War II.

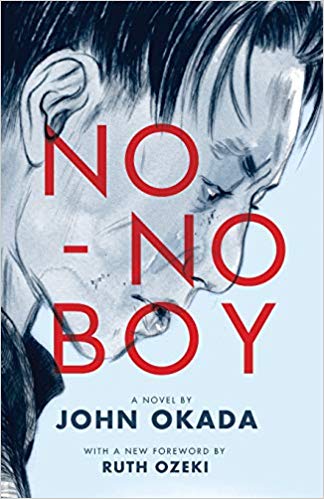

In this unique, ground-breaking novel, John Okada creates such a vibrant picture of the first- and second-generation Japanese-Americans during and immediately after World War II, that it is impossible to imagine readers of this book not being universally moved by what they read here.

In this unique, ground-breaking novel, John Okada creates such a vibrant picture of the first- and second-generation Japanese-Americans during and immediately after World War II, that it is impossible to imagine readers of this book not being universally moved by what they read here.

When French author Patrick Modiano won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014, the announcement came as a surprise to many American publishers since Modiano was almost unknown in the US at that time.

When French author Patrick Modiano won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014, the announcement came as a surprise to many American publishers since Modiano was almost unknown in the US at that time.