“[J. P.] Morgan must be embarrassed. He was a man who bought shipping lines and railroads as if they were curios and trinkets, but now the most perfect of all his prizes was adrift in the North Atlantic with half of New York aboard. It was as if he had invited friends for cocktails at his magnificent white-marble library and then set the place alight. It was worse than embarrassing. It was bad manners.”—John Steadman, reporter, on the fate of the Titanic.

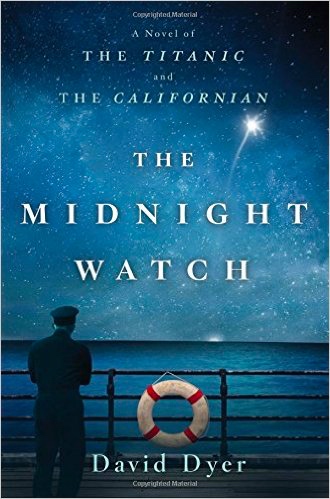

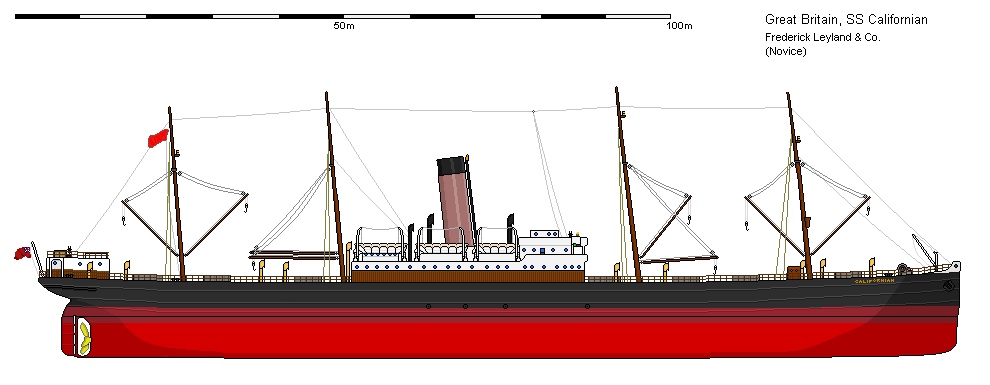

I grew up with stories of the Titanic, as did my sisters, and these stories have been part of my family life since the beginning. My mother was born the night the Titanic hit the iceberg – on April 14, 1912 – a fact imprinted on us from birth. Shortly after midnight that night, the Titanic sank with a loss of over fifteen hundred passengers. What this novel makes clear is something that is, in many ways, even more dramatic than the sinking of the Titanic itself: The Titanic was not alone at sea as it was sinking. There was another ship not ten miles away – the S.S. Californian – a ship which might have saved hundreds of passengers if it had gone to the rescue. The Californian’s crew saw the distress signals and the changes in the appearance of the Titanic’s on-deck lights, and though they informed the captain of what they saw, he never gave the order to go to the Titanic’s aid and never even came up to the bridge. This recently released “novel,” based on facts, is primarily the story of this ship, the Californian, its captain and crew, and why it never became the savior of some of the fifteen hundred people who died.

I grew up with stories of the Titanic, as did my sisters, and these stories have been part of my family life since the beginning. My mother was born the night the Titanic hit the iceberg – on April 14, 1912 – a fact imprinted on us from birth. Shortly after midnight that night, the Titanic sank with a loss of over fifteen hundred passengers. What this novel makes clear is something that is, in many ways, even more dramatic than the sinking of the Titanic itself: The Titanic was not alone at sea as it was sinking. There was another ship not ten miles away – the S.S. Californian – a ship which might have saved hundreds of passengers if it had gone to the rescue. The Californian’s crew saw the distress signals and the changes in the appearance of the Titanic’s on-deck lights, and though they informed the captain of what they saw, he never gave the order to go to the Titanic’s aid and never even came up to the bridge. This recently released “novel,” based on facts, is primarily the story of this ship, the Californian, its captain and crew, and why it never became the savior of some of the fifteen hundred people who died.

Author David Dyer, now a literature professor in Sydney, Australia, seems uniquely qualified to deal with many of the maritime and legal issues involved in the aftermath of the Titanic disaster. A graduate of the Australian Maritime College, he worked on merchant ships for years, later moving to London, where he was hired as a lawyer for the company whose parent firm represented the Titanic’s owners in 1912. With access to legal documents and artifacts which have previously had little attention, Dyer, fascinated with the Titanic’s story, could not stop thinking about why the Californian did not respond to distress signals, and his “novel” on this subject will, no doubt, fascinate both historians and readers who want to know more about what the Californian was doing while so many people who might have been saved, perished. Actual transcripts of the testimonies by the Californian’s officers at both a U. S. Senate committee investigation, held immediately after the sinking, and at a British legal inquiry within three weeks after the disaster add realism and insights into the characters and their possible motivations. The author then follows up years later by revisiting some of the key characters and noting what they did and said over the rest of their lives, indicating that the book represents “my best guess as to what actually happened during the Californian’s voyage and afterwards.”

For two-thirds of the novel, Dyer establishes a pattern in which he alternates the point of view between John Steadman, a reporter and feature writer for the Boston American, with that of the officers and crew on the Californian. Steadman specializes in stories about the bodies associated with various disasters, creating vivid images which appeal to his audience and allows them to understand the human and emotional issues involved. He has already reported in detail about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of March 25, 1911, in which 146 garment workers perished in a fire on the 8th– 10th floors of a building in Greenwich Village in which the stairwells and doors were locked to prevent people, mostly women in their early twenties, from taking unauthorized breaks. The Titanic disaster was an even greater abomination, with the lifeboats reserved for first class passengers, even including some men who took the places of women and children from other classes. Steadman even discovers that the U. S. Senate committee’s investigation of this disaster showed that not one person who was traveling third class was interviewed for the inquiry, and it appears that none were available because so few had survived.

The point of view of the Californian is represented primarily by Herbert Stone, the second officer, whose job involved the watch from midnight to 4:00 a.m., the time during which the Titanic sank. Cyril Evans, “the Marconi man,” responsible for all the radio telegraphy between the Californian and other ships in the area, including the Titanic, was in direct contact with the Titanic and with the Carpathia. Arriving two hours after the Titanic had already sunk, the Carpathia eventually rescued over seven hundred people from lifeboats, all people whom the Californian might have rescued much earlier if they had made the effort to go to the site. Though Evans later proves to be someone whose “memories” and point of view are changeable, Stone, who has seen eight distress flares, refuses to be silenced when an inquiry is opened. The captain slept through the emergency and later put pressure on his men to support him, and many of them co-operated.

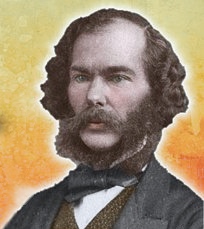

Capt. Stanley Lord, who never gave the order to rescue survivors from the Titanic. Photo by Senan Moloney.

Author Dyer presents the highly charged atmosphere and the horrors of the sinking of the Titanic after it hits the iceberg in realistic detail, then expands the trauma to include the Californian as potential saviors of the ship who failed in their human responsibilities, adding to the power of his narrative. He uses some of the testimony of the U. S. Senate inquiry to illustrate the elitism of some of the Californian’s officers and the willingness of some of them to mock the crew who were left alone on the ship to deal with the trauma of the Titanic as it sank, while the captain chose not to join them on the bridge. Those men, willing to do something but unable because of the limitations of their jobs and their obligations to their superiors, were also among the casualties as the Titanic sank. Some of them lived for dozens of years, consumed by guilt, especially about the toll of the children: As Steadman indicates to the wife of an officer, “There’d been barely a mention of the “children who died…You could read column after column about Mr. Astor or Mr. Guggenheim… but nothing about the children. There were fifty-three of them left behind…but no one seems to care much about them…or even know about them.” This novel reminds the reader of the full toll.

ALSO about the Titanic: EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF by Beryl Bainbridge

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on https://www.penguin.com.au

The photo of the sinking Titanic is part of an animated video of the disaster which may be found here: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

The model of the Californian is by Shipbucket: http://www.shipbucket.com Double-click to enlarge.

Captain Stanley Lord always refused responsibility for the Californian’s failure to attend the Titanic and rescue its passengers. Photo by Senan Moloney. https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org

Second officer Herbert Stone saw the Titanic’s distress signals and informed Captain Lord of those and of the changes in the appearance of the Titanic as it sank. http://www.theaustralian.com.au

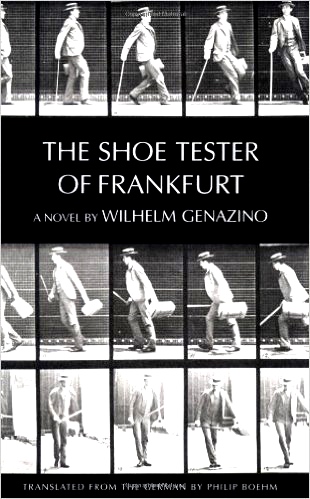

e this sensation that people like me should be told to either disappear or else get remodeled like the old buildings. This sensation is connected with another feeling I often have, namely that I’m here in this world without any inner authorization. Strictly speaking, I’m still waiting for someone to ask me whether I really want to be here. I imagine how nice it would be if I could grant myself this permission, let’s say this afternoon.” –Unnamed speaker, as he walks around Frankfurt.

e this sensation that people like me should be told to either disappear or else get remodeled like the old buildings. This sensation is connected with another feeling I often have, namely that I’m here in this world without any inner authorization. Strictly speaking, I’m still waiting for someone to ask me whether I really want to be here. I imagine how nice it would be if I could grant myself this permission, let’s say this afternoon.” –Unnamed speaker, as he walks around Frankfurt.

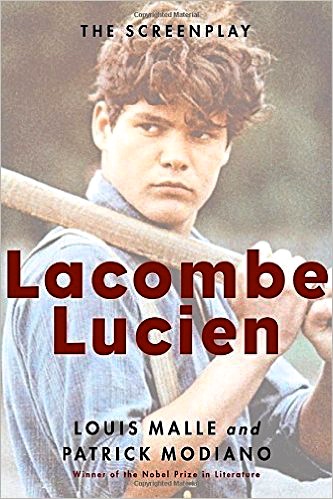

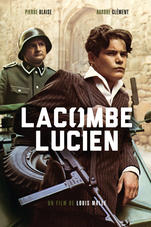

Produced and directed by famed cinematographer Louis Malle and written by Louis Malle and Patrick Modiano, who became the Nobel Prize for Literature winner in 2014, this 1974 film of Lacombe, Lucien broke some unspoken taboos when it was first shown. Only once before had a film raised questions about the masses of French citizens, many of them living in the countryside, who were ignorant or oblivious to the horrors of the Holocaust and the terrible costs to France at the hands of the Nazis in Vichy France. Marcel Ophuls had first produced a documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, in 1972, nearly thirty years after World War II ended, claiming that the prevailing view of the actions of the French citizenry during the war was naïve. Many citizens had been working farms in rural areas during the war and did not know or care to find out about what was happening on a national level – they had enough to worry about keeping food on the table and their families safe. A surprising number of citizens had collaborated with the Germans, not for political reasons, but because they believed that it was the only way they would be able to survive, and far fewer had worked with the Resistance to overthrow their German occupiers than was once believed. Ophuls suggested that most citizens just accepted what was happening because they did not believe they had much choice.

Produced and directed by famed cinematographer Louis Malle and written by Louis Malle and Patrick Modiano, who became the Nobel Prize for Literature winner in 2014, this 1974 film of Lacombe, Lucien broke some unspoken taboos when it was first shown. Only once before had a film raised questions about the masses of French citizens, many of them living in the countryside, who were ignorant or oblivious to the horrors of the Holocaust and the terrible costs to France at the hands of the Nazis in Vichy France. Marcel Ophuls had first produced a documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, in 1972, nearly thirty years after World War II ended, claiming that the prevailing view of the actions of the French citizenry during the war was naïve. Many citizens had been working farms in rural areas during the war and did not know or care to find out about what was happening on a national level – they had enough to worry about keeping food on the table and their families safe. A surprising number of citizens had collaborated with the Germans, not for political reasons, but because they believed that it was the only way they would be able to survive, and far fewer had worked with the Resistance to overthrow their German occupiers than was once believed. Ophuls suggested that most citizens just accepted what was happening because they did not believe they had much choice.

Delightful, playful, clever, and humorous, Spanish author Juan Gomez Barcena’s debut novel is also consummately literary, telling a story on several levels at once but doing so while maintaining the atmosphere of a college prank. Two university students who are also members of the moneyed elite in Lima, Peru, in 1904, are anxious to obtain the newest book of poetry written by Juan Ramon Jimenez, a much-admired twenty-four-year-old writer in Spain who has been publishing lyrical poetry to international acclaim. Though twenty-year-old Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez consider themselves poets, too, they have been writing to no acclaim; few others from their college find their work interesting or original. Poet Jimenez eventually goes on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956, while no one now remembers the names of Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez, except for their possible creation of a hoax regarding the world-famous poet Jimenez, the hoax described in this book.

Delightful, playful, clever, and humorous, Spanish author Juan Gomez Barcena’s debut novel is also consummately literary, telling a story on several levels at once but doing so while maintaining the atmosphere of a college prank. Two university students who are also members of the moneyed elite in Lima, Peru, in 1904, are anxious to obtain the newest book of poetry written by Juan Ramon Jimenez, a much-admired twenty-four-year-old writer in Spain who has been publishing lyrical poetry to international acclaim. Though twenty-year-old Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez consider themselves poets, too, they have been writing to no acclaim; few others from their college find their work interesting or original. Poet Jimenez eventually goes on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956, while no one now remembers the names of Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez, except for their possible creation of a hoax regarding the world-famous poet Jimenez, the hoax described in this book.

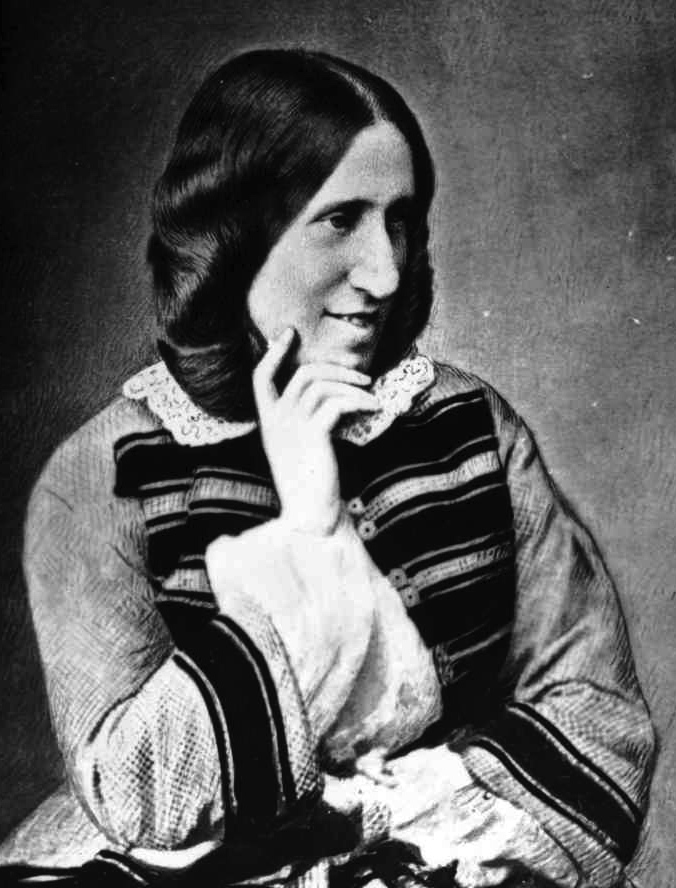

Marian Evans, the author known as George Eliot, is sixty years old as this biographical novel opens in June, 1880, and she is on the train to Venice for her honeymoon with new husband, John Walter Cross, a handsome young forty-year-old. Hiding her face behind a white lace mantilla so that she will not be pestered by fans of her books begging for autographs, she believes that the mantilla, “though not completely hiding her face…distracted from it, from her large nose and broad jaw, and she welcomed this because she believed that she was homely.” She had lived happily with philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes from 1854 until his death in 1878, and though she called herself Mrs. Lewes, they had never married. Lewes, already married, had an “open marriage” in which his wife ultimately had four children by another man, all of whom Lewes supported, and he was legally unable to get a divorce.

Marian Evans, the author known as George Eliot, is sixty years old as this biographical novel opens in June, 1880, and she is on the train to Venice for her honeymoon with new husband, John Walter Cross, a handsome young forty-year-old. Hiding her face behind a white lace mantilla so that she will not be pestered by fans of her books begging for autographs, she believes that the mantilla, “though not completely hiding her face…distracted from it, from her large nose and broad jaw, and she welcomed this because she believed that she was homely.” She had lived happily with philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes from 1854 until his death in 1878, and though she called herself Mrs. Lewes, they had never married. Lewes, already married, had an “open marriage” in which his wife ultimately had four children by another man, all of whom Lewes supported, and he was legally unable to get a divorce.