NOTE: WINNER of many European Prizes over the years, Patrick Modiano was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014.

“Every time I went to the movies, I took care to arrive after the newsreel. No, it was best to avoid knowing anything about the fate of the world. Best not to aggravate that fear, that feeling of imminent disaster. Concentrate on trivialities: fashion, literature, cinema, variety shows. Stretch out on the long deck chairs, close your eyes, and relax…Forget. Right?” – Victor Chmara, Villa Triste

French author and Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano has always claimed that his stories are not autobiographical, but his novels, themes, places, and details about life often repeat and attest to the ways in which his own dysfunctional childhood has had long-lasting effects on his life. Permanently alienated from his neglectful and uncaring parents, who essentially abandoned him when he was only ten, he grew up with no close family ties, no strong adult role models, and no sense of home or permanence, conditions he writes about with great sensitivity in Suspended Sentences (1988) and other novels. By the age of eighteen, having completed school, Modiano was on his own, but he succeeded in finding a mentor for his writing, novelist Raymond Queneau, and at age twenty-three, with Queneau’s help, he published his first novel. Two other successful novellas followed in 1968 and 1972, the three novellas now known collectively as “The Occupation Trilogy.” Villa Triste (1975), is the first novel written by Modiano after the success of these novellas.

French author and Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano has always claimed that his stories are not autobiographical, but his novels, themes, places, and details about life often repeat and attest to the ways in which his own dysfunctional childhood has had long-lasting effects on his life. Permanently alienated from his neglectful and uncaring parents, who essentially abandoned him when he was only ten, he grew up with no close family ties, no strong adult role models, and no sense of home or permanence, conditions he writes about with great sensitivity in Suspended Sentences (1988) and other novels. By the age of eighteen, having completed school, Modiano was on his own, but he succeeded in finding a mentor for his writing, novelist Raymond Queneau, and at age twenty-three, with Queneau’s help, he published his first novel. Two other successful novellas followed in 1968 and 1972, the three novellas now known collectively as “The Occupation Trilogy.” Villa Triste (1975), is the first novel written by Modiano after the success of these novellas.

Only thirty years old when Villa Triste hit the Parisian literary scene, Modiano reveals his continuing belief in “writing about what you know.” Here his main character betrays a palpable sense of loss, a lack of understanding about who he is and who he might become. A man alone, he yearns for deep, long-time relationships. Calling himself Victor Chmara, a name he tells us is invented, the main character in Villa Triste is eighteen as the novel opens in 1960, and Modiano’s development of the intimate details of his thinking and his emotional states attest to the powerful influence his own past must have had in the creation of this realistic character. Victor does not connect effectively with the rest of the world, and his uncertainty about how to deal with issues of life, love, and the ghosts of his past lead to his pervasive loneliness and sense of isolation. As he reveals in the quotation which begins this review, he avoids the big issues, keeping himself moving, living in the moment, and losing himself in films, books, and romantic attachments – anything to avoid thinking about the uncertainties of French life, which add to his own tensions.

For the past six years, the French have been fighting the Algerians, who are struggling for independence, and news reports suggest that the struggle is about to become a full-fledged war. At eighteen, Victor is terrified of being drafted, fearful of losing the life which he has never really had a chance to explore, and this may be the reason that he is using a false name, and eventually pretending to be a Russian count. He changes his place of residence frequently, having somehow acquired enough money to pay for his stays in small hotels and for his food and entertainment. As this novel opens, Victor is living in a French “spa resort” on the shore of a lake, a place he regards as a “refuge because it was [only] five kilometers from the Swiss border. At the first sign of danger,” he thinks, “all I [have] to do [is] cross the lake.” On his first night at his new residence, he takes a walk, stopping to enjoy the changing colors of a fountain outside the casino, where he’d “go off in a dream, taking mechanical sips of my drink.” As it is mid-June, the “season” has started, with parties, dinners, theatrical productions, ballets, boat trips, films, celebrity appearances, and trips to the casino. A night-time walk back to his residence one night is so sensuous that he begins to lose his fear, asking, “Who would have ever thought of coming to look for me among these distinguished summer vacationers?”

Martine Carroll (1920 – 1967), whom Yvonne resembled. Photo by Lucienne Chevert

Before long Victor has met Yvonne, a gorgeous woman in her early twenties – “Auburn hair. Green shantung dress. And the stiletto-heeled shoes women wore.” She has already had a small part in a film and hopes to make connections that will improve her chances of making more. She introduces him to “Doctor” Rene Meinthe, a gay man in his forties with whom she seems to be traveling and who wants to help her with her career. Meinthe, who adds Chmara to his retinue of unusual friends, makes many mysterious side trips to other cities, which often leave him so agitated upon his return that he suffers from tics. No one know where he goes or why. Though Victor also meets other denizens of the Haute-Savoie during that “season,” it is Yvonne, the young actress who “resembles Martine Carroll,” who most fascinates him, and he quickly moves into the Hermitage with her.

If you are wondering when the action is going to start, you are looking in the wrong place. The “action” here is internal action, related from the point of view of Victor. Most of the outside action is superficial, deliberately so, a way for the wealthy and would-be wealthy to avoid thinking about their own problems and the problems of the country. One event which consumes Meinthe and Yvonne is the Houligant Cup which is the prize in a “sort of concours d’elegance,” or contest of elegance. You had to own a luxury automobile to participate in the parade, and the objective was to show from your appearance and behavior how “elegant” you were. Meinthe decides this would be a great career move for Yvonne, if they can win. Their biggest problem is whether his Dodge convertible is elegant enough for the parade.

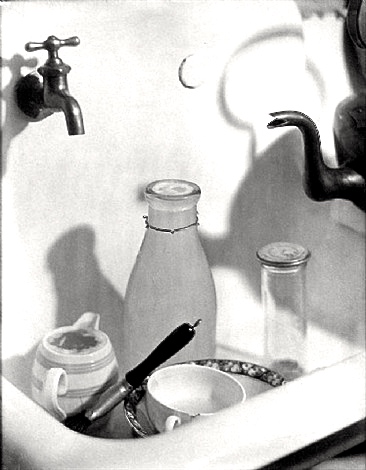

Sitting outside a casino with a fountain of many colors inspires Chmara to put his fear aside, going “off into a dream” while sipping his drink.

With concerns like these, the reader must be patient with young Chmara as he sorts out his life. Some of his questions never do get answered, and others seem to open doors to new questions. Modiano broadens his perspective at the halfway point of the novel, jumping forward twelve years to rejoin some of the characters as they revisit this place where they escaped the world briefly, then jumping back to expand on life in 1960. In some cases, Chmara finds out much more about his friends, even visiting the places where they grew up – Villa Triste, in the case of Meinthe – and meeting family, in one case. In others, he never does find out what he wants to know. Emphasizing the ways people deal with life or try to escape it, and the ways they remember the events which are important to them at the time they live through them, Modiano presents a new way of examining the past and its importance. This light novel hides some big truths within its superficialities.

Also: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, HONEYMOON, FAMILY RECORD, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (with Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay, LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE, PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

(Note: Those who have never read Modiano would do well to begin with SUSPENDED SENTENCES, a book which sets the scene for many of his other books.)

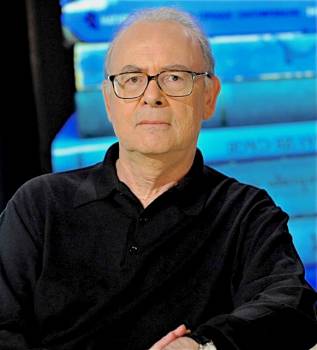

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.europe1.fr/

Martin Evans’s book about the war between Algeria and France is available on Amazon. http://www.amazon.com/

The photo of Martine Carroll (1920 – 1967), by Lucienne Chevert, is from http://filmstarpostcards.blogspot.co

The Dodge Kingsway Convertible which Meinthe and Yvonne used in the Houligant Cup may be found on http://details-of-cars.com

A fountain which changes colors, outside the casino, helps Chmara to lose his sense of fear. http://honeymoons.about.com

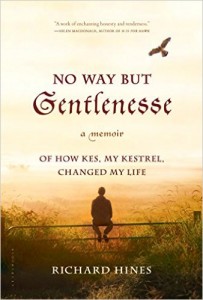

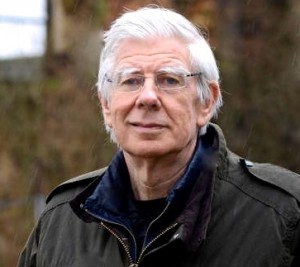

In this memoir of a man’s life, from his problematic childhood in the rural south Yorkshire mining village of Hoyland Common in the late 1950s, through his current, highly successful adulthood in Sheffield, also in South Yorkshire, author Richard Hines, like Nicholas Cox in the quotation (above), makes total connection with his reader in ‘gentle and familiar’ ways. Rarely, if ever, have I had such a feeling of intimacy with an author as he tells about his life and draws me in completely. The key to his whole life took place when he was just fifteen – the summer that he “manned” a kestrel, a small hawk. In a kind of reversal from what the reader might expect of someone who ultimately trained several more raptors, Hines conveys a feeling, not of his own power and strength, but of earnestness and real vulnerability. Here Hines trusts the reader and opens his heart, just as the kestrels he trained seem to trust and yield to him, as long as he “[kept] his side of the bargain to provide [them] with food and fly [them] free in the fields.” Ultimately, the author, having entertained and captivated the reader throughout the book, moves on in the conclusion, leaving in his wake many readers who have “lived” his life with him and found their own lives enlarged by their contact.

In this memoir of a man’s life, from his problematic childhood in the rural south Yorkshire mining village of Hoyland Common in the late 1950s, through his current, highly successful adulthood in Sheffield, also in South Yorkshire, author Richard Hines, like Nicholas Cox in the quotation (above), makes total connection with his reader in ‘gentle and familiar’ ways. Rarely, if ever, have I had such a feeling of intimacy with an author as he tells about his life and draws me in completely. The key to his whole life took place when he was just fifteen – the summer that he “manned” a kestrel, a small hawk. In a kind of reversal from what the reader might expect of someone who ultimately trained several more raptors, Hines conveys a feeling, not of his own power and strength, but of earnestness and real vulnerability. Here Hines trusts the reader and opens his heart, just as the kestrels he trained seem to trust and yield to him, as long as he “[kept] his side of the bargain to provide [them] with food and fly [them] free in the fields.” Ultimately, the author, having entertained and captivated the reader throughout the book, moves on in the conclusion, leaving in his wake many readers who have “lived” his life with him and found their own lives enlarged by their contact.

“On October 27, 1949, at Orly, Air France’s F-BAZN is waiting to receive thirty-seven passengers departing for the United States…[including] Marcel Cerdan… former middleweight boxing champion… and the violin virtuoso Ginette Neveu…. The tabloid France-soir organizes an impromptu photo session in the departure lounge. In the first snapshot, Jean Neveu, Ginette’s brother, [is] smiling at her, while Marcel holds her Stradivarius and Ginette grins across at him.”

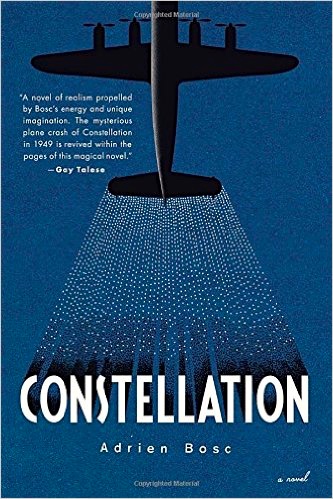

“On October 27, 1949, at Orly, Air France’s F-BAZN is waiting to receive thirty-seven passengers departing for the United States…[including] Marcel Cerdan… former middleweight boxing champion… and the violin virtuoso Ginette Neveu…. The tabloid France-soir organizes an impromptu photo session in the departure lounge. In the first snapshot, Jean Neveu, Ginette’s brother, [is] smiling at her, while Marcel holds her Stradivarius and Ginette grins across at him.” The plane takes off but never arrives in New York – nor does it arrive at the island of Santa Maria in the Azores, where the pilot had planned to refuel for the trip across the Atlantic. All thirty-eight passengers and eleven crew died when the plane crashed into a mountain top fifty-five miles from the airport at Santa Maria. French author Adrien Bosc wastes no time getting into the action of this book, which he calls a novel, though this “novel” is based on real life events and the historical record and feels more like a long piece of journalism or investigative reporting. There is almost no dialogue, something which even “fictionalized biographies” include, and the author interjects himself into the book and speaks directly to the reader, at times, when he is puzzled about the facts as he is uncovering them. Parts of the book feel like a quest story – in this case, the author’s quest for the complete truth about the crash and the fates of all the passengers. Certainly some of the “facts” here are extrapolations which the author himself makes from what he knows, and in that sense the book might qualify as a novel, but most readers will find themselves learning about the crash and its victims, rather than reliving it as one does in pure fiction.

The plane takes off but never arrives in New York – nor does it arrive at the island of Santa Maria in the Azores, where the pilot had planned to refuel for the trip across the Atlantic. All thirty-eight passengers and eleven crew died when the plane crashed into a mountain top fifty-five miles from the airport at Santa Maria. French author Adrien Bosc wastes no time getting into the action of this book, which he calls a novel, though this “novel” is based on real life events and the historical record and feels more like a long piece of journalism or investigative reporting. There is almost no dialogue, something which even “fictionalized biographies” include, and the author interjects himself into the book and speaks directly to the reader, at times, when he is puzzled about the facts as he is uncovering them. Parts of the book feel like a quest story – in this case, the author’s quest for the complete truth about the crash and the fates of all the passengers. Certainly some of the “facts” here are extrapolations which the author himself makes from what he knows, and in that sense the book might qualify as a novel, but most readers will find themselves learning about the crash and its victims, rather than reliving it as one does in pure fiction.

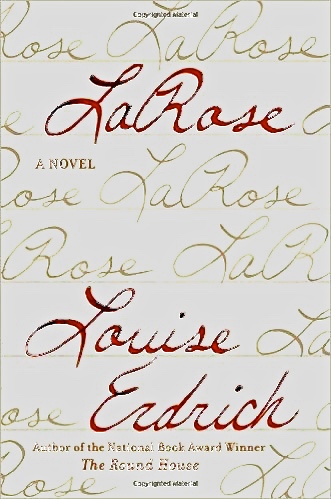

Within the first two paragraphs of this dramatic and incisive study of human relationships, author Louise Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians, introduces a series of powerful conflicts which pit family against family, culture against culture, and generation against generation. In the opening scene, quoted at the top of the review, Landreaux Iron, a careful and respected member of his culture, accidentally kills Dusty Ravich, the five-year-old son of Peter Ravich, a friend and family member with whom he had planned to share the meat from the buck. Racing back to Peter’s house, Landreaux encounters Peter’s wife Nola, who becomes understandably hysterical, and by the time the tribal police, the county coroner, and the state coroner have arrived, the trauma has been felt by all the members of both devastated families.

Within the first two paragraphs of this dramatic and incisive study of human relationships, author Louise Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians, introduces a series of powerful conflicts which pit family against family, culture against culture, and generation against generation. In the opening scene, quoted at the top of the review, Landreaux Iron, a careful and respected member of his culture, accidentally kills Dusty Ravich, the five-year-old son of Peter Ravich, a friend and family member with whom he had planned to share the meat from the buck. Racing back to Peter’s house, Landreaux encounters Peter’s wife Nola, who becomes understandably hysterical, and by the time the tribal police, the county coroner, and the state coroner have arrived, the trauma has been felt by all the members of both devastated families.

On the surface, The Illuminations, the fifth novel by Scottish author Andrew O’Hagan, appears to be a simple story about Captain Luke Campbell, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, and his grandmother, Anne Quirk, with whom he has always been particularly close. Luke has returned from the fighting with issues which prevent him from becoming close to those around him, perhaps reflecting some aspects of PTSD. His beloved grandmother Anne, now eighty-two, is staying at a co-operative living facility on the west coast of Scotland, where the other residents and a caring staff are trying to keep her from harm as her developing dementia begins to become dangerous. A former art photographer, whose work has recently interested a group which hopes to present a retrospective showing, Anne spent time in Canada, New York, Glasgow, and eventually Blackpool, before she mysteriously stopped doing any photography in 1963 when she was in her early thirties. Luke, whose mother Alice’s issues have always prevented her from becoming personally “engaged” with him, has come to Scotland after the war to try to help Anne. His father, Sean Campbell, also a soldier, died in the British fighting against the IRA in Northern Ireland many years ago,

On the surface, The Illuminations, the fifth novel by Scottish author Andrew O’Hagan, appears to be a simple story about Captain Luke Campbell, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, and his grandmother, Anne Quirk, with whom he has always been particularly close. Luke has returned from the fighting with issues which prevent him from becoming close to those around him, perhaps reflecting some aspects of PTSD. His beloved grandmother Anne, now eighty-two, is staying at a co-operative living facility on the west coast of Scotland, where the other residents and a caring staff are trying to keep her from harm as her developing dementia begins to become dangerous. A former art photographer, whose work has recently interested a group which hopes to present a retrospective showing, Anne spent time in Canada, New York, Glasgow, and eventually Blackpool, before she mysteriously stopped doing any photography in 1963 when she was in her early thirties. Luke, whose mother Alice’s issues have always prevented her from becoming personally “engaged” with him, has come to Scotland after the war to try to help Anne. His father, Sean Campbell, also a soldier, died in the British fighting against the IRA in Northern Ireland many years ago,