Note: Richard Wagamese was WINNER of Canada’s National Aboriginal Achievement Award for 2012.

“Jimmy said Starlight was the name given to them that got teachin’s from Star People. Long ago. Way back. Legend goes that they came outta the stars on a night like this. Clear night. Sat with the people and told ’em stuff. Stories mostly, about the way of things…Our people. Starlights. We’re meant to be teachers and storytellers. They say nights like this bring them teachin’s and stories back and that’s when they oughta be passed on again.”—Eldon Starlight, the father

On a magnificent, clear night, perfect for passing on stories about people and their heritage, Franklin Starlight, age sixteen, and his father Eldon, from whom he has been estranged for nearly all of his life, sit smoking around a campfire in the mountains, as their stories, often sad, emerge to be shared. Eldon, an alcoholic who is just days away from death, has persuaded his son-in-name-only to accompany him on his final trip “beyond the ridge.” Riding Franklin’s horse, to which he eventually needs to be tied hand and foot as he sinks in and out of consciousness, Eldon shares his life story, and stories involving other people around him, in a final effort to connect with his son and to reconcile himself with his own guilt about actions that have haunted his past. Young Franklin has been brought up by “the old man,” a white man, no kin, who has devoted his life to him, while Eldon Starlight, his real father, has lived many miles away and avoided all sense of responsibility since Franklin’s birth, losing himself in drink instead. The old white man has taught Franklin everything he knows – about being resourceful on the farm, thoughtful toward others, respectful toward the land and its animals, and resolute in his actions – the Indian way – and, unlike the disengaged Eldon Starlight, the boy and the old man love and honor each other through their actions.

On a magnificent, clear night, perfect for passing on stories about people and their heritage, Franklin Starlight, age sixteen, and his father Eldon, from whom he has been estranged for nearly all of his life, sit smoking around a campfire in the mountains, as their stories, often sad, emerge to be shared. Eldon, an alcoholic who is just days away from death, has persuaded his son-in-name-only to accompany him on his final trip “beyond the ridge.” Riding Franklin’s horse, to which he eventually needs to be tied hand and foot as he sinks in and out of consciousness, Eldon shares his life story, and stories involving other people around him, in a final effort to connect with his son and to reconcile himself with his own guilt about actions that have haunted his past. Young Franklin has been brought up by “the old man,” a white man, no kin, who has devoted his life to him, while Eldon Starlight, his real father, has lived many miles away and avoided all sense of responsibility since Franklin’s birth, losing himself in drink instead. The old white man has taught Franklin everything he knows – about being resourceful on the farm, thoughtful toward others, respectful toward the land and its animals, and resolute in his actions – the Indian way – and, unlike the disengaged Eldon Starlight, the boy and the old man love and honor each other through their actions.

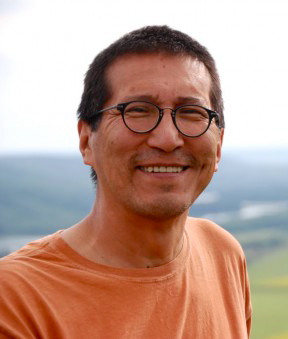

The novel that Ojibway author and storyteller Richard Wagamese creates from this outline is thoughtful and full of heart – and so gripping that it is hard to imagine any reader not being left breathless from the sheer drama of the writing and its overwhelming message. It is a wondrous novel about stories, their importance in our lives and memories, their ability to help us reconcile the past with the present, and ultimately their power to teach us the nature of the world and our relationship to it. Without didacticism or preachiness, Wagamese depicts the last few days in the life of Eldon Starlight whose stories lead to an unusual coming-of-age for son Franklin – at the same time that they may be a uniquely life-affirming experience for his irresponsible father. Stories about the natural beauty on the mountain and their respect for it accompany Franklin’s always-successful search for food as he leads his father “over the ridge.” Stories about Eldon’s past, including his relationship with Franklin’s mother, also emerge as Eldon tries to cope with the terrible aftereffects of the Korean War and his life afterward.

Eldon Starlight’s best friend Jimmy Weaseltail is his constant companion from the age of thirteen, when Eldon’s own father dies and Eldon has to drop out of school and to work with fruit pickers, wood cutters, fish gutters, and tree planters. After work, he and Jimmy both love to listen to Eldon’s mother read to them – Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Robert Louis Stevenson – authors from whom they get most of their “book learning” when their formal schooling ends early. Ultimately, Eldon and Jimmy work as “boom men,” helping to guide dangerous flotillas of logs down the river during logging season. Later, when Eldon and Jimmy sense that it is time to move on, they sign up for a Royal Canadian regiment. After training across the country at Camp Petawawa, they head for the Korean War and their own battles at Pusan, a turning point for both of them.

Since the reader already knows the outcome of Eldon’s death journey from the earliest pages of the novel, Wagamese performs an almost magical feat of keeping the reader intensely interested in the characters and their lives through the creation of parallel narratives. These unpretentious and straightforward stories carry the novel in several different directions simultaneously. The author focuses on five separate life-lines: The on-going life story of Eldon Starlight, Franklin’s father, in the days leading up to their final journey; Franklin’s early life as a child growing up on a farm with his white foster father, who has tried to teach him all the Indian lore he knows; the day-to-day story of Franklin and Eldon as they journey through the mountains to Eldon’s chosen resting place, absorbing the lessons nature has to offer along the way; the experiences of Eldon and Jimmy in Pusan during the Korean War; and ultimately, Eldon’s life after the war and his first connection with Franklin’s mother. Wagamese keeps all five plot lines moving forward smoothly without confusing the reader, at the same time that he withholds key information to develop considerable, on-going suspense about immediate outcomes.

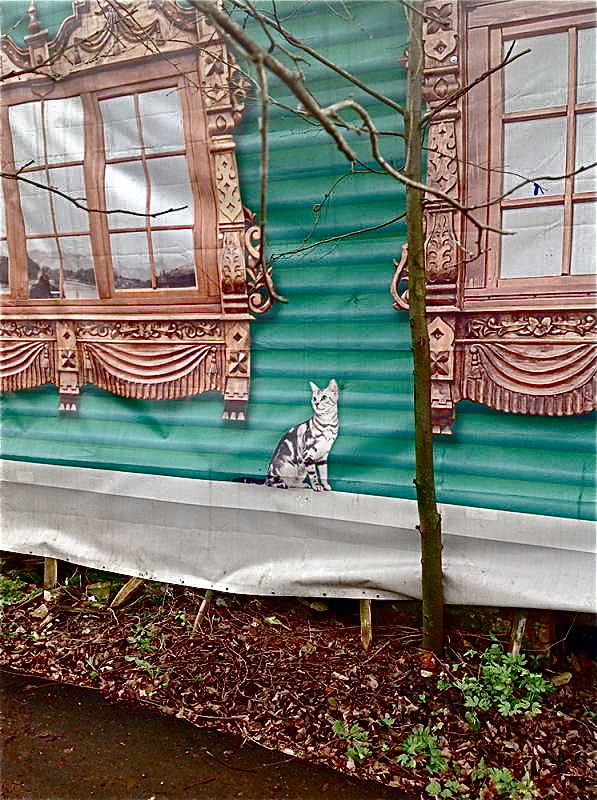

Photo by C. J. Foxcroft, showing a nine-foot grizzly, relative to the size of an average man. Franklin must deal with a grizzly by himself during his journey.

In unaffected and straightforward language, Wagamese draws the reader into the lives of Franklin and his father Eldon, both lives quite different from what most readers have experienced, yet we feel involved and caring because of the universal values which Wagamese clearly believes unite us all. At the same time, he also describes specifically Indian ways of life for Franklin, who “hears symphonies in wind across a ridge and arias in the screech of hawks and eagles, the huff of grizzlies and the pierce of a wolf call against the unblinking eye of the moon. He was Indian.” In riding to meet his father, forty miles away, he tells us that his horse “knew the smell of cougar and bear so he was content to let her walk while he sat and smoked and watched the land.” His descriptions of catching trout without a fishing rod, and thanking nature for its bounty, are balanced by irony when he first sees his father, “his buttocks like small lumps of dough and the rest of him all juts and pokes and seams of bone under sallow skin.” Ultimately, as Franklin accompanies the horse carrying his father through the mountains, he tells his father something he learned from “the old man”: “Everything a guy would need is here if you want it and know how to look for it…You gotta spend time gatherin’ what you need. What you need to keep you strong. He called it a medicine walk,” to which his unredeemed father comments, blandly, “Hand us that crock.”

A novel which satisfies on every level, Medicine Walk does honor to its author and to the culture he is describing at the same time that he is brutally honest. A magnificent novel – one of the best of the year.

ALSO by Wagamese: STARLIGHT and INDIAN HORSE

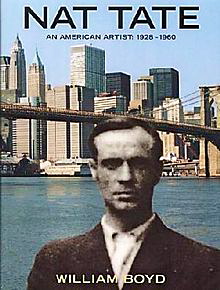

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://lakefieldliteraryfestival.com

The painting of a “boom man” may be found here: http://tim-ber.blogspot.com/

The horrors of the Korean War are seen in this iconic photo from https://en.wikipedia.org/

C. J. Foxcroft’s photo of a nine-foot grizzly bear, relative to the height of an average man, is from https://www.pinterest.com

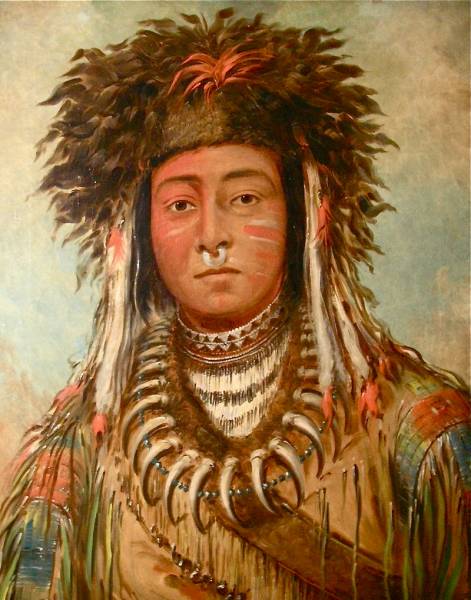

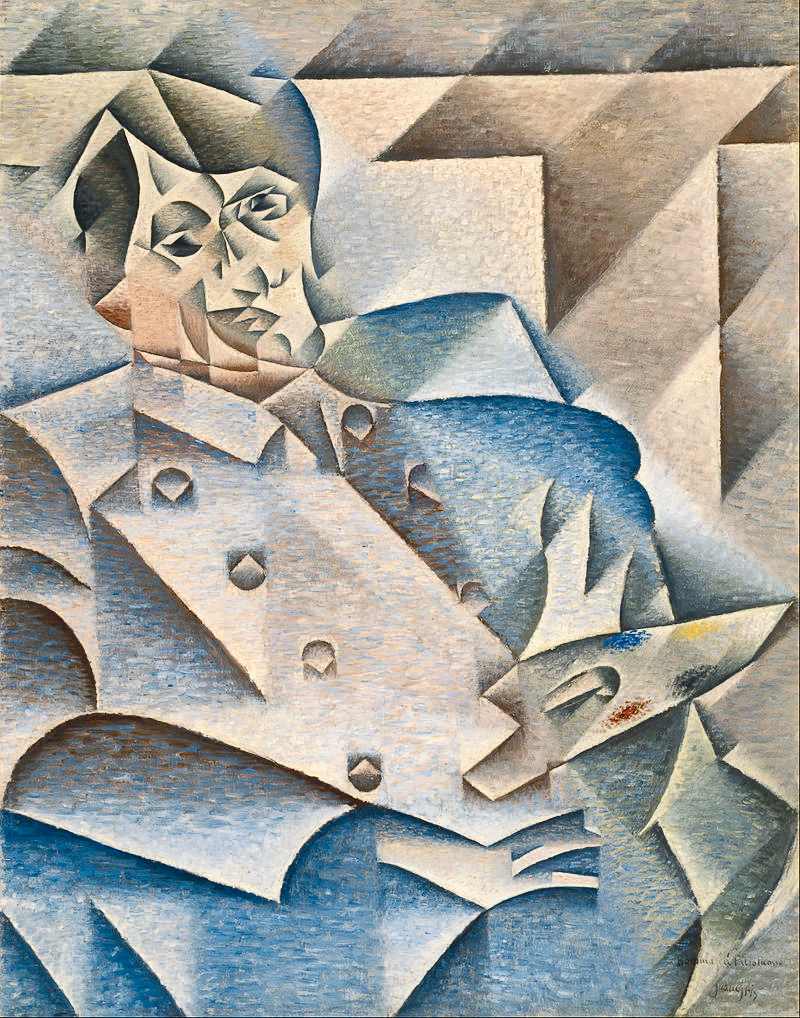

George Catlin painted a portrait of an Ojibway “Boy Chief” in 1843. It is part of the Mellon Collection. https://en.wikipedia.org/