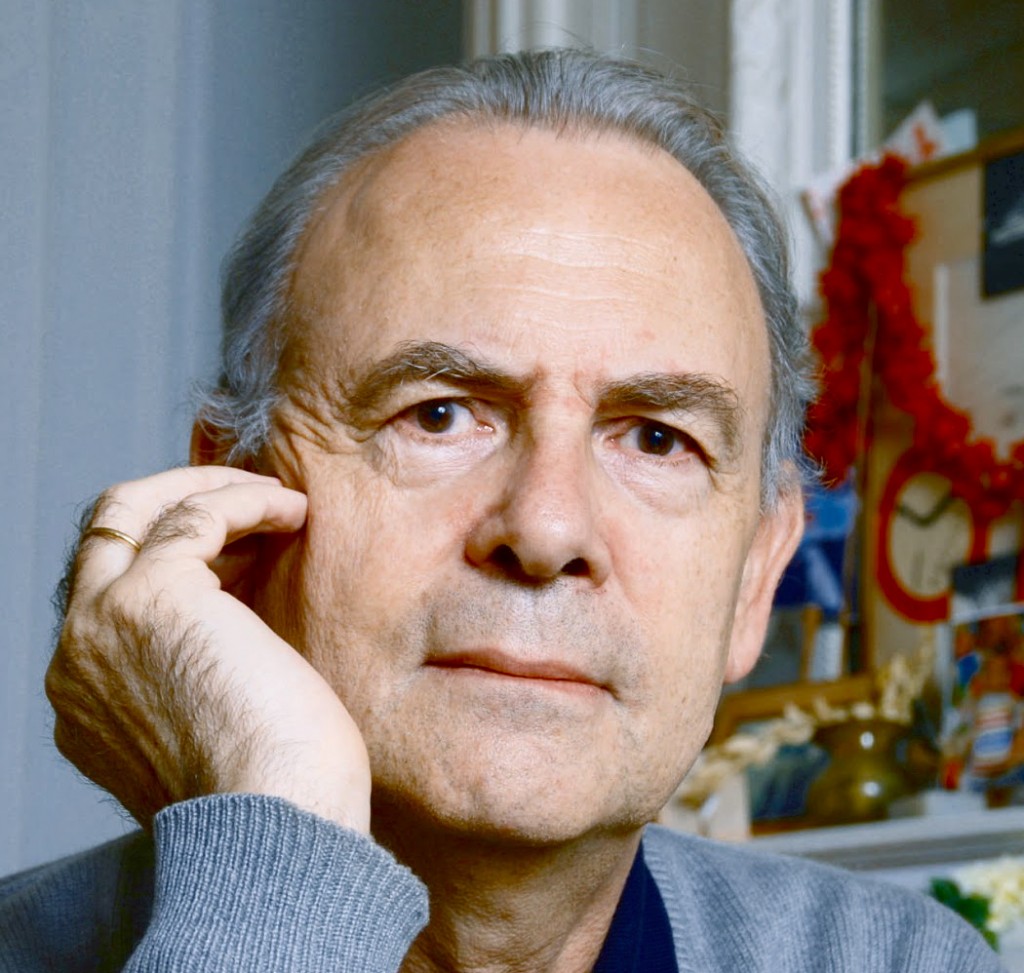

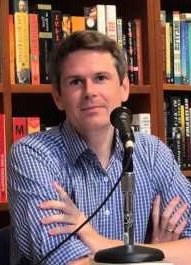

Note: French author Patrick Modiano was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014. His selection came as such a surprise that there were almost no copies of his novels available in English at the time of his win, a situation which has now been corrected. This new translation by Mark Polizzotti is published by Yale University Press.

“Apart from my brother, Rudy, his death, I don’t believe that anything I’ll relate here truly matters to me. I’m writing these pages the way one compiles a report or resume, as documentation, and to have done with a life that wasn’t my own….I have nothing to confess or elucidate and I have no interest in soul-searching or self-reflection….I lived through [these] events up to the age of twenty-one, as if against a transparency – like in a cinematic process shot, when landscapes slide by in the background while the actors stand in place on a soundstage.”

In this unusual approach to memoir writing, Patrick Modiano (1945 – present) does exactly what he says he will do in the quotation above, presenting all aspects of his life from his earliest memories until he turns twenty-one, without embroidering them, without drawing conclusions about who he is as a result of them, and without moralizing, excusing, or apologizing. It is as complete a record of his life as he can apparently remember or resurrect from records, with numerous references to people and places that were important to him but that most American readers will not recognize. The result feels more like an objective research tool for students of Modiano’s work rather than what one finds in memoirs written by other, more loquacious, authors. Though Modiano insists that his novels are fiction, his autobiographical details sometimes work their way into his stories and provide verisimilitude.

In this unusual approach to memoir writing, Patrick Modiano (1945 – present) does exactly what he says he will do in the quotation above, presenting all aspects of his life from his earliest memories until he turns twenty-one, without embroidering them, without drawing conclusions about who he is as a result of them, and without moralizing, excusing, or apologizing. It is as complete a record of his life as he can apparently remember or resurrect from records, with numerous references to people and places that were important to him but that most American readers will not recognize. The result feels more like an objective research tool for students of Modiano’s work rather than what one finds in memoirs written by other, more loquacious, authors. Though Modiano insists that his novels are fiction, his autobiographical details sometimes work their way into his stories and provide verisimilitude.

Those who have read a novel like Suspended Sentences, for example, cannot help but believe that much, if not most, of that novel is autobiographical. Here in this memoir, however, Modiano gives only the basic outlines of the events at the heart of that novel, and one must believe that the action in this and other novels has been embellished, developed, and described in ways which make for great fiction, whether or not it is completely true. At age twenty-one, Modiano tells us in the conclusion, he leaves his childhood and early life behind. His break with his family and the acceptance of his first book for publication inspire him to “set sail before the worm-eaten wharf [can] collapse.” “La Place de L’Etoile,” his novella published in 1968, gives him his sails: It is winner of both the Prix Feneon and the Roger Nimier Prize.

Modiano’s great-grandfather, a Flemish dockworker, served as the model for this statue by Constantin Meunier, located in the main square in Antwerp

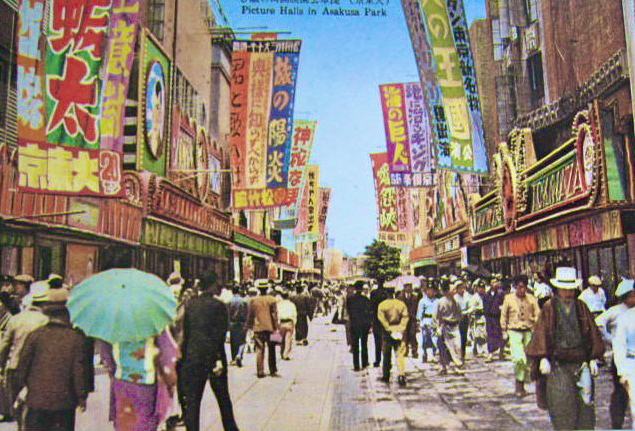

As the author tells us at the beginning of this memoir, his paternal grandfather and his father were both Jewish, a fact that seemed to make little difference in his father’s under-the-radar existence during the Occupation and life in post-war France. His mother, the daughter of a hard-working dockworker, was Flemish. A chorus girl and actress, she was described by her son as “a pretty girl with an arid heart.” When a fiancé gave her a chow-chow dog, at one point, “she didn’t take care of it and left it with various people, as she would later do with me.” The chow-chow eventually killed itself by leaping from a window, a result which the author admits “touches me deeply…I feel a great kinship with him.” (He later illustrates his memoir’s title by describing himself as “a dog who pretends to have a pedigree.”) His father, who haunted the lower class theatres where he met Patrick’s mother, enjoyed underworld connections, making his living by smuggling petroleum into Paris for sale and other black market activities, from which he sometimes had to escape to live with others to avoid arrest. Eventually, he spent time in Mexico, Canada, Guyana, Equatorial Africa, and Colombia engaged in “business.”

Both parents ignored and often farmed out Patrick, born in 1945, and his younger brother Rudy to caretakers, maintaining little, if any, contact with them. At one point, the two boys, ages four and one, spent two full years with caretakers in Biarritz, with no parental visits. Later, he occasionally saw his father, but of his mother, he says, “I cannot recall a single act of genuine warmth or protectiveness from her.” He skims over his early life with caretaker Suzanne Bouquerau and other circus people, who lived near an old chateau, both of which feature in Suspended Sentences, providing little additional detail in the memoir, saying only that Suzanne was arrested for burglary, at which point Modiano was reclaimed by his father. At age eleven, Modiano began attending boarding schools, a way of life which did not change during the rest of his education. Modiano’s brother Rudy died a year after Modiano began boarding school, an event which was so traumatic for the author that he says, “Apart from my brother, Rudy, his death, I don’t believe that anything I’ll relate here truly matters to me.” End of subject, no details.

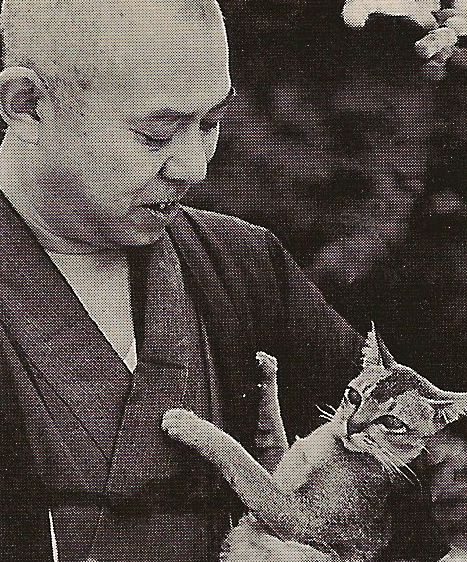

Modiano’s stepmother, “the ersatz Mylene Demongeot,” supposedly resembled this famous French actress.

Eventually his parents divorced, and his father married a woman Modiano always refers to as the “ersatz Mylene Demongeot” because she resembled a popular actress. She was even less interested in Patrick than his mother, doing everything possible to keep her husband from having to deal with the responsibilities, especially financial, of parenthood. Modiano’s late teen years are as traumatic as one would expect for a neglected teen, as he becomes more and more challenging and resentful of his father. He chooses to live with his now impoverished mother, though they have no real source of income. The “ersatz Mylene” takes it upon herself to interfere when Modiano goes to his father, desperate for money, and she persuades his father to press charges against his son.

In 1962, Modiano’s father enrolled him at the Lycee Henri IV as a full boarder, though his parents lived only a few hundred yards from the school, inspiring a crisis and a new stand by Modiano.

Somehow Modiano survives both of his parents and his “ersatz” stepmother, keeping himself intellectually alive through his contacts with, among others, Boris Vian, Joseph Roth, and eventually Raymond Queneau, who invites him to visit him on Saturdays, occasions in which Modiano, almost twenty-one, discusses the book he is writing and gets advice. As the memoir winds down and his twenty-first birthday gets closer, Modiano starts summing up his life, confessing to some petty crimes and what he did, on his own, to make amends. When his a novella called “La Place de L’Etoile” is accepted for publication, Modiano tells us, he gets ready to “set sail before the worm-eaten wharf can collapse” and when he does, he draws a curtain across that early part of his life, at least emotionally, revisiting it, apparently, only when he wants to use those life experiences in a fictional sense. Having survived and triumphed, he is now solely in charge of his new life.

ALSO by Modiano: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, FAMILY RECORD, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (with Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay, LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://revistadiners.com.co/

Modiano’s Belgian grandfather posed for “The Dockworker,” a statue by Constantin Meunier, located in the main square of Antwerp. http://flickrhivemind.net/

The author’s actress mother had a bit part in “Rendez-vous in July,” a French comedy from 1949. It was nominated for the Grand Prize in the Cannes Film Festival. http://www.imdb.com/

Modiano’s stepmother, “the ersatz Mylene Demongeot,” supposedly looked like her namesake, this popular French actress. http://en.unifrance.org

When Modiano’s father enrolled him as a full boarding student at the Lycee Henri IV, though the father, mother, and stepmother all lived only a few hundred yards from the school, Modiano rebelled. He had been living in dorms for the past six years, and he had had enough. http://www.lefigaro.fr

ARC: Yale University Press