“July is the fireworks season. A whole world, on the brink of extinction, was sending up one last flurry of sparks beneath the foliage and the paper lanterns. People jostled each other, they spoke in loud voices, laughed, pinched each other nervously. You could hear glasses breaking, car doors slamming. The exodus was beginning…Smoke rises from the chimneys: people are burning their old papers before absconding. They don’t want to be weighed down by useless baggage.”—Paris, as the Occupation begins in earnest, 1940, from The Night Watch.

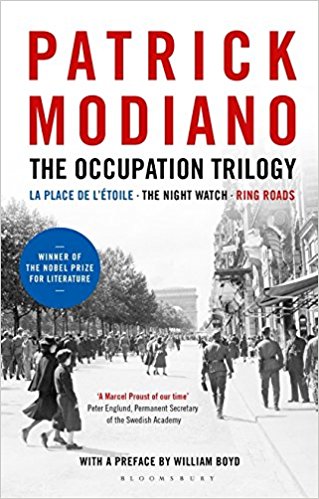

The three novels of the Occupation Trilogy, La Place de L’Etoile (1968), The Night Watch (1969), and Ring Roads (1972) are Patrick Modiano’s first three novels, published when he was twenty-two, twenty-three, and twenty-six years old, and they made the literary world wake up and pay attention – not only because they were so finely written (and were winners of three major literary prizes) but because of their youthful energy and the fact that Modiano illustrated and addressed directly the issue of French collaboration with the Germans during the Occupation from 1940 – 1944. Though more than twenty-five years had passed since the Occupation, this was an issue which had been avoided in French literature for almost all of the years which Modiano himself (1945 – present) was alive. Instead, postwar writers in France specialized in experimental new styles – the theatre of the absurd, surrealism, and existentialism, for example – as these more abstract styles evolved from the postwar horrors and saved them from having to address collaboration directly. Modiano had special reasons for wanting to know more about the Occupation. His father, a blackmarketeer during the war who was reputedly part of the Rue Lauriston Gang, had essentially abandoned him to the care of circus acrobats for his early childhood (until the acrobats were arrested for illegal activities), and he sees the war and its aftermath as major factors in his father’s later continuing absence from his life. Growing up without a mother (an actress who traveled the world) or a father, he transmits his feelings directly in these narratives in which several speakers tells stories of real life, which parallel his own feelings and, sometimes, circumstances from his own life.

The three novels of the Occupation Trilogy, La Place de L’Etoile (1968), The Night Watch (1969), and Ring Roads (1972) are Patrick Modiano’s first three novels, published when he was twenty-two, twenty-three, and twenty-six years old, and they made the literary world wake up and pay attention – not only because they were so finely written (and were winners of three major literary prizes) but because of their youthful energy and the fact that Modiano illustrated and addressed directly the issue of French collaboration with the Germans during the Occupation from 1940 – 1944. Though more than twenty-five years had passed since the Occupation, this was an issue which had been avoided in French literature for almost all of the years which Modiano himself (1945 – present) was alive. Instead, postwar writers in France specialized in experimental new styles – the theatre of the absurd, surrealism, and existentialism, for example – as these more abstract styles evolved from the postwar horrors and saved them from having to address collaboration directly. Modiano had special reasons for wanting to know more about the Occupation. His father, a blackmarketeer during the war who was reputedly part of the Rue Lauriston Gang, had essentially abandoned him to the care of circus acrobats for his early childhood (until the acrobats were arrested for illegal activities), and he sees the war and its aftermath as major factors in his father’s later continuing absence from his life. Growing up without a mother (an actress who traveled the world) or a father, he transmits his feelings directly in these narratives in which several speakers tells stories of real life, which parallel his own feelings and, sometimes, circumstances from his own life.

La Place d’Etoile (1968), Modiano’s debut novel at age twenty-two, explodes with the pent-up creative energy of an immature but sensitive young man, highly educated in literary traditions but perhaps naive about the implications of some of the philosophies he has espoused. Within a maelstrom of wild activity, Modiano creates a narrator, Raphael Schlemilovich, a young Jew turned Nazi sympathizer, who quickly reveals himself as unreliable as he advocates his ideas, lives or imagines a life for himself, explores literary movements, travels, and draws conclusions based on his (very) limited personal experience. All these ideas and many of the (real) people Schlemilovich mentions here existed in the waning days of World War II in which much of France was cooperating with the Gestapo and punishing their own citizens for believing in freedom. Though Modiano himself was born after this period, he sees it as part of his own life, believing that his father’s disinterest in him originated somehow during the war years, and that his father’s illegal activities have continued for years after the war was over.

Filled with the kind of imagination which young writers delight in exploring, Modiano here “lets things fly,” creating one of the wildest debut novels I have ever read as he obviously imagines himself in the role of Schlemilovich, committing every crime, betraying anyone who crosses him, and acting on every resentment that a talented, but personally neglected, twenty-two-year-old author might harbor against the rest of the world. Modiano does, however, reveal much from his own life through the voice of his narrator – his love of writing and fine literature, his difficulties with an absent father and equally absent actress mother, his enduring sense of irony and, remarkably, his humor. It is through these qualities that a sense of reality does intrude within the obvious fantasy of this picaresque and out-of-this-world novel. A full review of La Place de L’Etoile, with photos, may be found at this link.

Filled with the kind of imagination which young writers delight in exploring, Modiano here “lets things fly,” creating one of the wildest debut novels I have ever read as he obviously imagines himself in the role of Schlemilovich, committing every crime, betraying anyone who crosses him, and acting on every resentment that a talented, but personally neglected, twenty-two-year-old author might harbor against the rest of the world. Modiano does, however, reveal much from his own life through the voice of his narrator – his love of writing and fine literature, his difficulties with an absent father and equally absent actress mother, his enduring sense of irony and, remarkably, his humor. It is through these qualities that a sense of reality does intrude within the obvious fantasy of this picaresque and out-of-this-world novel. A full review of La Place de L’Etoile, with photos, may be found at this link.

The Night Watch (1969), set during that fraught period between the German occupation of France during World War II and the liberation which came four years later, is Patrick Modiano’s second novel, written when he was just twenty-three years old. This novel incorporates as his main character a young man, much like himself, who is at a total loss about what to do with his life. Describing the character as someone who “started out a pure and innocent soul,” he admits that his “innocence got lost along the way.” The people who are in contact with him now are criminals and former policemen, including an official now known as the Khedive, who operate a “detective agency” from which they are collecting protection money. The Khedive, who still has important contacts throughout the police department, has high hopes himself of eventually becoming “Monsieur le Prefet de Police.” The young main character, known only as “Swing Troubadour,” does dirty work for this group, sometimes referred to as “The Night Watch,” while earning a huge salary for his work. Possessing a warrant card and a gun license, the young man is ordered to infiltrate a “ring” of enemies and destroy it.

Though Modiano’s style here is more controlled, much less frantic, than it was in La Place de L’Etoile, written just the previous year, his use of a real plot in The Night Watch is still subject to quick changes of focus, time, and place. Living in an elegant house which he and the Khedive’s group have appropriated from a wealthy man who has escaped from France, Swing Troubadour, has helped sell off artwork, engaged in theft, committed beatings, and even participated in murder for “The Night Watch.” The conclusion, when it finally arrives, is suggested, rather than described in full, leaving the reader with mixed feelings. The rapid-fire narrative and its attendant flashes back and forth come to an end, not through any specific action, but because the author has decided that the highly flawed Swing Troubadour, who has touched the lives of his readers in some ways, now needs to travel the rest of the narrative on his own. A full review of The Night Watch, with photos, may be found by clicking this link.

Though Modiano’s style here is more controlled, much less frantic, than it was in La Place de L’Etoile, written just the previous year, his use of a real plot in The Night Watch is still subject to quick changes of focus, time, and place. Living in an elegant house which he and the Khedive’s group have appropriated from a wealthy man who has escaped from France, Swing Troubadour, has helped sell off artwork, engaged in theft, committed beatings, and even participated in murder for “The Night Watch.” The conclusion, when it finally arrives, is suggested, rather than described in full, leaving the reader with mixed feelings. The rapid-fire narrative and its attendant flashes back and forth come to an end, not through any specific action, but because the author has decided that the highly flawed Swing Troubadour, who has touched the lives of his readers in some ways, now needs to travel the rest of the narrative on his own. A full review of The Night Watch, with photos, may be found by clicking this link.

The third book in the trilogy, Ring Roads (1972) switches between two time periods, ten years apart, in an attempt to reconcile aspects of what Modiano has learned about his father, and, perhaps, himself. The novel opens with a speaker observing a photograph of three men at a bar, one of whom is his father, Chalva Deyckecaire, sometimes referred to as “Baron.” As he studies the three men, their posture, clothing, and jewelry, he imagines their positions real life relative to each other, concluding that his father is less important than the others. They are all living in a pretty village near the Forest of Fontainebleu, apparently in houses abandoned temporarily by their owners who have left to escape the war – large and elaborate houses filled with objets d’art, paintings, and antiques of all types. “There’s something suspicious about the whole thing,” the speaker remarks. “Who are these people? Where have they sprung from?” Within this milieu, the speaker becomes more familiar with his father and engages in suspicious activities with him. At one point, Chalva, the father, is selling counterfeit stamps, as his son, narrator Serge Alexandre, is having great success inscribing dedications from one famous author to another in the frontispieces of rare books which he sells at enormous prices. A dramatic event involving the speaker and his father at a Metro station dramatically ends their relationship.

The third book in the trilogy, Ring Roads (1972) switches between two time periods, ten years apart, in an attempt to reconcile aspects of what Modiano has learned about his father, and, perhaps, himself. The novel opens with a speaker observing a photograph of three men at a bar, one of whom is his father, Chalva Deyckecaire, sometimes referred to as “Baron.” As he studies the three men, their posture, clothing, and jewelry, he imagines their positions real life relative to each other, concluding that his father is less important than the others. They are all living in a pretty village near the Forest of Fontainebleu, apparently in houses abandoned temporarily by their owners who have left to escape the war – large and elaborate houses filled with objets d’art, paintings, and antiques of all types. “There’s something suspicious about the whole thing,” the speaker remarks. “Who are these people? Where have they sprung from?” Within this milieu, the speaker becomes more familiar with his father and engages in suspicious activities with him. At one point, Chalva, the father, is selling counterfeit stamps, as his son, narrator Serge Alexandre, is having great success inscribing dedications from one famous author to another in the frontispieces of rare books which he sells at enormous prices. A dramatic event involving the speaker and his father at a Metro station dramatically ends their relationship.

Without warning, time and reality shift, this time to ten years into the future, as the speaker has decided to look for his father once again, reconnecting with the criminal group and learning that his father acts as the front man for the trio. The speaker now realizes that any attempt to save his father is futile, and as he asserts himself, he, too, comes under the influence of the time and place in which this gang operates. He quickly learns that double-crosses are in process and that even human life is not sacred. Much of Modiano’s work incorporates parallels between the lives of his narrators, the actions of his protagonists, and the information Modiano himself has learned about his own family, but considering the literary milieu in which Modiano is living and writing, one in which the expressionists, the surrealists, and the existentialists are all experimenting with time, the missing connections in the conclusion here seem a small price to pay in this prizewinning novel by a twenty-six-year-old in search of himself. A full review of Ring Roads, with photos, may be found here

Note: Readers unfamiliar with Modiano may find that the best place to start reading this addictive author is with SUSPENDED SENTENCES, which gives much information about Modiano’s life as a young child. The Yale University Press edition of the book also includes two other novellas which show the author as a teen and as a college student – a easy introduction to the author for readers new to Modiano here at this link.

Note: Readers unfamiliar with Modiano may find that the best place to start reading this addictive author is with SUSPENDED SENTENCES, which gives much information about Modiano’s life as a young child. The Yale University Press edition of the book also includes two other novellas which show the author as a teen and as a college student – a easy introduction to the author for readers new to Modiano here at this link.

ALSO reviewed here: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, FAMILY RECORD, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (with Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay, LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), PARIS NOCTURNE, PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SLEEP OF MEMORY, SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Photos. The book covers are all from Amazon.com.

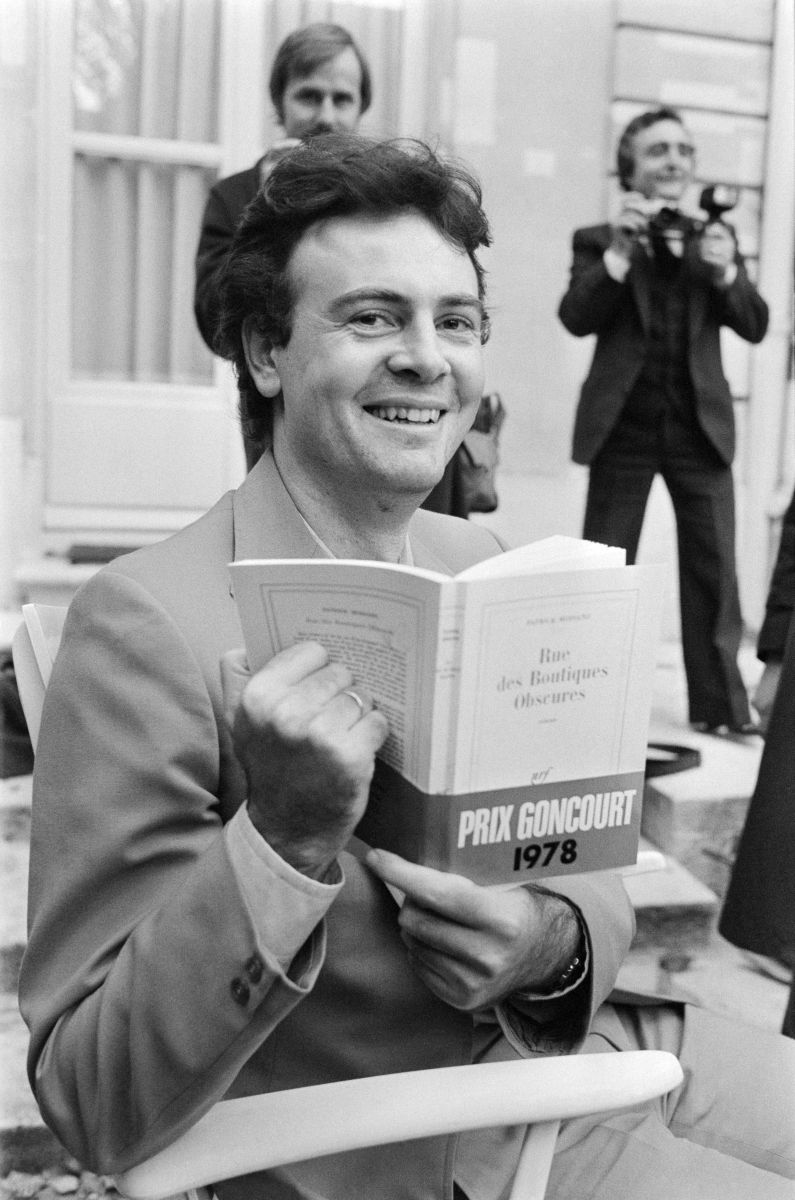

The first photo of a very young Patrick Modiano comes from https://www.newstatesman.com/

The second photo of the young Patrick is from https://www.goodreads.com

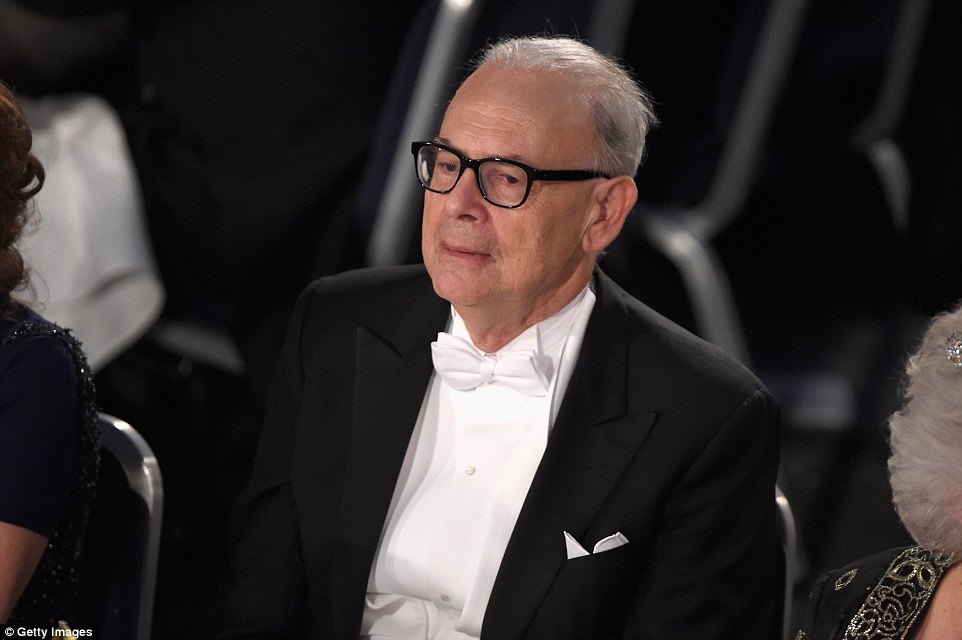

Patrick Modiano at his Nobel Prize ceremony appears on https://www.nytimes.com/