“[Seven-thirty p.m.] was the most dangerous time at Flodberga Prison. [That] was when the daily freight train thundered past; the walls shook and keys rattled and the place smelled of sweat and perfume. All the worst abuses took place then, masked by the racket from the railway…just before the cell doors were shut. Salander always let her gaze wander back and forth….Someone was slapping Faria Kazi…The abuse had been going on for a long time and had broken her will to resist.”

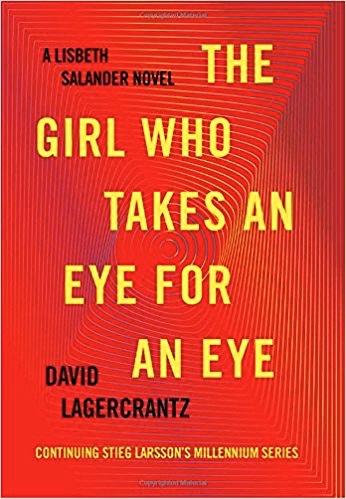

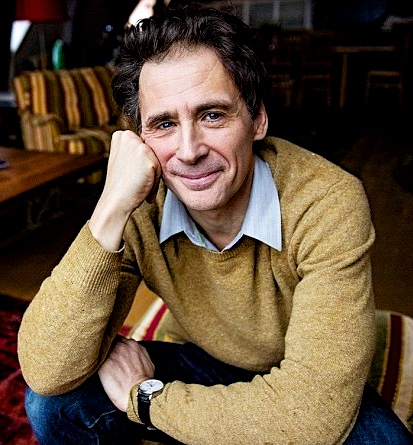

Lisbeth Salander is back in this continuation of the Millenium series started by Swedish author Steig Larsson and continued, following Larsson’s death in 2004, by David Lagercrantz. The raw energy and the violence of the three Larsson thrillers are more muted in the work of Lagercrantz, who was hired by Larsson’s heirs to continue the series, writing The Girl in the Spider’s Web and now The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye. Lagercrantz’s reliance on Salander, a damaged and reclusive computer hacker, and Mikael Blomquvist, a famed investigator and the founder of Millenium Magazine, to control the action is less obvious here than in Larsson’s novels, and he carefully includes identifying information for many of the earlier characters who repeat within this series, even including a helpful character list at the beginning. The complexity of the plot of this novel is clear early on if one looks at the character groupings within that character list: Lisbeth Salander and Mikael Blomqvist, listed separately, are followed by those in Lisbeth’s violent and sadistic family; those who have had an effect on Lisbeth’s adult life, for better or, more often, for worse; the organizations with which Lisbeth sometimes has contact – a thuggish motorcycle gang, an elite group of hackers, and a secret police faction with its own agenda; and the legitimate police who have investigated her. In the course of this novel, over two dozen new characters also make their appearances, as Lisbeth and Blomqvist, while still involved in the plot, take more limited roles and share the action with many others.

Lisbeth Salander is back in this continuation of the Millenium series started by Swedish author Steig Larsson and continued, following Larsson’s death in 2004, by David Lagercrantz. The raw energy and the violence of the three Larsson thrillers are more muted in the work of Lagercrantz, who was hired by Larsson’s heirs to continue the series, writing The Girl in the Spider’s Web and now The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye. Lagercrantz’s reliance on Salander, a damaged and reclusive computer hacker, and Mikael Blomquvist, a famed investigator and the founder of Millenium Magazine, to control the action is less obvious here than in Larsson’s novels, and he carefully includes identifying information for many of the earlier characters who repeat within this series, even including a helpful character list at the beginning. The complexity of the plot of this novel is clear early on if one looks at the character groupings within that character list: Lisbeth Salander and Mikael Blomqvist, listed separately, are followed by those in Lisbeth’s violent and sadistic family; those who have had an effect on Lisbeth’s adult life, for better or, more often, for worse; the organizations with which Lisbeth sometimes has contact – a thuggish motorcycle gang, an elite group of hackers, and a secret police faction with its own agenda; and the legitimate police who have investigated her. In the course of this novel, over two dozen new characters also make their appearances, as Lisbeth and Blomqvist, while still involved in the plot, take more limited roles and share the action with many others.

As the novel begins, Lisbeth is in Flodberga Prison, serving two months for violent actions she committed in the previous novel when she rescued a severely autistic child and hid him for his own safety. Though Blomqvist and his sister Annika Giannini, Lisbeth’s lawyer, were frustrated by Lizbeth’s failure to defend herself in court, she did not care. Prison, she thought, would offer her more time to be on her own, working without interference or threats from the outside world. Within twenty-five pages, however, Lisbeth is involved in trying to right new injustices within the prison. A young woman, Faria Kazi, from Bangladesh, someone so emotionally frail that Lizbeth regards her as a “human wreck,” is being abused by a female gang leader, “Benito” Andersson. The power mad “Benito” rules the unit, despite the presence of guards and the awareness of the prison warden and prison governor. Using her own skills, both physical and intuitive, Lisbeth manages to defuse some of these issues while also ensuring her own privilege of using a prison computer for an extended period of time one evening. She has been investigating some files from the past which she believes may explain aspects of her own early life and background.

Another plot line involves Blomqvist, who visits the imprisoned Lisbeth regularly each week. He has been investigating a hacker attack on financial markets in Brussels, especially as they impact a particular investment company, Alfred Ogren Securities. Blomqvist has noticed something strange on a recent video, involving an Alfred Ogren officer whose own life soon comes under scrutiny. Lisbeth’s former guardian and great friend, Holger Palmgren, also appears here. Palmgren has some issues regarding Lisbeth’s past, and though he is dying and in great pain, he has managed to visit her once. He has more papers related to her past – papers that she is desperate to study. At this point, the many coincidences and accompanying flashbacks begin, each flashback going back to eighteen months earlier than the current action. The flashbacks add information to what the author has already presented through the action, prolonging the suspense and sometimes connecting the various subplots.

Another plot line involves Blomqvist, who visits the imprisoned Lisbeth regularly each week. He has been investigating a hacker attack on financial markets in Brussels, especially as they impact a particular investment company, Alfred Ogren Securities. Blomqvist has noticed something strange on a recent video, involving an Alfred Ogren officer whose own life soon comes under scrutiny. Lisbeth’s former guardian and great friend, Holger Palmgren, also appears here. Palmgren has some issues regarding Lisbeth’s past, and though he is dying and in great pain, he has managed to visit her once. He has more papers related to her past – papers that she is desperate to study. At this point, the many coincidences and accompanying flashbacks begin, each flashback going back to eighteen months earlier than the current action. The flashbacks add information to what the author has already presented through the action, prolonging the suspense and sometimes connecting the various subplots.

Blomqvist plans to hear a talk at the Fotografiska Museet by someone he suspects of being an innocent participant in the Genetic Study conducted 25 years ago.

Eventually, the files from the “Registry for the Study of Genetics and Social Environment,” being perused separately by Lisbeth and Blomqvist, introduce new characters whose connections to existing characters come as little surprise, while their danger to the “scientists” involved in secret genetic studies becomes obvious. By this point, over twenty-five years have passed since research began on a select group of children, and all that remains is to keep track of the test subjects, several of whom, including Lisbeth, are involved in the action and flashbacks here. The implications of this study could bring down high officials in business and in government. Lisbeth, “the girl who takes an eye for an eye,” is particularly vengeful. The conclusion, which has plenty of action, also involves some violence, though it is less grotesque, less “juicy,” than what appears in the Larsson novels. Some parts of the conclusion even suggest that there are alternatives to the “eye for an eye” mentality which permeates the series.

Click to enlarge. St. George and the Dragon by Sten Sture in 1489 is something that especially impresses Lisbeth, even inspiring her to think in new directions. Note the woman in the bottom left. Photo by Nairon.

Dedicated readers of the series to date may find that this novel feels a bit “old.” Lisbeth is a difficult character to like, though it is easy to feel sorry for her, and her need for real emotional help is obvious. Whether Lagercrantz has future plans to help her remains to be seen. In the meantime, much credit is due to him for keeping the large cast of characters, many from previous novels, on track in this one. I was disappointed, however, in the amount of coincidence used here to make convenient connections among the subplots. The flashbacks, the first of which begins one-third of the way through the book, become increasingly prevalent – and annoying – with nine or ten of them in the last half of the book alone. While these artificial devices can be used to prolong suspense and add bits of information slowly, they also prevent the kind of identification a reader usually gains from “sharing” the characters’ lives as they actually happen. In one powerful and memorable incident, however, Lisbeth shares her feelings for the first time ever, commenting on Sten Sture’s sculpture of St. George and the Dragon, which includes a female observing the killing of a fire-breathing dragon. “I had never seen [this statue] as a monument to a heroic deed,” Lisbeth says, “but rather as a representation of a terrible assault….[But] the same fire that can turn us into ashes and waste…can become something totally different; a force which allows us to fight back,” she believes, a new idea for Lisbeth and perhaps the future.

The af Chapman Youth Hostel, located in an old sailing ship, is where a character stayed when he returned to Sweden from overseas. It still operates as a hostel. Photo by Brorsson

ALSO by Steig Larsson: THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO, THE GIRL WHO PLAYED WITH FIRE, THE GIRL WHO KICKED THE HORNET’S NEST.

By David Lagercrantz: THE GIRL IN THE SPIDER’S WEB, THE GIRL WHO LIVED TWICE

Photos: The author’s photo is from http://www.dailymail.co.uk

The photo of the woman in jail appears on https://www.hrw.org/

The Fotografika Museet, where Blomqvist planned to hear a character speak, is here: https://www.pinterest.com

Sten Shure’s 1489 statue of St. George and the Dragon made an enormous impressing on Lisbeth Salander when she noticed the woman in the bottom left. Click to enlarge. https://en.wikipedia.org/

The af Chapman Youth Hostel, where one character stays upon his return to Sweden after a trip overseas, is located on a retired sailing ship and is still being used. https://en.wikipedia.org/

Set in the aftermath of World War II in the southwestern countryside outside of Oslo, Gaute Heivoll’s emotionally engrossing novel involves big themes, a sense of involvement by the reader, and some lingering questions at the end. The novel draws its action from life in an extended family, where both the mother and father, parents of the unnamed young narrator, had worked as nurses and caregivers at a psychiatric hospital in Dikemark for eleven years. Devoutly religious, they cared for their patients with a “Christlike spirit of love.” When the father’s old family home in the country burned to the ground during their time in Dikemark, just before the war, the parents looked on the bright side and decided they would rebuild on the site, creating “their own little asylum in the midst of the parish where Papa was born and grew up, a place Mama had not yet seen.” Carefully designing their new home so that they could care for the “mentally disabled,” they eventually created an upstairs floor which had a large kitchen, spacious and light-filled rooms, special staircases with lower steps, and doors with large handles which could be locked only from the outside – a place where people in need of special care could feel safe, “their own little Dikemark.”

Set in the aftermath of World War II in the southwestern countryside outside of Oslo, Gaute Heivoll’s emotionally engrossing novel involves big themes, a sense of involvement by the reader, and some lingering questions at the end. The novel draws its action from life in an extended family, where both the mother and father, parents of the unnamed young narrator, had worked as nurses and caregivers at a psychiatric hospital in Dikemark for eleven years. Devoutly religious, they cared for their patients with a “Christlike spirit of love.” When the father’s old family home in the country burned to the ground during their time in Dikemark, just before the war, the parents looked on the bright side and decided they would rebuild on the site, creating “their own little asylum in the midst of the parish where Papa was born and grew up, a place Mama had not yet seen.” Carefully designing their new home so that they could care for the “mentally disabled,” they eventually created an upstairs floor which had a large kitchen, spacious and light-filled rooms, special staircases with lower steps, and doors with large handles which could be locked only from the outside – a place where people in need of special care could feel safe, “their own little Dikemark.”

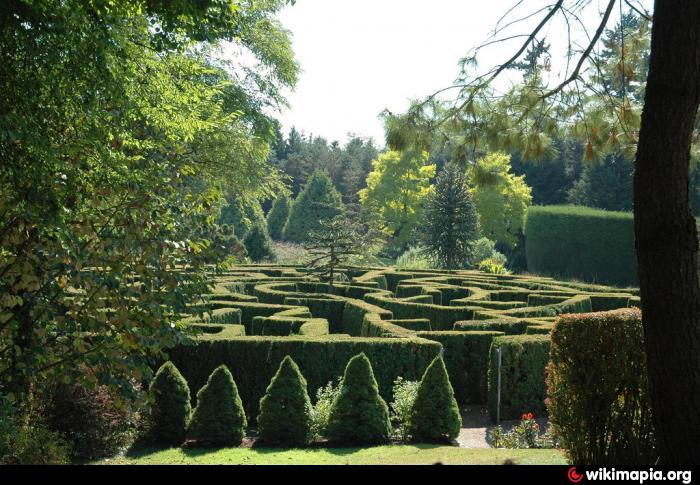

The image of Valvert, described above, sets the tone and establishes many of the themes for this often dream-like collection of interconnected stories, filled with mysteries and riddles. Valvert, the former owner of the property on which the Valvert School was later built, accompanied the Comte D’Artois when he abandoned France during the French Revolution, and later fought his former countrymen in France as part of a Russian regiment. At the Battle of Austerlitz, described as “the greatest victory ever achieved by Napoleon,” in 1805, he lost his life fighting for a foreign army. Clearly, revolutionary democracy was not a goal or even a consideration for Valvert. An elite friend of French royalty, he lived an elegant and privileged life, fleeing France when his life was in danger and he could no longer live there in the style he enjoyed. The building which became the school on Valvert’s property, built by a later owner at the end of the nineteenth century, was, ironically, a copy of Malmaison, the castle where Napoleon and Josephine lived during Napoleon’s war with the rest of Europe and Britain. With a history like this, it is no surprise that the Valvert School, with its Castle and its past history might appeal to parents interested in preserving the appearance, atmosphere, and values of the elite.

The image of Valvert, described above, sets the tone and establishes many of the themes for this often dream-like collection of interconnected stories, filled with mysteries and riddles. Valvert, the former owner of the property on which the Valvert School was later built, accompanied the Comte D’Artois when he abandoned France during the French Revolution, and later fought his former countrymen in France as part of a Russian regiment. At the Battle of Austerlitz, described as “the greatest victory ever achieved by Napoleon,” in 1805, he lost his life fighting for a foreign army. Clearly, revolutionary democracy was not a goal or even a consideration for Valvert. An elite friend of French royalty, he lived an elegant and privileged life, fleeing France when his life was in danger and he could no longer live there in the style he enjoyed. The building which became the school on Valvert’s property, built by a later owner at the end of the nineteenth century, was, ironically, a copy of Malmaison, the castle where Napoleon and Josephine lived during Napoleon’s war with the rest of Europe and Britain. With a history like this, it is no surprise that the Valvert School, with its Castle and its past history might appeal to parents interested in preserving the appearance, atmosphere, and values of the elite.

During his Fulbright Program in Egypt, beginning in 2009, debut novelist Ian Basingthwaighte had personal, daily contact with the horrors of displaced families – not just Egyptians but throughout the Middle East – as they flooded Cairo seeking help from the legal aid organization in which he worked helping refugees. Each day, he saw their scars and heard their stories as they left their homes, and often their families, to flee for their lives and the lives of their children. Unfortunately, getting to Cairo, often by foot, the goal of most of these refugees, does not guarantee the solutions they seek, no matter how much they are willing to give up. As the Liaison for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees points out in the opening quotation of this review, the size of the crisis is just too great. Setting his book in 2011, just after the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and the student revolt in Tahrir Square, which students hoped would change the nature of Egyptian government, Basingthwaighte creates a moving and absorbing novel of the human costs borne by innocent victims of the religious and political strife throughout the Middle East.

During his Fulbright Program in Egypt, beginning in 2009, debut novelist Ian Basingthwaighte had personal, daily contact with the horrors of displaced families – not just Egyptians but throughout the Middle East – as they flooded Cairo seeking help from the legal aid organization in which he worked helping refugees. Each day, he saw their scars and heard their stories as they left their homes, and often their families, to flee for their lives and the lives of their children. Unfortunately, getting to Cairo, often by foot, the goal of most of these refugees, does not guarantee the solutions they seek, no matter how much they are willing to give up. As the Liaison for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees points out in the opening quotation of this review, the size of the crisis is just too great. Setting his book in 2011, just after the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and the student revolt in Tahrir Square, which students hoped would change the nature of Egyptian government, Basingthwaighte creates a moving and absorbing novel of the human costs borne by innocent victims of the religious and political strife throughout the Middle East.