Last year when I looked at the ten most-read reviews on this website, I was struck by how many of these most-read reviews were for classics, instead of more recent books. This year I’ve been struck by how many of these books are recent, displacing most of the classics from last year.

Seven of the ten most-read books on this list are new to the list this year. Only three from last year survived the cut. Those are marked with an asterisk. Most on the list are relatively new books, a couple of them very new! The countries represented by these books are given in parentheses at the end of each listing.

- *THE REDEEMER by Jo Nesbo is a perennial favorite (for reasons I still do not understand). It’s not one of Nesbo’s most popular novels, and it’s not my favorite Nesbo book, yet it’s been #1 on the list for the past three years. For those interested, THE REDBREAST is my favorite Nesbo novel, though his new MIDNIGHT SUN and BLOOD ON SNOW, signal a whole new, more literary, style for Nesbo, a style I like much better than the blood-and-gore of the past. (Norway)

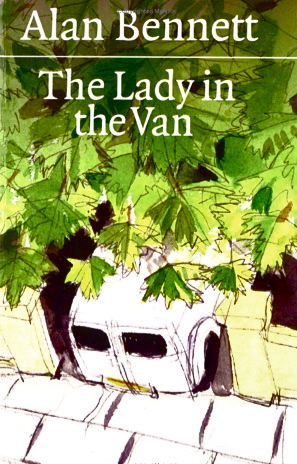

- THE LADY IN THE VAN by Alan Bennett. This real-life story of Bennett’s kindness to an elderly eccentric who parks her van in his driveway and lives in it for sixteen years, combined with his hilarious accounts of her behavior, on occasion, make this one a true classic. (England). The trailer from the UK film of the same title (with Maggie Smith) is included at the bottom of the review.

- *ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE by Anthony Doerr, a new classic of World War II and the people who suffered and triumphed. (France, Germany, World War II).

- THE PROSPECTOR by J. M. G. LeClezio. Not widely known in the U. S. when he won the Nobel Prize in 2008, LeClezio has seen his works translated into English since then. This review is one of the earliest reviews posted for one of his works. (Mauritius)

- RU by Kim Thuy. Winner of the Governor General’s Award in Canada in 2010, this is a story about a family of “boat people” who settled in Canada as they create new lives while remembering their pasts. (Vietnam, Canada)

- *THE HARE WITH AMBER EYES by Edmund de Waal. Another new classic, and one of my favorite books. It is the story of several generations of the author’s family, now living in England, and a fabulous art collection (lost during World War II in Austria and France) from which only a collection of Japanese netsuke (including the “hare with amber eyes”) remains. The author, an artist, tells the story of this collection, which becomes a microcosm for the war. (France, Austria, Japan)

- THE TSAR OF LOVE AND TECHNO by Anthony Marra. A huge surprise to me, since this book is a short story collection which has been out for only eight months! Ambitious and energetic, it focuses on Russia, Chechnya, Siberia, St. Petersburg, and the old Soviet Union.

- MIDNIGHT SUN by Jo Nesbo. This novel is the second of a new, more literary, style for Nesbo. Significantly less violence, more attention to genuine feelings and sensibilities. I was hugely surprised, and extremely pleased by this new style, and this novel, just released in February, 2016, must be “getting legs” since it’s in the top ten of all these reviews after just five months! (Norway)

- THE DOOR by Magda Szabo, one of Hungary’s most celebrated authors. Rich and incredibly powerful novel of the relationship of a writer and her uncompromising housekeeper who is stronger than she is for much of the novel. This was Szabo’s last novel (written in 2005), republished by NYRB in Jan. 2015. On my favorites list for this year, and unforgettable.

- MY BRILLIANT FRIEND by Elena Ferrante. The first of the novels in the Neapolitan Quartet by Ferrante, a determinedly private author, this begins the story of the relationship between two women from Naples – one whose academic pursuits become paramount, and one who remains working in a store in her Neapolitan neighborhood. Over about forty years, four volumes, and almost 1700 pages in the quartet, Ferrante reconstructs their loves and lives. (Reviews of the second and third novels are also on the site.)

Books from the 2015 list which have fallen from the top ten are:

WAITING FOR AN ANGEL by Helon Habila (Nigeria)

THE LOST BOOKS OF THE ODYSSEY by Zachary Mason (Greece)

THE HERO OF CURRIE ROAD by Alan Paton (South Africa)

KARTOGRAPHY by Kamila Shamsie (Pakistan)

PIAF: A PASSIONATE LIFE by David Bret (France)

THE ART OF HEARING HEARTBEATS by Jan-Phiipp Sendker (Burma/Myanmar)

PARADISE by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Kenya, Tanzania)

In this quotation of just eighty words from the first page of Hell’s Gate, author Richard Crompton establishes the Kenyan prison setting, its sights, sounds and smells, its fraught atmosphere, the state of mind of the prisoner, his cultural background, the antagonistic attitude of the guard, and the guard’s triumphant, even delighted, threatening of his prisoner. It is not because the prisoner is a Maasai that he is likely to be tormented, however. In this case, the prisoner is also known as Detective Mollel of the Nairobi police. Mollel had been a Maasai moran twenty years ago until he left his roots in “Maasai-land” in southern Kenya to begin work as a policeman in Nairobi, hoping to bring justice to Kenya’s hard-working poor within an atmosphere in which corruption is a way of life. For even the most dedicated police officers, creating a sense of peace is often more important than bringing pure justice, and Mollel has been a constant trial to many of his superiors and to the judicial system. Constantly challenging and questioning them, he is also cursed with a hair-trigger temper and willingness to do violence to bring about “justice.” This has resulted in his being moved around among police departments throughout the country. Now he is imprisoned for an unspecified crime, and he must somehow survive among a number of former policemen he helped send to jail.

In this quotation of just eighty words from the first page of Hell’s Gate, author Richard Crompton establishes the Kenyan prison setting, its sights, sounds and smells, its fraught atmosphere, the state of mind of the prisoner, his cultural background, the antagonistic attitude of the guard, and the guard’s triumphant, even delighted, threatening of his prisoner. It is not because the prisoner is a Maasai that he is likely to be tormented, however. In this case, the prisoner is also known as Detective Mollel of the Nairobi police. Mollel had been a Maasai moran twenty years ago until he left his roots in “Maasai-land” in southern Kenya to begin work as a policeman in Nairobi, hoping to bring justice to Kenya’s hard-working poor within an atmosphere in which corruption is a way of life. For even the most dedicated police officers, creating a sense of peace is often more important than bringing pure justice, and Mollel has been a constant trial to many of his superiors and to the judicial system. Constantly challenging and questioning them, he is also cursed with a hair-trigger temper and willingness to do violence to bring about “justice.” This has resulted in his being moved around among police departments throughout the country. Now he is imprisoned for an unspecified crime, and he must somehow survive among a number of former policemen he helped send to jail.

For long-time readers of this website, it will be no secret that I regard James Sallis as far more than the “noir mystery writer” that he is often labeled. A specialist in spare, minimalist writing that is compressed, incisive, and often metaphorical, he is a writer who takes literary chances and whose recent work has been as experimental as it has been insightful. One of the best literary writers in the United States, in my opinion, Sallis has always been concerned with questions of innocence and guilt, strength and weakness, and the past and its effects on the present and future. He creates often sad, damaged characters doing the best they can in a noir atmosphere in which they must fight their own demons in order to have any chance of success. His earliest novels, a series of mysteries set in the southern United States, are dark and gothic without the sentimentality so common to that genre, and his later books, set in the west, are more psychological, stories of people living on the edge whose lives could go in any direction depending on chance and circumstance. His main characters make mistakes, sometimes big ones, but at heart they have an intrinsic sense of honor despite their closeness to violence.

For long-time readers of this website, it will be no secret that I regard James Sallis as far more than the “noir mystery writer” that he is often labeled. A specialist in spare, minimalist writing that is compressed, incisive, and often metaphorical, he is a writer who takes literary chances and whose recent work has been as experimental as it has been insightful. One of the best literary writers in the United States, in my opinion, Sallis has always been concerned with questions of innocence and guilt, strength and weakness, and the past and its effects on the present and future. He creates often sad, damaged characters doing the best they can in a noir atmosphere in which they must fight their own demons in order to have any chance of success. His earliest novels, a series of mysteries set in the southern United States, are dark and gothic without the sentimentality so common to that genre, and his later books, set in the west, are more psychological, stories of people living on the edge whose lives could go in any direction depending on chance and circumstance. His main characters make mistakes, sometimes big ones, but at heart they have an intrinsic sense of honor despite their closeness to violence.

In an electrifying novel that uses simple images and straightforward, often abbreviated thoughts to create deep emotions and subtle themes, debut novelist Max Porter revitalizes the whole concept of the novel, creating a work that includes elements of many different literary styles which offer constant surprises as the novel shifts and turns in its focus. Despite these constantly changing structural elements, the voices of Dad and his Boys remain direct, unpretentious, and realistic as they tell of their reactions to the sudden death of their wife and mother from an accident which has left them overwhelmed by events and not sure how to react or acknowledge what they feel. In a consummate irony, Dad, an academic writer, has been working on a book, overdue at the publisher, called Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis, which examines the poems of Ted Hughes following the death of his wife, Sylvia Plath.

In an electrifying novel that uses simple images and straightforward, often abbreviated thoughts to create deep emotions and subtle themes, debut novelist Max Porter revitalizes the whole concept of the novel, creating a work that includes elements of many different literary styles which offer constant surprises as the novel shifts and turns in its focus. Despite these constantly changing structural elements, the voices of Dad and his Boys remain direct, unpretentious, and realistic as they tell of their reactions to the sudden death of their wife and mother from an accident which has left them overwhelmed by events and not sure how to react or acknowledge what they feel. In a consummate irony, Dad, an academic writer, has been working on a book, overdue at the publisher, called Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis, which examines the poems of Ted Hughes following the death of his wife, Sylvia Plath.

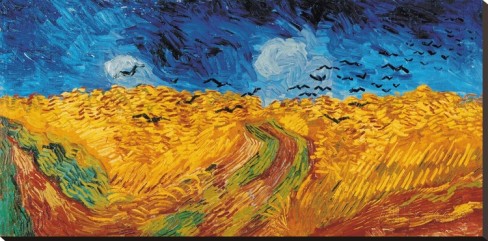

Artist Vincent Van Gogh’s earnest attempts to live a productive life while also burdened by crushing sadness and isolation come to life through author Nellie Hermann’s insightful depiction of his life as a missionary in a coal mining village. Depicting Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) before he became an artist, she focuses on the period of 1879 – 1880, when Van Gogh was living in the remote Borinage mining area of southwest Belgium, near the French border. The young son of a Dutch Reformed preacher, the twenty-seven-year-old Van Gogh had worked for several years in the Goupil & Cie gallery and its showrooms in the Hague, London, and Paris, before studying theology to become a minister and missionary, like his father. His long, descriptive letters to his younger brother Theo, used as resources by the author, provide intimate glimpses of his life in the Borinage, including the misery he shared with the miners and their families, which his own depression may have exacerbated. Though he loved art, he did not exhibit the kind of talent in his own work which would have made him successful, at that time, and he had failed both his theology exam and his course at a Protestant missionary school before heading to the Borinage on his own religious mission. His father, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, considered him an “idler.”

Artist Vincent Van Gogh’s earnest attempts to live a productive life while also burdened by crushing sadness and isolation come to life through author Nellie Hermann’s insightful depiction of his life as a missionary in a coal mining village. Depicting Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) before he became an artist, she focuses on the period of 1879 – 1880, when Van Gogh was living in the remote Borinage mining area of southwest Belgium, near the French border. The young son of a Dutch Reformed preacher, the twenty-seven-year-old Van Gogh had worked for several years in the Goupil & Cie gallery and its showrooms in the Hague, London, and Paris, before studying theology to become a minister and missionary, like his father. His long, descriptive letters to his younger brother Theo, used as resources by the author, provide intimate glimpses of his life in the Borinage, including the misery he shared with the miners and their families, which his own depression may have exacerbated. Though he loved art, he did not exhibit the kind of talent in his own work which would have made him successful, at that time, and he had failed both his theology exam and his course at a Protestant missionary school before heading to the Borinage on his own religious mission. His father, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, considered him an “idler.”