“It was the commissario’s theory that behind every murder were either hunger or love, the two eternal forces that ensured the survival of the human race. And so, each time he was confronted with a case, he did his best to figure out which of the two was directly responsible for the crime he was investigating. He’d never been wrong yet: one of these two faces of passion had always been at the root of the motive.”

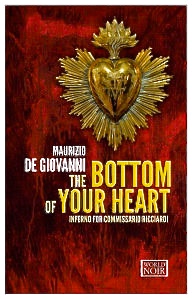

Maurizio de Giovanni just keeps getting better and better. With this seventh novel in his series featuring Baron Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi di Malomonte, Commissario of Public Safety at the Royal Police Headquarters in Naples, he creates a new mystery which takes place during the reign of Benito Mussolini in the early 1930s. At the same time, de Giovanni also continues to develop the stories of the many repeating characters throughout the series to date. It is the new developments in the personal, very human stories of these characters – who represent all aspects of Neapolitan society, from the saintly to the criminal – which make the series so much fun to read. De Giovanni is less interested in the blood and gore aspects of mystery writing than he is in conveying a time and place and the effects of crimes on the ordinary people who live in the neighborhoods of Naples, and many fans of the series will want to read this latest installment especially for updates on the lives of the repeating characters they have come to know and love.

Maurizio de Giovanni just keeps getting better and better. With this seventh novel in his series featuring Baron Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi di Malomonte, Commissario of Public Safety at the Royal Police Headquarters in Naples, he creates a new mystery which takes place during the reign of Benito Mussolini in the early 1930s. At the same time, de Giovanni also continues to develop the stories of the many repeating characters throughout the series to date. It is the new developments in the personal, very human stories of these characters – who represent all aspects of Neapolitan society, from the saintly to the criminal – which make the series so much fun to read. De Giovanni is less interested in the blood and gore aspects of mystery writing than he is in conveying a time and place and the effects of crimes on the ordinary people who live in the neighborhoods of Naples, and many fans of the series will want to read this latest installment especially for updates on the lives of the repeating characters they have come to know and love.

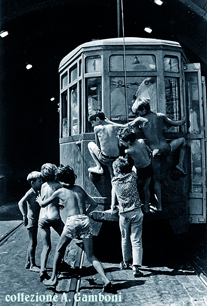

De Giovanni, unlike most other mystery writers, also enhances his plots with episodes of humor, not just bleak, dark humor and irony, but sometimes the kind of humor one most associates with slapstick or burlesque episodes, and he succeeds in doing this without weakening the effects of the tragedies which have suddenly struck the families of his victims. The Bottom of Your Heart takes place in July during the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel at the Basilica del Carmine Maggiore, during the most brutal heat of summer. Here, De Giovanni, who well knows Neapolitan summers, provides a full chapter of vivid description, from the images of the little, near-naked scugnizzi orphans hitching rides on the trams to cool off, to the welcome appearance of the ice man, the strolling vendors, and the almost motionless people at the beaches – “it’s too hot to move much in a sea that doesn’t even cool you off for long.”

De Giovanni, unlike most other mystery writers, also enhances his plots with episodes of humor, not just bleak, dark humor and irony, but sometimes the kind of humor one most associates with slapstick or burlesque episodes, and he succeeds in doing this without weakening the effects of the tragedies which have suddenly struck the families of his victims. The Bottom of Your Heart takes place in July during the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel at the Basilica del Carmine Maggiore, during the most brutal heat of summer. Here, De Giovanni, who well knows Neapolitan summers, provides a full chapter of vivid description, from the images of the little, near-naked scugnizzi orphans hitching rides on the trams to cool off, to the welcome appearance of the ice man, the strolling vendors, and the almost motionless people at the beaches – “it’s too hot to move much in a sea that doesn’t even cool you off for long.”

During these few days of especially intense heat, “the atmosphere changes,” as the heat arrives “straight from hell.” This “Inferno for Inspector Ricciardi” (the subtitle of this novel) features a gruesome murder which draws Brigadier Maione, Ricciardi’s closest friend, and Dr. Modo, the crotchety medical examiner, into the investigation. The victim, Tullio Iovine del Castello, the director of gynecology at the general hospital of the royal university of Naples, had plenty of enemies, and Commissario Ricciardi goes to the site immediately in response. Ricciardi has a talent (and a curse) which he has inherited from his mother: If he goes to the scene of a violent death and listens carefully, he can hear the final thoughts of the victim. This time, the victim’s thoughts do not give him any clues about the murder.

The Immacolatella Palace on the Naples waterfront is where an anonymous young boy and young girl meet frequently to talk about their distant futures. Note the passenger ship lurking in the background.

Because the victim was thrown from a window in his fifth floor office, Ricciardi and his team know from the outset that the murderer is very large, very strong. Several people involved with the professor fit that description – Francesco Ruspo di Roccasole, who lost the chance to become the eventual successor to Iovine; Guido Ruspo, the enormous son of Ruspo, whom Iovine flunked three times during medical studies; and Peppino the Wolf, the gangster husband of a former patient who died during an agonizing labor because Iovine could not be reached for hours. A mysterious couple, who have loved each other since they were children, but who had to separate “temporarily” in their late teens, also adds complications to the murder as the male character, who remains anonymous, tells the reader that, years later, he is still waiting for the woman to whom he pledged his heart forever. His connection, if any, to Iovine remains a mystery as he pours out his heart in first-person reminiscences.

The Caffe Gambrinus , a fixture in this series, is a place for meetings and for relaxing quietly alone. Enrica’s father goes there to read privately. Photo by Armando Mancini.

In addition to the story of the murder, the continuing characters who have appeared throughout the whole series continue their lives where they left off in Viper, de Giovanni’s previous novel. Ricciardi, in his early thirties, is still single, living with his tata, who has brought him up, but he is worried about her health as she is now in her seventies, and he welcomes the arrival of her niece, Nelide, to help her out. Ricciardi’s assistant, Brigadier Maione, begins to feel that his marriage to his beloved Lucia is in trouble, and he becomes petulant and mean-spirited, dramatically different from his normal demeanor. Livia, the widow of the world’s greatest tenor, now in Naples from Rome, is still flirting with Ricciardi, and Enrica, the girl across the alley who has loved Ricciardi from afar for years, now works as a busy school teacher.

Bambinella, the transvestite who has often provided Maione with information, shares with him one of the novel’s funniest scenes, late in the story, and Garzo, the deputy police chief, reappears demanding entrée to a high society party to which he has not been invited. A new character, Coviello, a goldsmith, inspires a motif regarding the creation of “ex voto” images to be donated to the Basilica del Carmine Maggiore in memory of a special event or person.

As always here, the Caffe Gambrinus is the characters’ “go to” place for get-togethers and chats, or simply as a place to spend some quiet time.

The “burning” of the bell tower at the Basillica, one of the highlights of the festival of the Madonna Bruno.

DeGiovanni’s ability to describe Naples fully, from the brutally hot weather to the preparations for its festivals and the religious traditions behind them, brings Naples and its people to life. The “burning” of the bell tower to honor La Madonna Bruna at the Basilica del Carmine Maggiore, is one of the summer’s most anticipated events, and Maione’s six children can hardly wait for it. Numerous other scenes of the community’s activity bring readers closer to understanding the pure delight which daily life in Naples sometimes offers to its residents. Mussolini has almost no influence on the action here, and, except for a murder or two, life feels comfortable and emotionally satisfying throughout. The most highly developed and complex novel of the series to date, The Bottom of My Heart is also one of the liveliest and most satisfying, though de Giovanni does save a number of questions to be answered in the future.

ALSO by de Giovanni. Insp. Ricciardi series: I WILL HAVE VENGEANCE (#1), BLOOD CURSE (#2), EVERYONE IN THEIR PLACE (#3), THE DAY OF THE DEAD (#4), BY MY HAND (#5), VIPER (#6), THE BOTTOM OF YOUR HEART (#7), GLASS SOULS: MOTHS FOR COMMISSARIO RICCIARDI (#8), NAMELESS SERENADE (#9),

Lojacono series: THE CROCODILE (#1), THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#2), DARKNESS FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#3), COLD FOR THE BASTARDS OF PIZZOFALCONE (#4), PUPPIES (#5)

Photo, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.lacooltura.com

The scugnizzi on the trolley are from http://www.clamfer.it/

The Immacolatella Palace in the Naples harbor, is where the anonymous young girl and young boy dream of the future and where the adult boy/man remembers their commitment. https://en.wikipedia.org/

The Caffe Gambrinus, featured throughout this series, is where characters meet to talk and where single people meet to escape the normal pressures of life. Photo by Armando Mancini on https://en.wikipedia.org/

The photo of the ex votos is by Fiore S. Barbato on https://www.flickr.com/

The “burning” of the bell tower at the Basilica Santuario del Carmine Maggiore is a high point of the festival of the Madonna Bruno.

ARC: Europa Editions

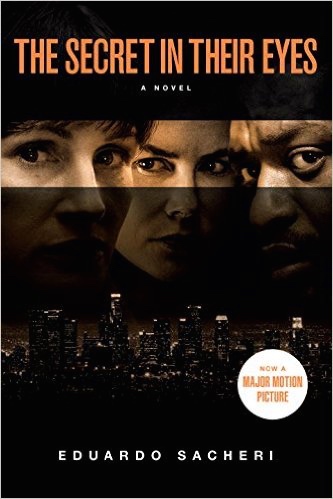

Five years ago, the Spanish language film of this novel from Argentina won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film of 2010, and the subtitled version went on to become as big a success with film aficionados in the US as it had been with the Academy and Spanish-speaking audiences. Now a new film, in English, starring Julia Roberts and Nicole Kidman, is being released this month, and Other Press, which published the earlier novel on which the film is based, is reissuing it this month. Here, novelist Eduardo Sacheri’s extremely colloquial Spanish has been translated into equally colloquial English by John Cullen, and he has made his main characters so life-like that all differences in culture, background, and time frame disappear during the thirty-year time frame of the novel.

Five years ago, the Spanish language film of this novel from Argentina won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film of 2010, and the subtitled version went on to become as big a success with film aficionados in the US as it had been with the Academy and Spanish-speaking audiences. Now a new film, in English, starring Julia Roberts and Nicole Kidman, is being released this month, and Other Press, which published the earlier novel on which the film is based, is reissuing it this month. Here, novelist Eduardo Sacheri’s extremely colloquial Spanish has been translated into equally colloquial English by John Cullen, and he has made his main characters so life-like that all differences in culture, background, and time frame disappear during the thirty-year time frame of the novel.

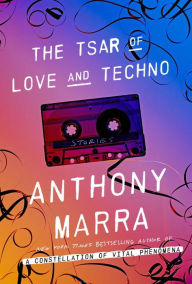

itious and energetic books of the year, Anthony Marra defies the limitations of genre by creating a book of epic status which hovers, structurally, between the novel and a collection of interrelated short stories, incorporating the best aspects of both genres. Setting the book in Siberia, Chechnya, and Leningrad/St. Petersburg between 1937 and 2013, he creates characters and their families who appear and reappear throughout the book. Often introduced in their own long stories, they and their heirs move back and forth across time slipping into the stories of other characters from the same location and adding complexity as the reader sees new aspects of their lives. A number of symbols also unite the time periods and characters – a pastoral painting by 19th century artist Pyotr Zakharov-Chechenetz, a family photograph from 1906, a print of a leopard by Henri Rousseau, a mix-tape – all of which, being portable, can move among the different settings. Specific locations within these various settings, such as Kresty Prison in St. Petersburg, the White Forest in Kirovsk, the Grozny Museum of Art, reappear as new episodes from different time periods take place, providing unity and connection over the seventy-five year expanse of Russian history.

itious and energetic books of the year, Anthony Marra defies the limitations of genre by creating a book of epic status which hovers, structurally, between the novel and a collection of interrelated short stories, incorporating the best aspects of both genres. Setting the book in Siberia, Chechnya, and Leningrad/St. Petersburg between 1937 and 2013, he creates characters and their families who appear and reappear throughout the book. Often introduced in their own long stories, they and their heirs move back and forth across time slipping into the stories of other characters from the same location and adding complexity as the reader sees new aspects of their lives. A number of symbols also unite the time periods and characters – a pastoral painting by 19th century artist Pyotr Zakharov-Chechenetz, a family photograph from 1906, a print of a leopard by Henri Rousseau, a mix-tape – all of which, being portable, can move among the different settings. Specific locations within these various settings, such as Kresty Prison in St. Petersburg, the White Forest in Kirovsk, the Grozny Museum of Art, reappear as new episodes from different time periods take place, providing unity and connection over the seventy-five year expanse of Russian history.

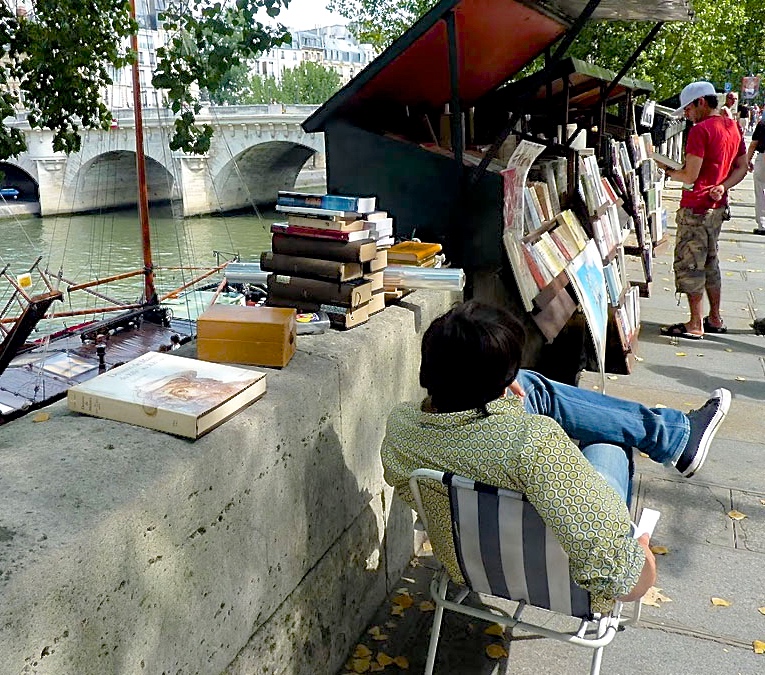

Remembering and forgetting underlie many of French author Patrick Modiano’s stories as he creates almost dreamlike images and sequences which fade in and out as the time frame changes, often unexpectedly. New images and memories seem to force themselves into his consciousness, only to vanish back into the netherworld from which they have come. Almost as famous for the bizarre and often cruel life he experienced as a child as he is for his Nobel Prize for Literature, Modiano, through his novels, mines his own past for clues as to who he was and who and what he has become. Repeating images and events include references to his absent parents and the circus people with whom he once stayed, some of whom engaged in unlawful activities, reinforcing the idea that the only love and care Modiano knew as a child came from strangers. His parents had no real interest in him after his birth in 1945, his mother traveling the world as a second-rate actress and his father continuing the black marketeering in which he engaged during World War II. His father’s world travels to obtain black market goods kept him out of the country for long periods of time in the postwar era and left Patrick and his younger brother Rudy unattended except for hired caretakers like the circus employees whom his father paid to look after them for several years.

Remembering and forgetting underlie many of French author Patrick Modiano’s stories as he creates almost dreamlike images and sequences which fade in and out as the time frame changes, often unexpectedly. New images and memories seem to force themselves into his consciousness, only to vanish back into the netherworld from which they have come. Almost as famous for the bizarre and often cruel life he experienced as a child as he is for his Nobel Prize for Literature, Modiano, through his novels, mines his own past for clues as to who he was and who and what he has become. Repeating images and events include references to his absent parents and the circus people with whom he once stayed, some of whom engaged in unlawful activities, reinforcing the idea that the only love and care Modiano knew as a child came from strangers. His parents had no real interest in him after his birth in 1945, his mother traveling the world as a second-rate actress and his father continuing the black marketeering in which he engaged during World War II. His father’s world travels to obtain black market goods kept him out of the country for long periods of time in the postwar era and left Patrick and his younger brother Rudy unattended except for hired caretakers like the circus employees whom his father paid to look after them for several years.

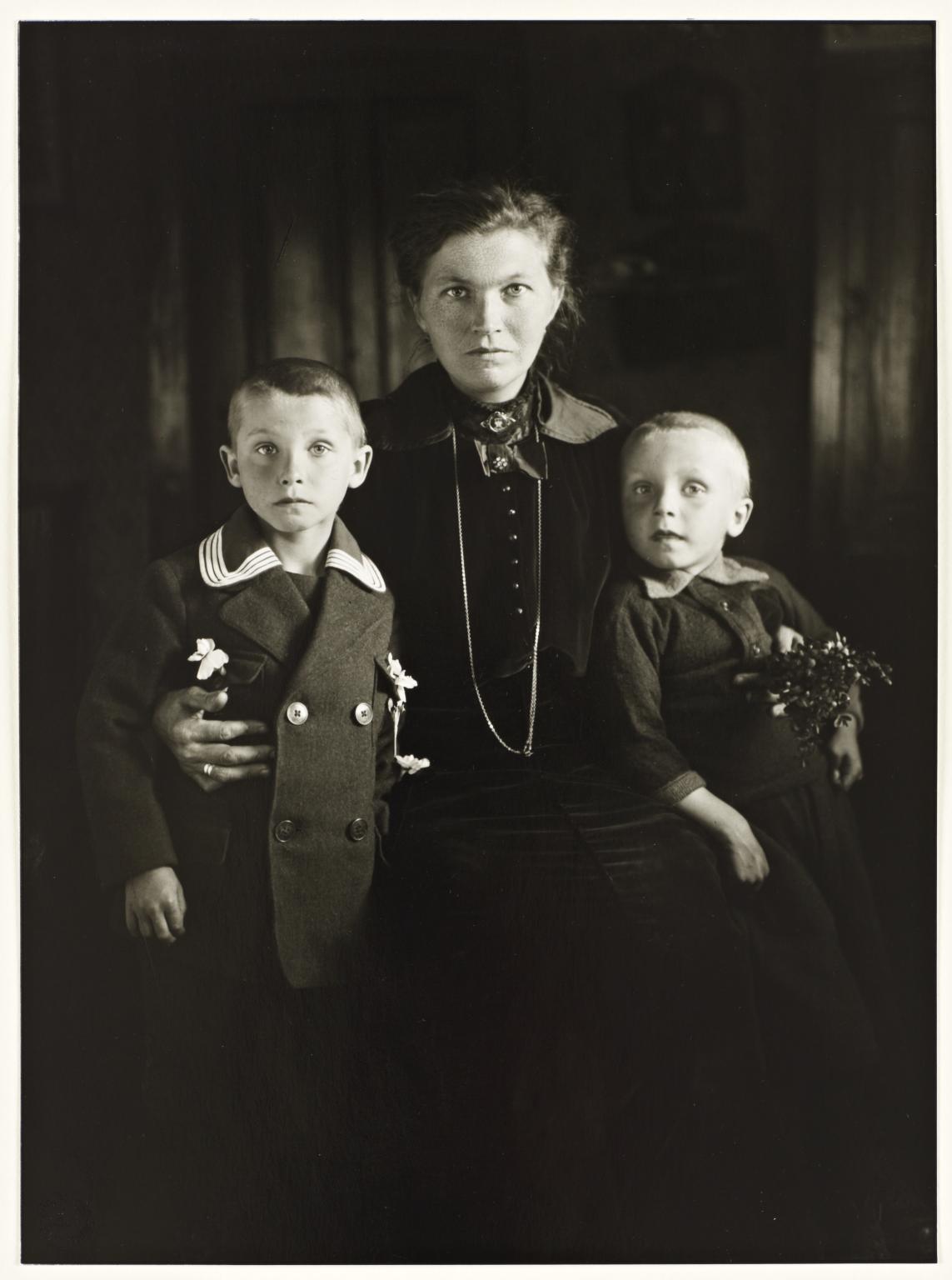

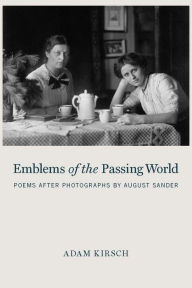

The same question may be asked of all forty-five other photographic portraits by Sander, a world-renowned photographic artist (1876 – 1964). Upon contemplating Sander’s portraits from 1910 through the 1940s, poet Adam Kirsch has invented lives for the real people behind these portraits, none of whom are named, and all of whom are identified in Sander’s work by only a few words regarding their places in society. In Part I, they are all working class people identified by their jobs; in Part II, they are people of the middle and professional classes, educated and often talented; in Part III, they are wives and working women; and in Part IV, they are people who represent the future and its terrible uncertainties. The cover photo here, identified as “Small-Town Women,” imagines two women thinking about “Business and law the church and government,/Making a living, having a career–/Things that their brothers and their husbands spent /Their lives on seem unnecessary here,/ In this small parlor where the window’s shut/Airtight, and only beams of light convey/News of the world beyond the haven that/They are condemned to occupy all day.”

The same question may be asked of all forty-five other photographic portraits by Sander, a world-renowned photographic artist (1876 – 1964). Upon contemplating Sander’s portraits from 1910 through the 1940s, poet Adam Kirsch has invented lives for the real people behind these portraits, none of whom are named, and all of whom are identified in Sander’s work by only a few words regarding their places in society. In Part I, they are all working class people identified by their jobs; in Part II, they are people of the middle and professional classes, educated and often talented; in Part III, they are wives and working women; and in Part IV, they are people who represent the future and its terrible uncertainties. The cover photo here, identified as “Small-Town Women,” imagines two women thinking about “Business and law the church and government,/Making a living, having a career–/Things that their brothers and their husbands spent /Their lives on seem unnecessary here,/ In this small parlor where the window’s shut/Airtight, and only beams of light convey/News of the world beyond the haven that/They are condemned to occupy all day.”