“I’m trying to impose some order on my memories. Every one of them is a piece of the puzzle, but many are missing, and most of them remain isolated. Sometimes I manage to connect three or four, but no more than that. So I jot down bits and pieces that come back to me in no particular order, lists of names or brief phrases. I hope that these names, like magnets, will draw others to the surface, and that those bits of sentences might end up forming paragraphs and chapters that link together.” – Patrick Modiano

I have made no secret of the fact that I am addicted to the work of French author Patrick Modiano, having read, at this point, well over a dozen of his novels and novellas. I was hooked from the day I read Suspended Sentences, a novella about his early childhood, in which his black-marketeer father and his absent actress mother abandoned him and his younger brother Rudy to the care of a group of circus acrobats who lived near an abandoned chateau. These acrobats were arrested several months later for criminal activities, leading to a new chapter in Patrick Modiano’s life. Since reading that account, I have also become familiar with Modiano’s later life in a boarding school, in some summer activities when he was of college age, and in his early years as a writer, times which are a focus of additional Modiano works. The one period which Modiano has not described in detail until now includes the five years from the time he was seventeen until he was twenty-two, a time which every parent knows can often be crisis-filled and laden with events which may affect the maturing teen for life. For Modiano, who had virtually no family life and was forced to make most of his decisions without the aid of supportive adults, this was a fraught time about which he still has questions, described in this review’s opening quotation.

I have made no secret of the fact that I am addicted to the work of French author Patrick Modiano, having read, at this point, well over a dozen of his novels and novellas. I was hooked from the day I read Suspended Sentences, a novella about his early childhood, in which his black-marketeer father and his absent actress mother abandoned him and his younger brother Rudy to the care of a group of circus acrobats who lived near an abandoned chateau. These acrobats were arrested several months later for criminal activities, leading to a new chapter in Patrick Modiano’s life. Since reading that account, I have also become familiar with Modiano’s later life in a boarding school, in some summer activities when he was of college age, and in his early years as a writer, times which are a focus of additional Modiano works. The one period which Modiano has not described in detail until now includes the five years from the time he was seventeen until he was twenty-two, a time which every parent knows can often be crisis-filled and laden with events which may affect the maturing teen for life. For Modiano, who had virtually no family life and was forced to make most of his decisions without the aid of supportive adults, this was a fraught time about which he still has questions, described in this review’s opening quotation.

Sleep of Memory, Modiano’s first published work since he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014, draws together many of his early memories of these late teens and early twenties, often in fragments, which have haunted him from the mid-1960s. It is by far the most intimate picture he has given of his life, which feels so real here that it is hard to imagine that it is “fictionalized.” He recalls these years as “a time of encounters, in a long-distant past,” admitting that he “was prone back then to a fear of emptiness, like a kind of vertigo.” Many of his memories from this period, not surprisingly, are connected with girls and women. The first “memory” here is of “Stioppa’s daughter,” when he is fifteen. He thinks she might have been the daughter of one of his father’s Russian connections in the French black-market, and he hopes that she will “help [him] understand [his] father, a stranger…” but though he telephones her often, she never calls him back.

Sleep of Memory, Modiano’s first published work since he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2014, draws together many of his early memories of these late teens and early twenties, often in fragments, which have haunted him from the mid-1960s. It is by far the most intimate picture he has given of his life, which feels so real here that it is hard to imagine that it is “fictionalized.” He recalls these years as “a time of encounters, in a long-distant past,” admitting that he “was prone back then to a fear of emptiness, like a kind of vertigo.” Many of his memories from this period, not surprisingly, are connected with girls and women. The first “memory” here is of “Stioppa’s daughter,” when he is fifteen. He thinks she might have been the daughter of one of his father’s Russian connections in the French black-market, and he hopes that she will “help [him] understand [his] father, a stranger…” but though he telephones her often, she never calls him back.

Modiano describes Genevieve and her role in his life in 1964, and then again in 1970, when he meets her at the botanical gardens and zoo to get caught up on her life.

By seventeen, Modiano’s relationships with women have become more realistic and much more complex. On one occasion he leaves the Haute-Savoie, where he is in boarding school, and heads to Paris, where he appears at his mother’s apartment, only to discover that his mother has moved out. He spends two weeks living with the woman who has moved in, going to a cabaret at night and accompanying her and an actor friend who might have been part of the parapolice group involved in the Algerian War. By age nineteen he is living in Paris, where he becomes friends with Genevieve Dalame, a woman he has met at an occult bookstore. Through Genevieve, he also meets Madeleine Peraud, who lives in a elegant apartment where she, Genevieve, and a secret society practice “magic” with a group, which may or may not be a cult connected with George Ivanovich Girdjieff, “a spiritual teacher.” Mysteries surround all these people, their lives, and their motives, and Genevieve Dalame’s eventual disappearance is a warning sign that things may not be as they appear. Other people enter, then leave Modiano’s life, and one person threatens him, forcing him to use violence to escape. Years later, he seeks out some of these people and places, often finding surprising connections among them.

One person, Madame Hubersen, is someone he wants to erase from his memory permanently, though he tells himself that his relationship with her in 1965, when he is twenty, “is all so far in the past that it’s covered by what the law calls amnesty.” Other references to “witnesses” and “the statute of limitations” confirm the suggestions that something terrible – and possibly illegal – happened with Madame Huberson, and that he is seriously involved. Living at the Hotel Alsina in Montmartre with her for the rest of the summer, he is not sure what his future holds, but he reads many books about the occult and about psychology in an effort to come to terms with what has happened and might yet happen to her and to him. Still subject to upsetting memories, he finds Hervey de Saint-Denys’s book Dreams and How to Direct Them to be particularly helpful in redirecting his daydreams, his fears, his occasional panic, and his obsessions.

Leon d’Hervey de Saint-Denys’s Dreams and How to Direct Them, a book that the speaker found very helpful during his fraught time in 1965.

As Modiano sorts through his memories and opens up more and more to the reader, he is coming to terms with his own needs and the decisions he has made in his life, even as early as age seventeen. Though he is on his own during those years, he is, however, intelligent, sensitive, and, most importantly, literate and talented in writing, which eventually sees him through some of the most difficult situations a young adult could ever face alone. He is quick to tell us that a turning point occurred about five years after the events with Madame Hubersen: “I was living in Montmartre…with the woman I loved. The neighborhood was not the same. Neither was I….The Montmartre of summer 1965, as I thought I envisioned it in memory, suddenly seemed to me an imaginary Montmartre. And I no longer had anything to fear.” Thirty years ago, he says, he blended some of the details of that terrifying summer into a novel so that “no one would know whether they belonged to reality or the realm of dreams,” and though one could also say that we do not know how much of what Modiano says here about the episode with Mme Hubersen is real and how much is fiction, it feels absolutely real, as do the fear and the sense of guilt. This is Modiano’s most personal and revelatory book, one which his fans will appreciate, while they may also be left wondering….

ALSO by Modiano, reviewed here: AFTER THE CIRCUS, DORA BRUDER, FAMILY RECORD, HONEYMOON, IN THE CAFE OF LOST YOUTH, LA PLACE de L’ETOILE (Book 1 of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), (Patrick Modiano and Louis Malle–LACOMBE LUCIEN, a screenplay LITTLE JEWEL, THE NIGHT WATCH (Book II of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), THE OCCUPATION TRILOGY (LA PLACE DE L’ETOILE, THE NIGHT WATCH, AND RING ROADS), PARIS NOCTURNE , PEDIGREE: A Memoir, RING ROADS (Book III of the OCCUPATION TRILOGY), SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, SUCH FINE BOYS, SUNDAYS IN AUGUST, SUSPENDED SENTENCES, VILLA TRISTE, YOUNG ONCE

Post-Nobel Prize books: SLEEP OF MEMORY (2017), INVISIBLE INK (2019)

Photos. The photo of the author as a young man is from https://www.pinterest.com

The author as a mature man is from http://www.grreporter.info/en/

The Hotel Alcina in Montmartre, where the speaker and Mme. Hubersen lived for the summer may be found here: http://intentionalmama.com/

The sign from the botanical gardens and zoo, where the speaker met Genevieve Dalame six years after the events of his teen years appears on http://intentionalmama.com/

The panoramic photo of Montmartre is found here: https://propertylistings.ft.com

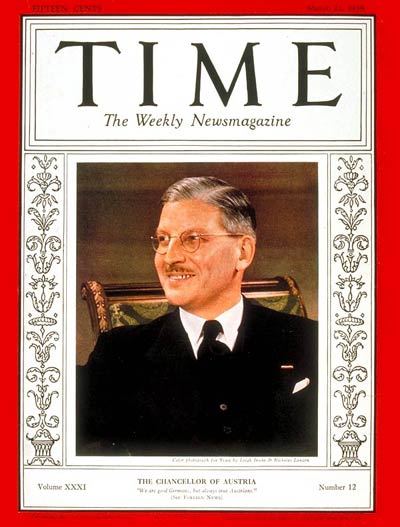

Eric Vuillard’s latest prizewinner opens with the secret arrival of twenty-four wealthy industrialists at the Berlin palace of the President of the Assembly in 1933.

Eric Vuillard’s latest prizewinner opens with the secret arrival of twenty-four wealthy industrialists at the Berlin palace of the President of the Assembly in 1933.

In the opening scene of Kate Atkinson’s new novel about the UK’s espionage during World War II, a sixty-year-old woman, “Miss Armstrong,” is lying in the street, badly injured after being hit by a car.

In the opening scene of Kate Atkinson’s new novel about the UK’s espionage during World War II, a sixty-year-old woman, “Miss Armstrong,” is lying in the street, badly injured after being hit by a car.

In The Only Story, British author Julian Barnes returns to examine, once again, some of his most encompassing themes. As in his Booker Prize-winning

In The Only Story, British author Julian Barnes returns to examine, once again, some of his most encompassing themes. As in his Booker Prize-winning