“[Marian’s] present life seemed episodic…She felt she was drifting through a neutral space, where there was neither love nor hate, neither danger nor safety, neither peace nor war; a place where crude, physical emotion—a raging heart, a sweating forehead, a rising panic—was triggered by simuli she couldn’t apprehend, while the feelings she ought to own, of contentment, of filial love, of sexual attraction even, were no more than vague memories.”

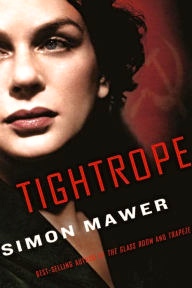

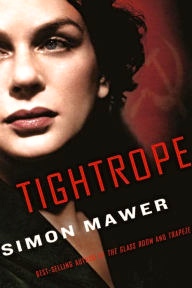

In his newest novel, Simon Mawer continues the story of Marian Sutro, whose wartime exploits he introduced in Trapeze (2012), and it is Marian’s difficulties dealing with the complex aftereffects of World War II which become the focus of this novel. In Trapeze, Marian was a composite character representing the women who served as members of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) between May, 1941, and September, 1944. After training in England, Marian, in 1943, was dropped by parachute into France to help liberate a former flame, Clement Pelletier, from his research lab in France and get him aboard a small plane to England. The emphasis here is on the action and bravery of Marian and her cohorts, with little real character development for the “composite character.”

In his newest novel, Simon Mawer continues the story of Marian Sutro, whose wartime exploits he introduced in Trapeze (2012), and it is Marian’s difficulties dealing with the complex aftereffects of World War II which become the focus of this novel. In Trapeze, Marian was a composite character representing the women who served as members of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) between May, 1941, and September, 1944. After training in England, Marian, in 1943, was dropped by parachute into France to help liberate a former flame, Clement Pelletier, from his research lab in France and get him aboard a small plane to England. The emphasis here is on the action and bravery of Marian and her cohorts, with little real character development for the “composite character.”

In Tightrope, by contrast, Mawer focuses especially on the development and detail of Marian Sutro’s character, and as he continues the story of Marian, he makes her come very much alive here as an individual recovering in England from traumas, both physical and psychological, rather than as a symbol of the larger group of SOE.

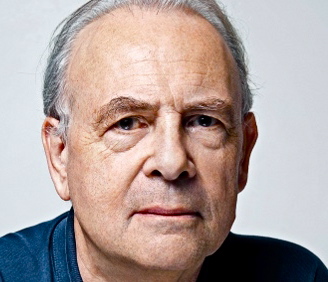

Author photo by Connie Bonello.

Tightrope opens in the present, when Marian is eighty. The speaker of the opening chapter is sixty-eight, a man who has obviously been involved in state security in England for his whole career and someone Marian has known since he was a child, though they have not seen each other in many years. For some reason, he has been drawn out of retirement to interview her about her war-time past during World War II and the Cold War which followed. Mawer creates suspense about Marian, someone who “had spent time in captivity in one of the concentration camps” and had survived, though she herself never talked about it. The speaker, whom we later learn is “Sam,” the son of a family friend, had once been told by his father that Marian was “dangerous,” and he himself “can fully attest to that.” He has now been sent to meet her, he says, because “they want to close the file. There’s no question of prosecution…They just want to tie up loose ends.” Marian is still interested, even now, however, in knowing if there was a mole at the top of the intelligence organization for which she had been working, and wants to know if Sam and those he works for will tell her if she was betrayed. His response, even at this late stage of history, is that everything is still “unofficial and therefore deniable.” Even Sam is not sure whether she is a heroine or a traitor.

Women like Marian imprisoned at Ravensbruck in Germany.

Marian’s story moves back and forth in time, opening in 1945, when she returns “home,” and it is here that the reader learns, with Marian, that of the forty women dispatched to France in 1943, only twenty-six have survived. Fourteen others were arrested or are missing, including many of Marian’s personal friends. She herself spent eighteen months in Ravensbruck, a German prison camp, tortured, beaten, and at war’s end, barely alive, and she knows that others from her group died there. When she becomes the first SOE member to return to England, intelligence interrogates her for information. As she recalls her friends and their fates, she cannot help wondering, yet again, if a high-level mole might have betrayed them. Further flashbacks show Marian making some dramatic decisions – in one case, a decision for which she will feel guilt for the rest of her life.

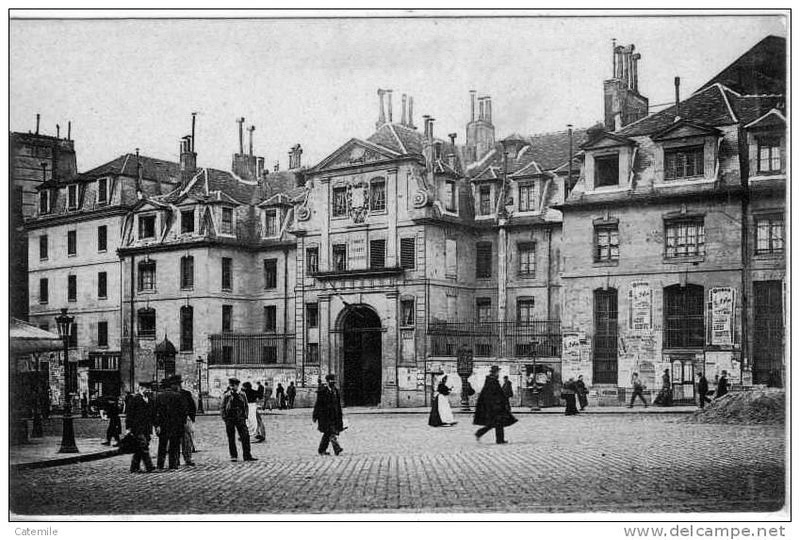

Piccadilly Square, August 11, 1945, as the country celebrates the end of the war.

The “business of war,” by intelligence professionals working for their country from behind desks, contrasts with the extraordinary sacrifices made by their recruits in the field, and Mawer brings these people and their sacrifices to life. Many intelligence workers lead double lives filled with compromises, with one person working in France for Major Fawley in British intelligence even acting as a pimp who tries to recruit Marian to “escort” German officers. Ultimately, after the injuries and deaths of thousands of soldiers and intelligence workers from other countries, including women from SOE, French General Charles De Gaulle, brands them all as “mercenaries” and expels them from France while he celebrates the French Resistance. When the war is over, the land-based intelligence service remains in business while their recruits return home, many of them traumatized. When Marian arrives at the family residence in Oxford, she must finally come to terms with the horrors of war-time: As she puts it, “it’s like suddenly finding yourself on the edge of a cliff, with nothing to stop you stepping over the edge…I was a good skier, I’ve parachuted, for God’s sake. And now…sometimes I find it hard to stand on the front doorstep.” Her psychological problems form the backbone of this part of the novel.

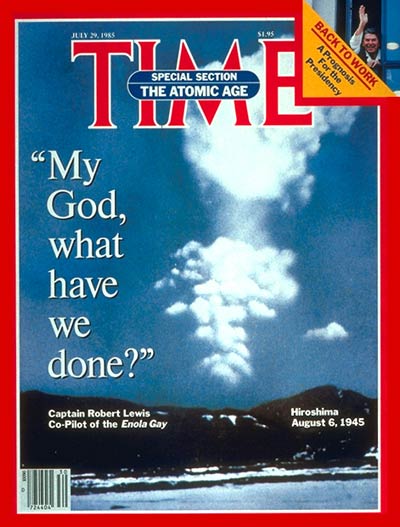

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. All that is left is the entrance to a temple and the remains of a cart.

In the last section of the book, the Americans’ use of the first two atomic weapons in history changes the dynamic of war, as Britain and France fear the spread of these weapons to other countries. The Soviet Union, which had been an ally during the war, now looks much more dangerous, and Marian becomes involved in doing Cold War spy work, leading to a whole new series of episodes in a newer time frame. Marian has often used sex as a way to deal with the uncertainties, even horrors, of her intelligence experience, and here she finds herself in love with a new man, though she is not averse to seducing others if it suits her purpose. A trip to the British Museum and a visit to see “Ginger,” the Gebelein Man from Egypt, over 5500 years ago, opens a whole new set of issues regarding violence and raises, once again, the question of betrayal by someone from their own side.

Marion unexpectedly met someone from her own past when she went to the British Museum to see the exhibit of “Ginger,” the Gebelein Man, from 3500 B.C. “Ginger” died a violent death, murdered when he had his back turned.

Filled with excitement and beautifully paced, the novel does suffer to some degree from its divisions into unnamed sections, which divide the reader’s focus during the novel – Marian’s background and early days in intelligence in France in the first section, her capture by the Germans, along with her psychological aftereffects in the next section, and finally her work with the Russians during the Cold War. The action is complex, filled with many characters (some of whom, including Marian, have multiple names), but the novel is intelligent and thought-provoking, filled with tension and beautifully drawn and well-developed settings, both physical and emotional. Marian becomes a real person here, however flawed she may be, showing the moral conundrums involved in intelligence work and what it requires. Ultimately, the reader must wonder how much leeway someone may allow himself in compromising situations without also betraying important values.

ALSO by Simon Mawer: TRAPEZE, THE GLASS ROOM, PRAGUE SPRING

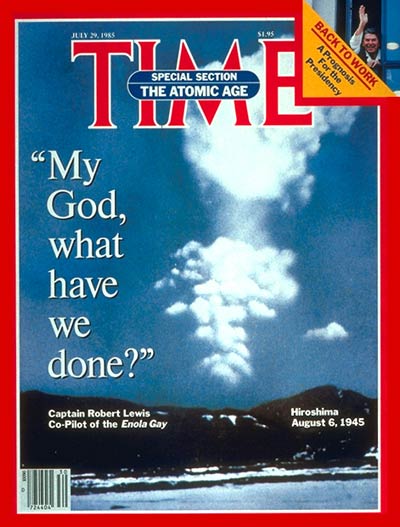

The 40th anniversary of the atomic bomb is acknowledged by Time Magazine on August 6, 1985.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Connie Bonello is from the New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com

The Ravensbruck prison camp in Germany is shown in http://www.jewishjournal.com

Piccadilly Square, August 11, 1945, erupted in celebration at the end of World War II, shown on http://www.telegraph.co.uk

The devastation of Hiroshima shows only the entrance to a temple and a ruined cart. http://www.ww2australia.gov.au/vevp/abomb.html

Ginger, the Gebelein Man, from Egypt, was murdered 5500 years ago. Photo by The British Museum. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

The Time Magazine cover is from http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19850729,00.html

ARC: Other Press.

TIGHTROPE

REVIEW. World War II, Cold War, England, France, Historical, Mystery, Thriller, Noir, Psychological study, Social and Political Issues

Written by: Simon Mawer

Published by: Other Press

Date Published: 11/03/2015

ISBN: 978-1590517239

1. Once again, with more than twice as many hits as any other review on the site: Norwegian author Jo Nesbo’s THE REDEEMER, always a surprise, is top of the list, though it is not my favorite Nesbo novel (THE REDBREAST is).

1. Once again, with more than twice as many hits as any other review on the site: Norwegian author Jo Nesbo’s THE REDEEMER, always a surprise, is top of the list, though it is not my favorite Nesbo novel (THE REDBREAST is).

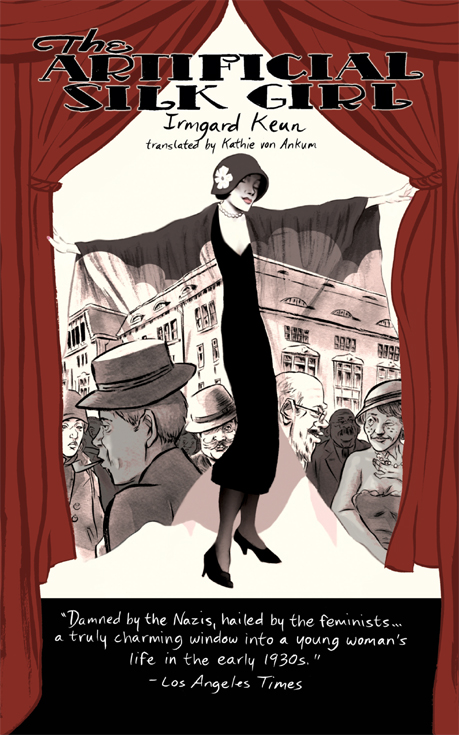

6. NEW— BIG SURPRISE: Banned by the Nazis in 1933 and rediscovered in the 1970s, this book has just this year been translated into English for the first time. Irmgard Keun’s THE ARTIFICIAL SILK GIRL, published in Germany in 1932, is said to be for pre-Nazi Germany what Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) is for Jazz Age America.

6. NEW— BIG SURPRISE: Banned by the Nazis in 1933 and rediscovered in the 1970s, this book has just this year been translated into English for the first time. Irmgard Keun’s THE ARTIFICIAL SILK GIRL, published in Germany in 1932, is said to be for pre-Nazi Germany what Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) is for Jazz Age America.

Hilary Mantel has never hesitated to say exactly what she means, and her descriptive abilities leave no room for doubt about exactly why she believes as she does. Though she is praised for her elegant turns of phrase when those are appropriate, she is equally skilled at stating, in no uncertain terms, her opinions about less elegant subjects. When Mantel’s recent short story collection, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher was first published in September, 2014, Mantel found herself on the front News page of the London Daily Mail, having done the unthinkable by imagining a story in which a man with Irish ties decides to assassinate the then-Prime Minister. Margaret Thatcher had died only a year before the story was published, and the public and many politicians were outraged by this story, with some calling for a police investigation of author Mantel while others bemoaned her “unquestionably bad taste.” Mantel held her ground, telling the Guardian in 2014 that she “feels boiling detestation” for Thatcher and considers her an “antifeminist psychological transvestite who did long-standing damage to the UK.”

Hilary Mantel has never hesitated to say exactly what she means, and her descriptive abilities leave no room for doubt about exactly why she believes as she does. Though she is praised for her elegant turns of phrase when those are appropriate, she is equally skilled at stating, in no uncertain terms, her opinions about less elegant subjects. When Mantel’s recent short story collection, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher was first published in September, 2014, Mantel found herself on the front News page of the London Daily Mail, having done the unthinkable by imagining a story in which a man with Irish ties decides to assassinate the then-Prime Minister. Margaret Thatcher had died only a year before the story was published, and the public and many politicians were outraged by this story, with some calling for a police investigation of author Mantel while others bemoaned her “unquestionably bad taste.” Mantel held her ground, telling the Guardian in 2014 that she “feels boiling detestation” for Thatcher and considers her an “antifeminist psychological transvestite who did long-standing damage to the UK.”

Through a young narrator, whose real name is unclear for most of this book, French author Patrick Modiano constantly muses about the past as it intrudes on the present, filled with imperfect and incomplete memories as they appear and reappear in the young man’s life throughout this novel. The narrator’s present has always been colored and perhaps distorted by the emotions of his past, and he worries that if he obsesses too much about the past and tries to rethink it too often, that he may lose whatever sense of confidence and reconciliation he feels about these events. In the vivid scene from which the introductory quotation, above, is taken, for example, the young man/narrator is nineteen years old, living at his estranged father’s apartment in Paris following his father’s sudden move to Switzerland to avoid criminal prosecution in France.

Through a young narrator, whose real name is unclear for most of this book, French author Patrick Modiano constantly muses about the past as it intrudes on the present, filled with imperfect and incomplete memories as they appear and reappear in the young man’s life throughout this novel. The narrator’s present has always been colored and perhaps distorted by the emotions of his past, and he worries that if he obsesses too much about the past and tries to rethink it too often, that he may lose whatever sense of confidence and reconciliation he feels about these events. In the vivid scene from which the introductory quotation, above, is taken, for example, the young man/narrator is nineteen years old, living at his estranged father’s apartment in Paris following his father’s sudden move to Switzerland to avoid criminal prosecution in France.

One out of Two, an early (1994) novel by award-winning Mexican author Daniel Sada, has just been published in English translation for the first time – a tragicomic classic by an author whom both Roberto Bolano and Carlos Fuentes have highly praised for his “contributions to literature in the Spanish language.” It joins

One out of Two, an early (1994) novel by award-winning Mexican author Daniel Sada, has just been published in English translation for the first time – a tragicomic classic by an author whom both Roberto Bolano and Carlos Fuentes have highly praised for his “contributions to literature in the Spanish language.” It joins

Though the novella is simple to understand, Sada has some remarkably subtle touches, making the reality of the sisters’ love for each other real in proportion to the jealousy of one and the triumph of the other. Their long interdependence has commanded their lives, and the fear of abandonment and hostility is real for both of them. As the action develops, the reader and the twins themselves soon conclude that the Gamals are neither the “saints” nor the “single pureness” which the narrator originally believed them to be. Their separate desires, dreams, and hopes for the future, forged as they are from their noticeably different personalities, surge forth under the stress of Oscar Segura’s courtship. The conclusion may surprise some, but I suspect that most others will find it appropriate, and not the “tragedy” which some reviewers have deemed it. With this easy introduction to the work of Sada, many readers will undoubtedly look forward to reading another of his novels, his much more complex and intriguing

Though the novella is simple to understand, Sada has some remarkably subtle touches, making the reality of the sisters’ love for each other real in proportion to the jealousy of one and the triumph of the other. Their long interdependence has commanded their lives, and the fear of abandonment and hostility is real for both of them. As the action develops, the reader and the twins themselves soon conclude that the Gamals are neither the “saints” nor the “single pureness” which the narrator originally believed them to be. Their separate desires, dreams, and hopes for the future, forged as they are from their noticeably different personalities, surge forth under the stress of Oscar Segura’s courtship. The conclusion may surprise some, but I suspect that most others will find it appropriate, and not the “tragedy” which some reviewers have deemed it. With this easy introduction to the work of Sada, many readers will undoubtedly look forward to reading another of his novels, his much more complex and intriguing  In his newest novel, Simon Mawer continues the story of Marian Sutro, whose wartime exploits he introduced in

In his newest novel, Simon Mawer continues the story of Marian Sutro, whose wartime exploits he introduced in